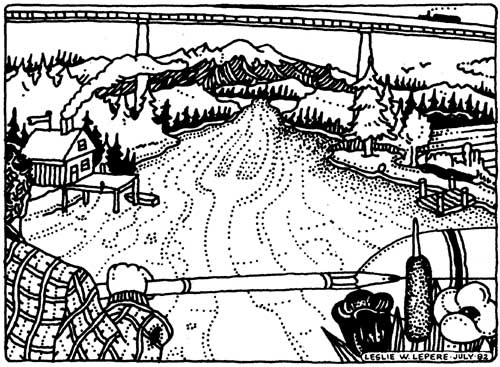

‘Skagit River Reverie’ by Bruce Brown

“Here time runs on the tides, the seasons and the salmon. A friend is someone who will bail your boat when you are stuck in town, and a funny stanza on ‘The Parable of the Three Sages Tasting Vinegar’ is worth more than a Volvo.”

OUR FIRST strokes scattered the reflection of the sun on the cliffs, and carried us out onto the still shadowy Swinomish Sough. It was only a few minutes after sunrise, but the town of LaConner was already stirring. A bearded man in rubber boots whistled an old Beatles song as he walked along one of the dilapidated cannery docks. Across the street, a man who had spent the night in the park emerged from the bushes with the box that contained his belongings. Nearby an elderly couple in a white Buick with British Columbia plates circled the block trying to find the LaConner Smelt Derby.

With a light north wind at our backs and the tide running the same way, we slipped down the Slough. My wife Lane, who sat in the forward seat of our two-person kayak, set a pace that quickly brought us out of the shadows into the morning sunlight. To the east the weedy edge of LaConner was disappearing into the sand dunes where the wrecked hulk of a Boeing 707 sat for many years, the sphinx of the Skagit. Shelter Bay, a sleek and extensive development built on land leased from the Swinomish Tribe, ran along the other side all the way to the head of the slough, where the cliffs rose again. As we glided through the rocky gates, Skagit Bay widened before us, with Goat Island a mile off in the mist to the west, McGlinn Island close at hand, and a jetty running between them. Although we couldn’t see it, we knew them was a small opening in the jetty known as the Fish Hole.

Our destination was through this hole and up the North Fork of the Skagit River. We hoped to find our friend, the poet Robert Sund, home at his place on Shit Creek (as some unknown Bohemian wryly and permanently defamed it), and along the way explore the small communities that dot the lower Skagit. Several of these — Sullivan Slough, Heartbreak Hotel and Siltable Slough — are only accessible by water, which gives them a privacy rare in modern times: no door-to-door salesmen, no garbage collection, no worry about WPPSS’s bills, no water from the tap, either hot or cold. Here time runs on the tides (you go upriver on-the flood, and come back down on the ebb), the seasons and the salmon, much as it did in the days before the white man came to this country. A friend is someone who will bail your boat when you are stuck in town, and a funny stanza on The Parable of the Three Sages Tasting Vinegar is worth more than a Volvo.

We were about 50 yards from the jetty when we first spotted the yellow highway sign that proved to be the marker for the Fish Hole. The tide was nearly all the way out, but there was just enough water left to whisk us through the 12-foot-wide gap between the boulders, which was like a little section of mountain stream set at tidewater. Too tight for any power or sail boat to navigate, the Fish Hole was left for the passage of salmon, not people; when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the long jetty sealing off the Slough for log storage. On the other side, we entered the North Fork of the Skagit, which carries something like two-thirds of the river’s flow in a channel a little less than a mile wide. In the old days before the jetty, the river was deep enough for gill netters to fish all the way across, but now it has silted in so much that constant attention is`required to avoid running aground even in a kayak.

From experience, we knew to track the deepest water by its color. Skagit green was what we wanted; blue and especially brown were to be avoided. The first of 14 blue herons rose from the flats on the north side of the river, beat its wings six or seven times, and then glided down across an inlet where some bleached structures and a ramshackle dock were tossed on the shore. On a hot Indian summer afternoon four years before, we had launched our kayak from this dock. There was a road in then, and a couple dozen men, women and children. swimming and sunbathing. While we assembled our boat, two women lounging on the dock engaged in a nude game of dunking for artifacts. One with long wavy blond hair came up with an unopened bottle of Labatt’s Beer. The other, who had a blue rose tattooed on her shoulder, pulled up a quite efficient looking hook-bladed. knife. Just as we were shoving off, Tom Robbins appeared in jeans, T-shirt and sunglasses, asking if anyone wanted to play volleyball.

We ran aground again and again that day, but this time we managed to snake our way through without a serious hitch. Ahead a single thread of smoke rose from a houseboat on Sullivan Slough, which follows a course exactly parallel to the Swinomish Slough for a good ways back into the Skagit Valley farmland. A rocky fronted island resembling a balding man’s pate lay immediately beyond. This half forested promontory forms both the upriver bank of Sullivan Slough, and on the other side, the downriver bank of Shit Creek. The tide was a rising force behind us now, but not so strong as the river in our faces. Leaning a little harder on the paddles in our steady rhythm, we rounded the rock and slipped into the mouth of Shit Creek, which is not a creek at all, but a sometime side channel of Sullivan Slough.

This narrow channel of still water wound to the north along the edge of a large grassy marsh. Jewels of ice glistened on the muddy bank, while a drift log (vine in the grass above was steaming. I always feel a sense of well-being on this limpid stream, for if ever there was a place you could stand to be stuck without a paddle, it is here. Robert, who is a poet, puts it in other terms. Speaking of his first encounter with the river communities of the lower Skagit, he told me: “it was like stumbling into something where the old Chinese poets might have been. You had this sudden intuition that they had nothing better than this. This was the true sense of wabi — you know, the Japanese Zen idea of wabi — where you don’t have much and you don’t lack anything either.”

It was a little after nine o’clock when Lane and I spotted Robert’s place rising out across the marsh on stilts. Originally built as a net shed by early salmon fishermen, the structure had deteriorated to the point where only two walls were left standing when Robert began to fix it up in 1973. Robert worked all that summer and, part of the next transforming it into a home. From the distance, the result looked like a cross between Norse and Oriental architecture, with a touch of prehistoric Swiss’ lake dweller thrown in.

Drawing closer, we could see the high pitched shake roof, mullioned windows and unpainted, weather-silvered siding. The structure was unusual, but it showed a fine eye for weight and texture. Eight feet below was a floating dock where a rowing dory and kayak were tied up. Next to it on its own pole was what appeared to be the only painted part of the whole scene, a birdhouse in the form of an ashram. We docked, scampered up the ladder of unevenly spaced rungs (there’s a poet for you), and knocked on the front door.

Opening, it revealed not Robert but a friend. He said Robert was in LaConner getting ready to go to San Francisco, and invited us in for some morning tea, a staple on the river. The place seemed the same as ever: a tiny L-shaped room with kitchen, living room, study and bedroom all crammed together so tightly that The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke could be reached from the brown rice jar, and nothing was more than an arm’s length from the elegant little cast iron stove. There was clutter everywhere, but also ingenious arrangement and an enchanting sense of space. Built for one person, this cabin was a poet’s high performance vehicle. Here you can find clarity through immersion in the natural world, literature and hard work. Here you could drink hot sake under the full moon and recite poetry until the couplets come home.

It is ironic considering Robert’s long residence on the Skagit, Shi Shi Beach and Elma that he is best known for his classic ode to the Palouse wheat harvest, Bunch Grass. This may change soon, however, for two new volumes of Robert’s poetry: are scheduled to be published by North Point Press in Berkeley, The Hides of the White Horses Shedding Rain and Ish River. Both of these collections draw heavily on the soggy feeling of the West Side, and Ish River in particular seems tied to his time on the Skagit and his love for the rivers that drain into Puget Sound. Anticipation over the appearance of these books is great among the people who have heard Robert read his poems over the last decade.

Leaving Robert’s with a tide table that his friend was kind enough to give us, Lane and I continued up the Skagit by way of Siltable Slough, a slow side channel of the main river lined with log booms. Several stilt houses were visible in the willows on both aides, including one trim place where a man was splitting firewood on the deck. Fishtown, which is the largest of the river communities, swung into view as we paddled, out of the slough into the main river again. Lying in the crook of a big bend in the river, this old-time water settlement has two parts. The first is a faded troupe of stilt houses and towers looming out of the trees. A network of boardwalk plankways running six or seven feet off the ground through tunnels in the alder and willow connects these places, most of which are fishermen’s sheds that have been converted into residences.

The structure known as the Temple is also located here. A simple old building with double doors that open directly over the river, this former net shed has served as a sort of community place of musing and music. Mandolins and autoharps mixed with the swallows that sweep in out of the open doors to feed their young, the insistent sucking of the river and the tide, and other elemental music: Robert once told me how Charlie Krafft, another river poet, had created his own instruments by hanging old crosscut and circular saws from the rafters. “When struck with a railroad spike, they would go booOooOooOoong, making; music through the laws of physics as they bounced up and down, They were terribly rusted — all crusted over with China red and lightning blue — but they made beautiful tones. Sometimes when Charlie played it was like hearing incredibly ancient melodies.”

As we paddled below it, the Temple was silent and closed as a heliotrope at night. Its weathered walls gave no indication of the art that has blossomed there during the long days of summer. Later in the year, though, when the weather warmed up and the sports salmon season began, it would again be the scene of impromptu concerts by the Asparagus Moonlight Chopstick Choir. Like Room 17 at the Nordic Inn in LaConner (where Mark Tobey stayed almost a half century ago, Guy Anderson’s old storefront down the street, Richard Gilke’s converted church near Stanwood, Tom Robbins’ small tree-shrouded house on the hill above LaConner and Robert Sund’s place on Shit Creek, the Temple at Fishtown is one of the wellsprings of the Skagit Valley arts scene. A sort of 20th century Shinto kami shrine, it has been a source of the Oriental flavor traditionally found in much Skagit Valley art.

The second part of Fishtown is located about 50 yards upriver at the base of a green hill. These houses had the look of old summer resort cabins, and more than one showed evidence of having been painted sometime during its existence. Cows were grazing on the side of the hill and smoke was wafting from the chimney of the farmhouse on top, but otherwise there was no movement. We drifted on the current as a part of the still life for a moment, and then pushed around the big bend, where the river ran under red rock cliffs. Stretching out our strokes in the pleasure of their easy, synchronous motion, we sped upriver into the Skagit Valley until we outran the tide and the river began to wear us down. At river mile four, we fought our way under the Browns Slough Road Bridge into a smooth stretch with Mount Baker floating in the sky ahead and a bald eagle circling around and around over the mountain’s glacial summit.

Turning back for LaConner, we made excellent time to Sullivan Slough, shot back through Fish Hole on the now reversed tide, and surfed under the high rainbow bridge into LaConner on the wake of passing yachts. Tying up at the La Conifer Tavern dock, we encountered Robert, who was in great form. His eyes twinkled behind his wire-rimmed glasses as he told us all the news. The Smelt Derby had been cancelled because of the cost of law enforcement, and then everyone came anyway.

Listening to him laugh over beer in the crowded tavern at sunset, I thought of a note he once sent to Hans Nelson at Fishtown: “even though I’m in Seattle now, I’m rowing my boat on the river.”

“Skagit River Reverie” by Bruce Brown and “North Fork Skagit” by Les Lepere originally appeared in the July 1988 issue of State Magazine.