‘Bad Bottled Water’ by Bruce Brown

Due diligence reveals why America drinks water from Coke & Pepsi…

I’VE TAKEN to loitering around the bottled water in supermarkets and convenience stores lately. Sad but true. Just me and a swelling throng of Americans — especially young Americans — buying bottled water.

I’m fascinated by these people because they think they are making a choice. It’s written on their faces as they stand in the quiet hiss of the air conditioning and consider a typical array of American consumer options: different brands, package sizes and prices.

But the truth is, no matter how long they stand there and study the matter, they’re going to end up making the same decision. If they don’t buy cheap generic water, most of these people end up purchasing bottled water from Coke, Pepsi or Nestle, whose brands include Dasani, Aqufina, Earth20, Arrowhead and others.

These products — sometimes dubbed “Aquasani” — are the highest priced domestic waters on the market, and also among the worst. Dasani and Aquafina, Coke and Pepsi’s big #1 brands, are known in the industry for their discernable after-taste when drunk at room temperature. And that’s not an industry secret either.

My 20-year old daughter Laurel, home from Santa Barbara, CA, where she’s going to college and drinking a lot of bottled water, told me she doesn’t like the taste of Aquafina — she made a face and fanned her mouth — but she drinks it anyway. She said her boyfriend Austin prefers high end Fiji Water, but he’ll drink Aquafina when he can’t get something better. “He won’t drink Dasani, though.”

Laurel and Austin aren’t alone. In 2004, Coke had to pull Dasani out of the UK market less than two months after its introduction because it was revealed that the Dasani that Coke was selling in England didn’t come from mountain glaciers or artesian springs, but rather out of the tap, according to the BBC. In other words, the Dasani sold in England was filtered tap water. And in 2016, Pirl reported the same was true of the world’s largest selling bottled water, Pepsi’s Aquafina.

And bad taste isn’t the only obstacle Dasani and Aquafina have to overcome in the marketplace. They both have to be hauled long distances, which increases their cost to market. Frequently there are far better and cheaper sources of water available locally. Here in Whatcom County, WA, for instance, there is a major source of sweet artesian spring water just five minutes drive from where I live, but there are no local bottled water brands on the supermarket or convenience store shelves.

So why do Americans drink Pepsi and Coke water products when they don’t really like them, and the basic mechanics of a free market economy say they shouldn’t have to? If there is any place where the local guy should have an inherent advantage over a distant competitor, American business dogma says it’s the bottled water business. In fact, bottled water comes very close to being what economists call a “pure market.” Since good water is pretty much good water — and competing products are virtually indistinguishable — the underlying economics of the marketplace should rule, inexorably tipping the scale in favor of the concern that can bring the best product to market the most economically.

A product as mediocre and over-priced as Dasani should have zero chance in this market. But in the brave new world of water, bottled water from a company in Plano, TX, sells a lot in the Pacific Northwest. Why aren’t there strong local products on the shelves of the neighborhood store, here and elsewhere around America? Seriously!

Well, as an executive at a Bellingham beverage distributing company said to me recently, “this is NOT a perfect free market system.” Or as the Merovingian put it in The Matrix Reloaded, “choice is an illusion perpetrated by those with power upon the powerless.”

* * *

HOW IMPERFECTLY the American bottled water business works became apparent to me recently when I did due diligence for a locally-owned company looking to open a bottled water business near Bellingham, WA, a delightful, rapidly growing West Coast city with notably bad drinking water.

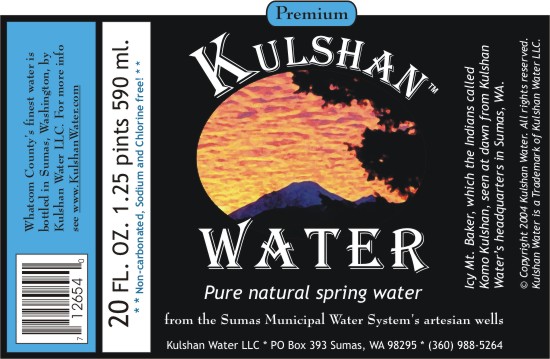

From the outset, almost everything about the Kulshan Water deal looked very promising. The local company had excellent, inexpensive water, closer to Belligham than any other source; it had the perfect name with a lot of proven local appeal; it had an eye-catching label and marketing plan; it had an eager distributor with real muscle in the Bellingham market. There were even lots of very hip co-promotion possibilities with the local company’s other outdoor sport ventures, which are considered a big plus these days in any bottled beverage’s promotional plan.

In the end, we had a mamouth, staggering checklist with “Yes” by every item but three:

1) Access to consumers — During due diligence I discovered that even with a reputable and enthusiastic distributor, a local bottled water could only hope to get on the shelves in maybe 20 percent of the local outlets that sell bottled water. The reason for this is two-fold.

In many convenience stores — where Coke and Pepsi are very strong — The Big Two lock out all water competition with exclusive contracts. Even the local Nooksack Valley High School here has an exclusive contract with Coke for all its beverages. These deals are classic examples of illegal restraint of trade through tying contracts between buyers and sellers and are defined as illegal per se by the Sherman Anti-trust Act. But don’t hold your breath for the corporation-controlled American government to enforce federal law. This week, President George W. Bush was too busy signing into law an additional $138 billion in tax cuts for our corporate masters.

Meanwhile, in supermarkets — the other big retail arena for bottled water — “slotting fees” imposed by the stores frequently prevent superior local products from ever getting on the shelves. According to distributors, it costs tens of thousands of dollars in slotting fees to get an unknown, untried product into a regional supermarket chain. Slotting fees are probably illegal too, since they amount to extortion, with the stores shaking down their suppliers for a bribe as a condition of doing business, but again, don’t hold your breath for justice in the “free market economy.” It’s entertaining to think what would happen if someone like New York State Attorney General Elliot Spitzer was put in charge of enforcing federal anti-trust laws, but the fact is the middlemen and the multi-national corporations rule.

2) Retail split — Another indication of the middlemen’s power in the American bottled water business is the split — or share — the bottler, distributor and store each take of the final retail price. Here’s how it works. Of that $1.19 you paid for a 20 fl. oz. bottled of water at the C-store or supermarket, the bottler gets around 29 cents, the distributor gets around 38 cents, and the store gets 52 cents. That’s roughly 25 percent for the manufacturer, and 75 percent for the middlemen. Suffice it to say that it is very difficult to make as profit in ANY business where you only get 25 percent of the retail price of your product.

3) Price structure — The bottled water market is in fact growing rapidly, as all the news stories keep babbling, but production capacity has grown rapidly too, and right now bottled water prices are very soft. Those hip young consumers in the bottled water department see deep discounts all over the shelf these days. I recently saw Aquasani at $2.50 for a six pack of 20 fl oz bottles, which amounts to 40 cents a bottle and is not just below not the store’s cost, but quite likely below Aquafina’s cost of production, transportation, promotion, etc.

Why is Aquasani, excuse me Aquafina, doing this? Well actually, it’s being done to them. Bottled water prices are under assault all across the board from generic or house brand waters, which are exempt from the slotting fees since the supermarkets don’t charge themselves slotting fees. Here in the Pacific Northwest, a great deal of generic water production is being cranked out by big regional bottled water operators like Advanced H2O (formerly Cascade Clear) who bet wrong on large investments in high capacity equipment, and now must do low margin job-work for the supermarket chains to keep their production lines fully operational.

Advanced H2O does this even though it means driving down bottled water prices and throwing itself into the high volume, low margin pool with guess who… Coke and Pepsi. Oh oh! This summer when I talked to Bob Abramowitz, CEO of Advanced H2O, he sounded scared, and he should. He’s in a position roughly akin to big regional breweries like Rainier Beer and Olympia Beer in the 1980s, just before they grew themselves to death and their carcasses were picked clean by the big national beers and the little micro-breweries.

Clearly a shakeout is in progress in the bottled water business. But what about when it’s over? Will bottled water prices rebound then? I asked several beverage industry insiders this question, and their reply was pretty much, “look at history. There used to be a zillion soft drink companies. Now there’s only two. And what happened to prices? They’re incredibly low. Bottled water prices won’t be coming up any time soon.”

* * *

SO HERE’S the deal. We’ve got this truly amazing, wonderful who-ha product that people absolutely have to have — they literally can’t live without it — and the only problem is that we can’t get into three quarters of the local stores and we have to give away three quarters of the retail price to the middlemen. Oh yea, prices are soft. Expect them to hover around the cost of production for a generation or two.

Would you place a big bet on this sort of a prospect? I wouldn’t, and neither would the investors in Kulshan Water. Score another victory for Coke, Pepsi, and the Merovingian.

Originally posted January 2005.