Setting the Record Straight: ‘Custer’s Unsung Scouts’ by Bruce Brown

Arikara, Crow and Sioux scouts at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

From official Seventh Cavalry records and interviews with survivors.

THE STORY of the U.S. Army’s “wolves” — the Crow term for scouts — at the Little Bighorn is easily the most confused part of the whole tangled tragedy.

Going on two centuries after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, it’s still impossible to answer basic questions about the scouts who were with George A. Custer on June 25, 1876 — such as what were their names, how many were killed, and what were the identities of the dead.

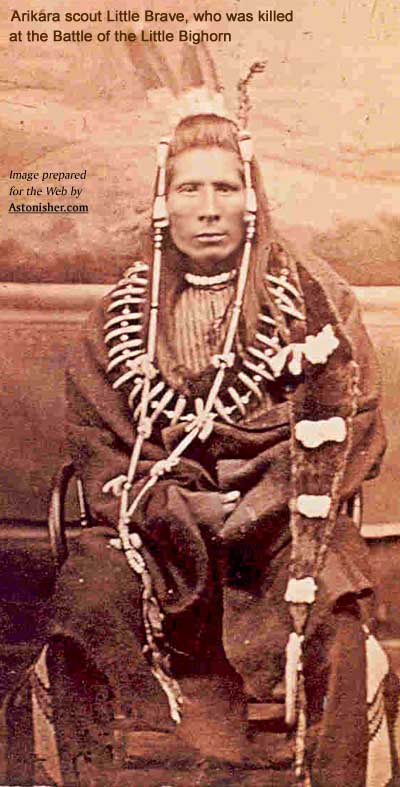

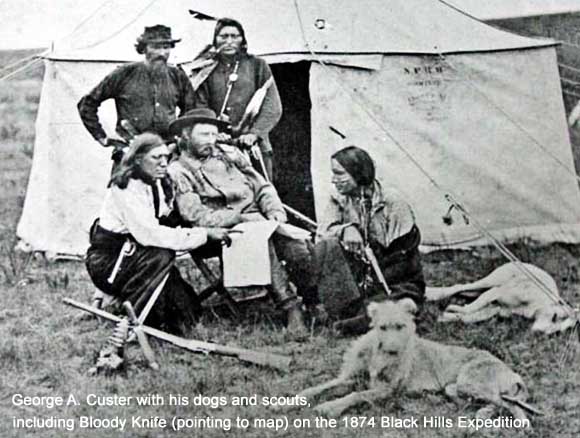

Today, the Accepted Consensus View of American Little Bighorn scholars holds that three Ree (or Arikara) scouts for the U.S. Army were killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn — Bloody Knife, (actually a half-Sioux / half-Arikara guide), Bobtailed Bull and Little Brave — although this number is not supported by either the eye-witness record or the confused, incomplete and contradictory Seventh Cavalry records.

On the Indian side, Horn Chips said Crazy Horse told him that five of the Seventh Cavalry’s Ree scouts were killed by the Sioux and Cheyenne at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The eye-witness record of the battle indicates that the truth is probably closer to what Crazy Horse said than the Americans. Eye-witness accounts by Sioux warriors Eagle Elk, Turning Hawk, White Cow Walking, Cheyenne warriors Wooden Leg, Brave Bear and Turkey Legs, and the pictographic history of Oglala Sioux by Amos Bad Heart Bull indicate that more than a half dozen unidentified U.S. Army scouts died with Custer.

Here are nine unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatalities reported in eye-witness accounts from Astonisher.com’s 100 Voices, the largest and most complete collection of eye-witness accounts of the Little Bighorn ever assembled:

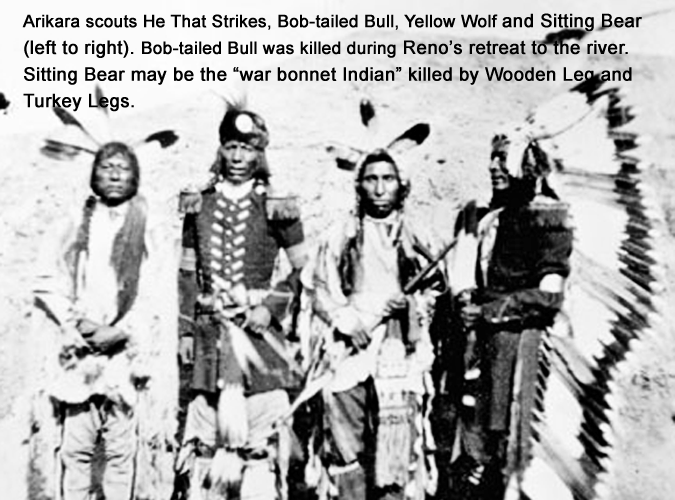

1) Cheyenne warriors Wooden Leg and Turkey Legs both described Cheyenne warrior Crooked Nose killing a “war bonnet Indian belonging with the soldiers” after a protracted chase through a slough in the timber along the river early in the Reno fight. Unfortunately, Seventh Cavalry records provide no information on this individual at all, and the conventional wisdom of Little Bighorn authors is equally unhelpful.

The Accepted Consensus View of the Little Bighorn holds that three Seventh Cavalry scouts were killed during the battle, but they are all known to have died elsewhere under different circumstances. Here are the details of Bloody Knife, Bobtailed Bull and Little Brave‘s deaths…

* According to both George Herendeen and Edward S. Godfrey, Bloody Knife (who was wearing a star spangled hankerchief Custer had given him, not a war bonnet) was killed standing at Reno‘s side near beginning of the fighting in a clearing in the timber by a sudden, unexpected fusilade from the trees.

* Bobtailed Bull (or Bob-Tailed Bull, Bobtail Bull, Bob-Tail Bull) was killed a few minutes later at the river in a mounted duel, probably with Cheyenne suicide warrior Little Whirlwind.

* Little Brave was wounded at the river and killed a little later on the east side of the river “behind a little sage brush knoll.” Here is Brave Bear’s story of counting coup on Little Brave.

So who was the “war bonnet Indian belonging with the soldiers” that Crooked Nose killed along the slough? There is a slight possibility that the “war bonnet Indian belonging with the soldiers” may have been Arikara scout Sitting Bear, based on a Montana Historical Society photo taken of the Arikara scouts before battle which shows Sitting Bear in an extravagant war bonnet. But at this point, no one knows. This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #1.

2) The Accepted Consensus View of Little Bighorn scholars is that Bobtailed Bull was the Ree scout Eagle Elk described the “Stripped Man” (High Horse?) grappling and then killing on the ground during Marcus Reno‘s frantic “charge” to the river, but actually this can’t be true because Bobtailed Bull was killed in the saddle — perhaps by the young Cheyenne suicide warrior Whirlwind — as evidenced by the blood all over the front of his saddle noted by Arikara scout Red Bear. So who did the “Stripped Man” kill? This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #2.

3-5) Besides, the Accepted Consensus View of the Battle is that Bobtailed Bull was also the scout killed by Turning Hawk, even though Turning Hawk clearly and specifically stated he killed a Sioux scout named Brush on the east side of the river. There is no one named Brush (Sioux or otherwise) on Varnum‘s Scout Roster, but there is an Arikara named Bush. Could this be the person Turning Hawk killed? Either way, the Stripped Man and Turning Hawk can’t have killed the same person in different encounters! Turning Hawk said he also killed two other Seventh Cavalry scouts — “one Sioux and one Crow” — earlier in the Reno fight. These are unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatalities #3, 4 and 5.

6) White Cow Walking, the son of Horned Horse, said he killed a “soldier scout” named Crow Flies High in the valley fight. There is no scout named Crow Flies High listed on any of the known scout rosters. This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #6.

7) Crazy Horse‘s brother-in-law, Brule Sioux warrior Red Feather, said he and Kicking Bear killed a Seventh Cavalry scout on the east side of the river. This fatality could be Arikara scout Little Brave, except for the fact that Red Feather described how he and Kicking Bear saw two scouts wearing white shirts and blue pants cross the river together and gave chase. The details of Red Feather and Kicking Bear‘s kill do not agree with the description by Arikara scout Red Bear of how he found Little Brave alone and wounded on the east bank of the river shortly before he was killed. This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #7.

8) There is a microscopically slight possibility that the “Hunkpapa who was with the soldiers“ killed by Sioux woman warrior Moving Robe could have been Isaiah Dorman, AKA Teat, who was also known to the Sioux as On Azinpi, (the black former slave who married a Lakota woman and was befriended by Hunkpapa Sioux chief Sitting Bull before betraying the Sioux) as the Accepted Consenus View of the Battle has it, but much more likely he was one of half dozen or more mercenary Sioux who were scouting and/or interpreting for Custer‘s Seventh Cavalry on June 25, 1876.

The Arikara Narrative states that four Sioux scouts acccompanied Custer‘s Arikara scouts, and gives their names as Ca-roo or Karu (Cards), Ma-tok-sha (Red Bear), Mach-pe-as-ka (White Cloud) and Pta-a-te (Whole Buffalo or Buffalo Body or Buffalo Ancestor), but only two of these names appear on Varnum‘s Seventh Cavalry Scout List, and one of them (Caroo or Cards), was supposedly discharged prior to the battle, according to the U.S. Army records cited by Walter Mason Camp, who stated that Caroo was also known as Bear Running In The Timber, even though Camp‘s own Scout List has Bear Running In The Timber as another Sioux mercenary named Matochun Way A Ga Mun. Meanwhile, Arikara scout Running Wolf testified that Caroo was still in the service of the American Army — specifically Gen. George Crook — immediately after the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

David Humphreys Miller gives the names of the four Sioux mercenaries as “White Cloud, Buffalo Ancestor, Red Bear (not to be confused with the Arikara scout of that name), and Caroo,” and said they were all “married to Arikara women.”

But actually there were more Sioux with Custer that day. In addition to Matochun Way A Ga Mun, Camp‘s Scout List mentions another Sioux scout, Bear Come Out (Mato Hinapa). Arikara scout Strikes Two also mentioned a Sioux scout named Watoksha. In Custer in ’76, Kenneth Hammer, wrote: “Watoksha, also spelled Watokshu by Camp, was a Dakota Sioux scout also known as Ring Cloud, Spotted Horn Cloud, and Round Wooden Cloud.” However, Walter Mason Camp‘s own Scout List in Custer in ’76 gives Round Wooden Cloud‘s Sioux name as Machpa Gachumga.

Walter S. Campbell mentions another Seventh Cavalry scout with a Sioux name, Buffalo Cloud, whom he says was a Ree who spoke Lakota. Campbell places Buffalo Cloud in the heat of the action during Reno‘s flight, when he killed two Cheyenne warriors, Swift Bear and White Eagle. There is, however, no further mention of Buffalo Cloud, or whether he survived the battle.

And Arikara scout Red Bear mentioned the presence of the “half-breed Dakota interpreter, E-esk,” who is on none of the scout lists. E-esk is sometimes identified as half-breed interpreter Billy Cross, but there is disagreement among primary sources on this point.

Was one of these Sioux mercenaries the “Hunkpapa who was with the soldiers” killed by Moving Robe? There is no way or knowing at this point, but there are certainly plenty of reasonable possibilities without having to turn a black man into a Hunkpapa. This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #8.

9) Finally, in his Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioiux, Amos Bad Heart Bull depicts his father, Bad Heart Bull, killing another unidentified Army scout. This is unidentified Seventh Cavalry scout fatality #9.

The tragicomic problem that the Accepted Consensus View of the Battle of the Little Bighorn faces here is that there are more dead bodies lying around in the eye-witness record of the battle than it has identities to cover them.

Because conventional American authors are all wedded to the peculiar, unsubstantiated notion that only three Indian mercenaries died with the Seventh Cavalry at the Little Bighorn, they are forced to play an endless game of “The Sheet’s Too Short” with the identities of the Indian dead, making Bobtailed Bull the scout killed by the “Stripped Man” until he’s needed to be the scout killed by Turning Hawk, etc.

Then there’s the amazing story of Chat-ka (see below). And who knows — there may even be more. But whatever their number, these unknown men gave their lives for America, where they remain unsung and unhonored to this day.

Somehow, over the last century and a half, an ungrateful America never found the time to identify all the Native Americans who died fighting for the United States on June 25, 1876.

* * *

BURIED IN the scout annals is one of the most poignant of all the Little Bighorn stories, that of the Sioux warrior Chat-ka, who also scouted for Custer and the Seventh Cavalry. Chat-ka was discharged from the U.S. Army in June 1876 and joined the huge encampment of free Sioux and Cheyenne Indians on the Little Bighorn shortly before the battle.

Whatever warning Chat-ka brought did little good, though, because Custer pushed all night on June 24 – 25, and threw his tired men and horses into battle immediately, which the Sioux and Cheyenne did not expect, for all their keen scouting intelligence and the Cheyenne decoy / scouts that Crazy Horse scrambled that morning when he learned from Fast Horn that Custer was at the Crow’s Nest at dawn.

When Custer attacked, Chat-ka fought for the free Sioux and Cheyenne against his former comrades in the Seventh Cavalry, and was killed. Arikara scout Young Hawk found Chat-ka‘s corpse afterwards in the abandoned Indian village:

“He had on a white shirt, the shoulders were painted green, and on his forehead, painted in red, was the sign of a secret society. In the middle of the camp they found a drum and on one side lying on a blanket was a row of dead Dakotas with their feet toward the drum… This drum was cut up and slashed.”

Chat-ka‘s name does not appear on any surviving Seventh Cavalry scout list. If Car-oo was actually present at the battle, as Arikara scout Strikes Two said, then Chat-ka may be another name for one of the Sioux scouts identified as Broken Penis, The Shield or Left Hand in Walter Mason Camp‘s notes, since these three Sioux scouts were likewise apparently discharged from the U.S. Army shortly before the battle. Another possibility is that Chat-ka was another name for Buffalo Cloud, mentioned by Walter S. Campbell.

Another point of confusion: W.A. Graham names the Ree scouts killed at the Little Bighorn as Bloody Knife (a guide, actually), Bobtailed Bull and Stab, but Stab apparently didn’t die in the battle. (Here are descriptions of Stab arriving safely at the Powder River on June 26 by Arikara scouts Strikes Two and Little Sioux.) Hardorff and most recent writers name the third dead Ree scout as Little Brave, but the name Little Brave isn’t even on Graham‘s list of Arikara scouts. You get the idea.

To try to shed some light on The Twisted Saga of the Unsung Seventh Cavalry Scouts, Astonisher.com offers the Seventh Cavalry Scout List of Arikara scout Boychief, plus the lists of two respected, early Little Bighorn scholars, Walter Mason Camp and W.A. Graham.

Click here for the complete ‘Custer’s Unsung Scouts’ by Bruce Brown…

BRUCE BROWN’S NOTES:

In addition to the Indian and half-breed scouts mentioned by Graham and Camp, there were also more. White scouts Lonesome Charley Reynolds and George Herendeen (the former was head scout, the later was assigned to the Seventh Cavalry by Custer‘s commanding officer, Gen. Alfred Terry), plus Fred Gerard, nominally an interpreter but actually a scout much of the time, and Isaiah Dorman, AKA Teat, the Black interpreter / scout. Reynolds and Dorman died at the Little Bighorn.

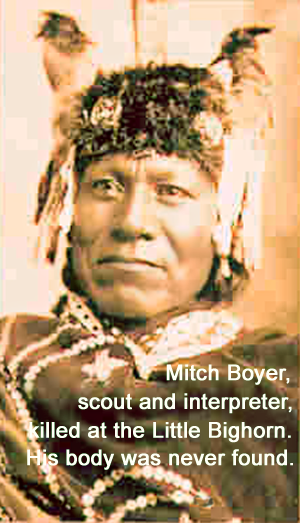

And notably, Mitch Boyer (or Bouyer), was also present, and also died on the battlefield. There is a marker for Boyer in the Deep Ravine on the battlefield, but this is in error. According to White Cow Bull‘s eye-witness account, Boyer was badly wounded at the very beginning of the Custer fight when Custer attempted charge across the river at Medicine Tail Coulee. His body was never found.

* * *

On the other side, here’s a synopsis of what the free Sioux and Cheyenne knew from their scouts about the Seventh Cavalry’s movements before the battle, and High Dog‘s description of Sioux and Cheyenne scouting: “how it is done.”

3 thoughts on “Setting the Record Straight: ‘Custer’s Unsung Scouts’ by Bruce Brown”

Comments are closed.

I’m really impressed along with your writing skills as smartly as with the structure for your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it your self? Either way stay up the excellent quality writing, it’s rare to look a great blog like this one nowadays.

I am part Ree scout, my family takes care of the 1st Ree scout cemetery in North Dakota, ask for Donnie (a real living Native American Green Beret scout) the caretaker of the cemetery it’s the most sacred Native American ground in America.

History of war is normally written by the victors but in this case the story line was written by the losers, the 7th Calvary had at least to me a lot of cover up in their accounts.

The accounts of the Indians is much more reasonable than the story of Custer making a brave last stand.

I go along with the accounts of White Cow Bull shooting a leader that just turned out to be Custer.

Custer being shot in the chest, knocked out of his saddle into the water causing the soldiers to dismount and try and recover Custer may explain why the confusion in the ranks.

Look up 100 Voices for the to me true information.