From ‘100 Voices’ – White Cow Bull’s Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

An Oglala Sioux’s eye-witness account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

This is an excerpt from Bruce Brown’s revolutionary collection of eye-witness accounts of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 100 Voices from the Little Bighorn, the largest and most complete collection of eye-witness accounts of the battle ever assembled.

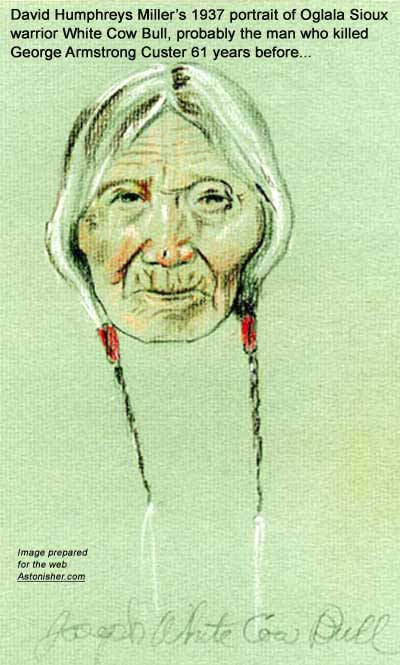

White Cow Bull’s story is from a battlefield interview with David Humphreys Miller in 1937.

* * *

THE OLD MAN sat cross-legged in the Montana sun, posing for me with his gaunt shoulders draped in an ancient trade-cloth blanket, gnarled fingers clutching a cottonwood cane. It was hard to imagine that his scraggy hands had once been dexterous with firearms, or that his watery eyes, with bluish, washed-out irises, had been among the keenest of any warrior’s who had fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

We were camped that August day in 1938 at the Crow Fair. His name was Joseph White Cow Bull. An Oglala Sioux from Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, he had come to have a last look at the battlefield before he died.

His name seemed somewhat anomalous in combining the bovine sexes. It made better sense in Sioux than it did in English. Ptebloka Ska indicated a male of the white man’s semi-domesticated longhorn cattle, which some interpreter, lacking fluency in English, had evidently mistranslated. White Cow Bull, I learned, had earned the name at age fourteen by shooting a stray longhorn bull with a single arrow.

My first portrait sketch of him completed, I loaded the old man in my car and headed south out of camp on U.S. Highway 87, by-passing the entrance to Custer Battlefield and National Cemetery so he could first see the site of the great Indian village where he had camped sixty-two years earlier. I realized that time and cultivation by the semi-agricultural Crow must have caused considerable changes in the look of the land. White Cow Bull nonetheless soon managed to point out where the wide ramp circles, each a half mile in diameter, had sprawled along the Little Bighorn River.

Spreading his hands to indicate a large circle, he said:

The Shahiyela [Cheyenne] camp was farthest north. We Oglala were camped just southeast of them, with the Brule in a smaller circle next to us. Next were the Sans Arc, then the Miniconjou, the Blackfoot Sioux, and farthest south next to the river were the Hunkpapa. I was twenty-eight years old that summer.

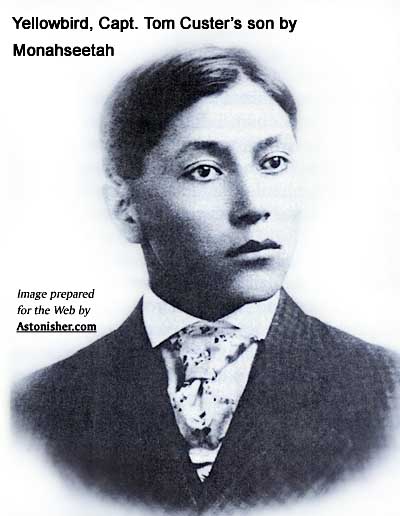

While we were together in this village, I spent most of my time with the Shahiyela since I knew their tongue and their ways almost as well as my own. In all those years I had never taken a wife, although I had had many women. One woman I wanted was a pretty young Shahiyela named Monahseetah [Mona Setah], or Meotxi as I called her. She was in her middle twenties but had never married any man of her tribe. Some of my Shahiyela friends said she was from the southern branch of their tribe, just visiting up north, and they said no Shahiyela could marry her because she had a seven-year-old son born out of wedlock and that tribal law forbade her getting married. They said the boy’s father had been a white soldier chief named Long Hair [George A. Custer, or more probably, his younger brother, Capt. Thomas Custer, sarcastically called Little Hair by the Sioux]; he had killed her father, Chief Black Kettle, in a battle in the south [Washita Massacre] eight winters before, they said, and captured her. He had told her he wanted to make her his second wife, and so he had her. But after while his first wife, a white woman, found her out and made him let her go.

“Was this boy still with her here?” I asked him.

I saw him often around the Shahiyela camp. He was named Yellow Bird [sometimes Yellowbird or Yellowtail] and he had light streaks in his hair. He was always with his mother in the daytime, so I would have to wait until night to try to talk to her alone. She knew I wanted to walk with her under a courting blanket and make her my wile. But she would only talk with me through the tepee cover and never came outside.

White Cow Bull sat silent a few minutes, musing on the past, I suppose, and remembering the Cheyenne girl Long Hair Custer had dishonored in the eyes of her people. Later interviews corroborated the old Oglala’s statement that Monahseetah and Yellow Bird had been in the Little Bighorn camp at the time of the fight, many of my Cheyenne informants insisting that their strict moral code, more rigid than that of the Sioux, imposed restrictions on their relationships with fallen women. I was already familiar with various accounts of Custer s winter campaign against the Southern Cheyenne in 1868, in several of which Monahseetah is mentioned as having served Custer as an interpreter — although she apparently then spoke no English! [Note: Here is Southern Cheyenne warrior Brave Bear‘s comment on Monaseetah.]

“Tell me about the battle with Long Hair,” I said.

That morning many of the Oglalas were sleeping late. The night before, we held a scalp dance to celebrate the victory over Gray Fox [General Crook] on the Rosebud a week before. I woke up hungry and went to a nearby tepee to ask an old woman for food. As I ate, she said:

“Today attackers are coming.”

“How do you know, Grandmother?” I asked her, but she would say nothing more about it.

After I finished eating I caught my best pony, an iron-gray gelding, and rode over to the Cheyenne camp circle. I looked all over for Meotzi and finally saw her carrying firewood up from the river. The boy was with her, so I just smiled and said nothing. I rode on to visit with my Shahiyela friend Roan Bear. He was a Fox warrior, belonging to one of that tribe’s soldier societies, and was on guard duty that morning. He was stationed by the Shahiyela medicine tepee in which the tribe kept their Sacred Buffalo Head. We settled down to telling each other some of our brave deeds in the past. The morning went by quickly, for an Elk warrior named Bobtail Horse joined us to tell us stories about his chief, Dull Knife, who was not there that day.

The first we knew of any attack was after midday, when we saw dust and heard shooting way to the south near the Hunkpapa camp circle.

Just then an Oglala came riding into the circle at a gallop.

“Soldiers are coming!” he shouted in Sioux. “Many white men are attacking!”

I put this into a shout of Shahiyela words so they would know. I saw the Shahiyela chief, Two Moon, run into camp from the river, leading three or four horses. He hurried toward his tepee, yelling:

“Natskaveho! White soldiers are coming! Everybody run for your horses!”

“Hay-ay! Hay-ay!” The Shahiyela warriors shouted their war cry, waiting in a big band for Two Moon to lead them into battle.

“Warriors, don’t run away if the soldiers charge you,” he told them. “Stand and fight them. Watch me. I’ll stand even if I am sure to be killed!”

It was a brave-up talk to make them strong in their fight. Two Moon led them out at a gallop…

After Two Moon‘s band left to fight Major Reno, a new threat developed from Custer’s detachment advancing down Medicine Tail coulee toward the river and the Cheyenne camp.

“They’re coming this way!” Bobtail Horse (or Bobtailed Horse) shouted. “Across the ford! We must stop them!”

We saw the soldiers in the coulee were getting closer and closer to the ford, so we trotted out to meet them. An old Shahiyela named Mad Wolf, riding a rack-of-bones horse, tried to stop us, saying:

“My sons, do not charge the soldiers. There are too many. Wait until our brothers come back to help!”

He rode along with us a way, whining about how such a small war party would have no chance against a whole army. Finally Bobtail Horse told him:

“Uncle, only Earth and the Heavens last long. If we four can stop the soldiers from capturing our camp, our lives will be well spent.”

The Sans Arc and Miniconjou camp circles were back from the ford. We found a low ridge along here and slid off our ponies to take whatever cover we could find. For the first time I saw five Sioux warriors racing down the coulee ahead of the soldiers. They were coming fast and dodging bullets the soldiers were firing at them. Then Bobtail Horse pointed to that bluff beside the ford. On top were three Indians that looked like Crows from their hair style and dress. [Note: the “three Indians that looked like Crows” were White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead and Hairy Moccasin. Here are Goes Ahead and Hairy Moccasin‘s description of the exact same moment in the battle.] Bobtail Horse said:

“They are our enemies, guiding the soldiers here.”

He fired his muzzleloader at them, then squatted behind the ridge to reload. I fired at them too, for I saw they were shooting at the five Sioux warriors, who were now splashing across the ford at a dead run. [Note: the “five Sioux warriors” may be a reference to the decoy / scouts that Crazy Horse scrambled when he learned from Fast Horn that Custer‘s troops were approaching on the morning of June 25, 1876. Foolish Elk described the exact same scene — with Custer‘s men coming in hot pursuit of a handful of Indians — but he said the decoys were Cheyenne.] My rifle was a repeater, so I kept firing at the Crows until these Sioux were safely on our side of the river. They had no guns, just lances and bows and arrows. But they got off their ponies and joined us behind the ridge. Just then I saw a Shahiyela named White Shield, armed with bow and arrows, come riding downriver. He was alone, but we were glad to have another fighting man with us. That made ten of us to defend the ford.

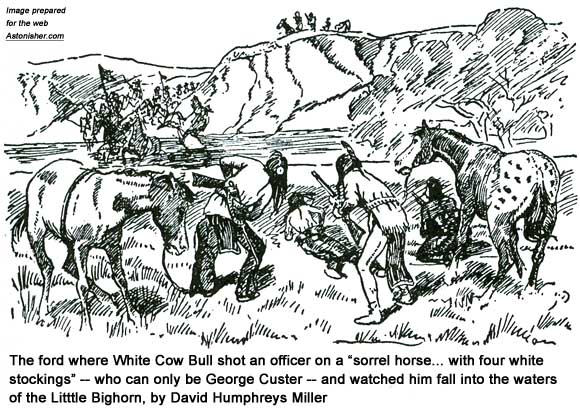

I looked across the ford and saw that the soldiers had stopped at the edge of the river. [Note: this agrees with Peter Thompson, who said Custer briefly halted his men at the ford while he rode upriver alone about 1,000 feet, either to scout a better place to cross or to rape the Sioux squaw Curley had waiting there.] I had never seen white soldiers before, so I remember thinking how pink and hairy they looked. One white man had little hairs on his face [a mustache] and was wearing a big hat and a buckskin jacket. He was riding a fine looking big horse, a sorrel with a blazed face and four white stockings. [Note: Although there were several officers in buckskin that day, Custer was the only one on a sorel horse with four white socks. The one detail that doesn’t agree with Peter Thompson’s account is that Thompson said Custer had taken his jacket off.] On one side of him was a soldier carrying a flag and riding a gray horse, and on the other was a small man on a dark horse. This small man didn’t look much like a white man to me, so I gave the man in the buckskin jacket my attention. [Note: According to Pretty Shield, the “small dark man” was Mitch Bouyer, head of scouts.] He was looking straight at us across the river. Bobtail Horse told us all to stay hidden so this man couldn’t see how few of us there really were.

The man in the buckskin jacket seemed to be the leader of these soldiers, for he shouted something and they all came charging at us across the ford. Bobtail Horse fired first, and I saw a soldier on a gray horse (not the flag carrier) fall out of his saddle into the water. The other soldiers were shooting at us now. The man who seemed to be the soldier chief was firing his heavy rifle fast. I aimed my repeater at him and fired. I saw him fall out of his saddle and hit the water. [Note: Seventh Cavalry scout Curley described seeing the same incident, and Pretty Shield confirmed that Custer was shot out of the saddle at the very outset of the Custer fight. See Who Killed Custer – The Eye-witness Answer for more info.]

Shooting that man stopped the soldiers from charging on. They all reined up their horses and gathered around where he had fallen. I fired again, aiming this time at the soldier with the flag. I saw him go down as another soldier grabbed the flag out of his hands. By this time the air was getting thick with gunsmoke and it was hard to see just what happened. The soldiers were firing again and again, so we were kept busy dodging bullets that kicked up dust all around. When it cleared a little, I saw the soldiers do a strange thing. Some of them got off their horses in the ford and seemed to be dragging something out of the water, while other soldiers still on horseback kept shooting at us.

Suddenly we heard war cries behind us. I looked back and saw hundreds of Lakotas [Sioux) and Shahiyela warriors charging toward us. They must have driven away those other soldiers who had attacked the Hunkpapa camp circle and now were racing to help us drive off these attackers. The soldiers must have seen them too, for they fell back to the far bank of the river, and those still on horseback got off to fight on foot. As warriors rode up to join us at the ridge a big cry went up.

“Hoka hey!” the Lakotas were shouting. “They are going!”

I saw this was true. The soldiers were running back up the coulee and swarming out over the higher ground to the north. Bobtail Horse ran to his pony, shouting to us as we caught our ponies.

“Come on! They are running! Hurry!”

He and I led the massed warriors across the ford, for the others knew we had stood bravely to protect the village and willingly followed us.

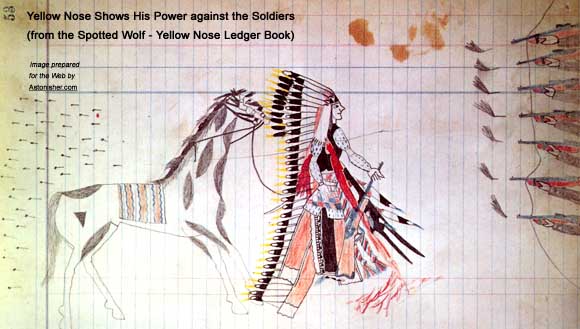

Another warrior named Yellow Nose, a Sapawicasa [Ute] who had been captured as a boy by the Shahiyela and had grown up with them, was very brave that day. After we chased the soldiers back from the ford, he galloped out in front of us and got very close to them, then raced back to safety.

I kept riding with the Shahiyelas, still hoping that some of them might tell Meotzi later about my courage. We massed for another charge. The Shahiyela chief, Comes-in-Sight, and a warrior named Contrary Belly [Contrary Big Belly] led us that time. The soldiers’ horses were so frightened by all the noise we made that they began to bolt in all directions. The soldiers held their fire while they tried to catch their horses. Just then Yellow Nose rushed in again and grabbed a small flag [guidon] from where the soldiers had stuck it in the ground. He carried it off and counted coup [struck blows] on a soldier with its sharp end. He was proving his courage more by counting that coup than if he had killed the soldier.

Now I saw the soldiers were split into two bands, most of them on foot and shooting as they fell back to higher ground, so we made no more mounted charges. I found cover and began shooting at the soldiers. I was a good shot and had one of the few repeating rifles carried by any of our warriors. It was up to me to use it the best way I could. I kept firing at the two bands of soldiers first at one, then at the other. It was hard to see through the smoke and dust, but I saw five soldiers go down when I shot at them.

Once in a while some warrior showed his courage by making a charge all by himself. I saw one Shahiyela, wearing a spotted war bonnet and a spotted robe of mountain-lion skins, ride out alone.

“He’s charging!” someone shouted.

He raced up to the long ridge where the soldiers of one band were making a defense standing there holding their horses and keeping up a steady fire. This Shahiyela charged in almost close enough to touch some of the soldiers and rode around in circles in front of them with bullets kicking up dust all around him. He came galloping back, and we all cheered him.

“Ah! Ah!” he said, meaning “yes” in Shahiyela.

Then he unfastened his belt and opened his robe and shook many spent bullets out on the ground…

The old man grinned at the memory of such courage.

It was a day of bravery — even for our soldier enemies. They all fought well and died in courage, except for one soldier on a sorrel horse. He broke away from the others and started riding off down the ridge. Two Shahiyelas and a Lakota chased after him, shooting at him as they rode. But the soldier’s horse was fast and they couldn’t catch him. I saw him yank out his revolver and thought he was going to shoot back at these warriors. Instead he put the revolver to his head, pulled the trigger, and fell dead.

This may have been 2nd Lieutenant Henry M. Harrington, C. Company, whose body was never identified. [Note: It is remotely possible that this suicide could also have been Custer himself. For more info on American suicides, see Who Killed Custer — The Eye-witness Answer.]

In a little while all my bullets were gone. But by that time the soldiers lay still. We had killed them all. The battle was over. Soon we were shouting victory yells. When the women and children heard us, they came out on the ridge to strip the bodies and catch some of the big horses the soldiers had ridden. Some women had lost husbands or brothers or sons in the fight, so they butchered the soldiers’ bodies to show their grief and anger.

I began looking for bullets and weapons in the piles of dead bodies. Near the top of the ridge I saw a naked body and turned it over. The face had little hairs on it and looked like the white man who had worn the buckskin jacket and had lired at me across the ford — the same one I had shot off his horse. I remembered how close some of his bullets had come, so I thought I would take the medicine of his trigger finger to make me an even better shot. Taking out my knile. I began to cut off that finger.

Just then I heard a woman’s voice behind me. I turned to see Meotzi and Yellow Bird and an older Shahiyela woman standing there. The older woman pointed to the while man’s body, saying:

“He is our relative.”

Then she signed for me to go away. I looked at Meotxi then and smiled, but she didn’t smile back at me, so I wondered if she thought it was wrong for a warrior to be cutting on an enemy’s body. I decided she wouldn’t be as proud of me if I cut off the white man’s finger, and moved away. Pretending to be busy looking for bullets, I glanced back. Meotxi was looking down at the body while the older woman poked her sewing awl deep into each of the white man’s ears. I heard her say:

“So Long Hair will hear better in the Spirit Land.”

[Note: Cheyenne youth Dives Backward witnessed this scene — a warrior trying to cut a finger off a dead American who was driven away by two grieving squaws, one Monaseetah and one an old woman with an awl.]

That was the first I knew that Long Hair was the soldier chief we had been fighting and the white man I had shot at the ford…

The tribes had split up after their victory at Little Bighorn. White Cow Bull never saw Meotzi again after that summer. Perhaps because of her, he never took a wife. After that day in Montana I saw the old man several times at Charlie Thunder Bull‘s cabin near Oglala, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, making three portraits of him before his death in 1942.

From “Echoes of the Little Bighorn” by David Humphreys Miller, American Heritage, June 1971, an excerpt from Custer’s Fall: The Indian Side of the Story by David Humphreys Miller, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 1957.

* * *

BRUCE BROWN’S NOTES:

THIS EYE-WITNESS account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn by Sioux warrior White Cow Bull is one of the three great Lost Texts — or perhaps I should say, Ignored Texts — of the Little Bighorn eye-witness canon (the others are the accounts of Peter Thompson and Pretty Shield).

From White Cow Bull we get three crucial parts of the Little Bighorn story.

First is the relationship between the Custer brothers (George Custer and his younger brother, Thomas) and their Southern Cheyenne prisoner-of-war concubine, Monaseetah, and her illegitimate half-white son, Yellowtail (also described by Cheyenne warriors Brave Bear, Dives Backward, Rising Sun, Little Chief and Brave Wolf, but pretty much ignored by American historians, although Jeffry D. Wert does mention it in Custer: The Controversial Life of George Armstrong Custer).

Second is the way Monaseetah stopped White Cow Bull from mutilating George Custer’s corpse (ditto).

Third is the most important (and therefore the most ignored) part of White Cow Bull‘s story: his crucial eye-witness description of how he shot an officer on a “sorrel horse with… four white stockings” — who can only be Custer — at the outset of the Custer fight when the “Gray Horse Company” attempted to ford the river at Medicine Tail Coulee and attack the huge Sioux and Cheyenne village.

ALL THE MAJOR points of White Cow Bull‘s story are supported by other survivors’ accounts (witnesses are in parenthesis, with links to supporting portions of their eye-witness accounts of the battle)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer‘s men charged down Medicine Tail Coulee to the banks of the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: White Man Runs Him, Curley, Pretty Shield, Bobtailed Horse, White Shield, Sitting Bull, Horned Horse, He Dog, Foolish Elk, Peter Thompson, John Martin, Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant)…

- White Cow Bull said three Crow scouts rode to the edge of the bluff above the river and fired down at them (witnessed by Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men were hotly pursuing a small band of Indians when they reached the river (witnessed by: Foolish Elk, George Bird Grinnell)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men encountered Indian fire from the other side of the river when they reached the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: Curley, Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant, White Shield)

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men paused on the far side of the river when they reached the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: Peter Thompson, White Shield)…

- White Cow Bull said after pausing the Americans charged across the Little Bighorn River to attack the Indian village on the other side (witnessed by Curley, Pretty Shield, Horned Horse, Elk Head, Seven Anonymous Hostiles

- White Cow Bull said the ford where Custer tried to cross the Little Bighorn was very thinly defended by the Sioux and Cheyenne (witnessed by: Bobtailed Horse, White Shield, He Dog, Wooden Leg, George Bird Grinnell)…

- White Cow Bull said he was one of the few warriors there when Custer charged into the river and the Indians opened fire (witnessed by: Bobtailed Horse)…

- White Cow Bull said that when the Americans tried to charge across the river at Medicine Tail Coulee, Custer rode at the head of the attack formation with the flag bearer and a “small man on a dark horse,” probably half-Sioux interpreter/scout Mitch Bouyer (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)…

- White Cow Bull said a couple Seventh Cavalry troopers were shot out of the saddle and fell in the Little Bighorn before Custer‘s men could get across the river (witnessed by: Curley, Horned Horse, Pretty Shield, Soldier Wolf, Elk Head, Thomas LaForge, plus Sage, Hollow Horn Eagle and Brave Bird reported wounded American soldiers at the river after the battle, including Mitch Bouyer, the half-Sioux interpreter/scout whom Pretty Shield said rode at Custer’s side)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer — the officer on the “sorrel horse with… four white stockings” — was one of those shot while crossing the Little Bighorn River (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer “fell in the water” of the Little Bighorn River (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)…

- White Cow Bull said Custer‘s charge at Medicine Tail Coulee was suddenly stopped and repulsed mid-river by the Cheyenne and Sioux defenders (witnessed by: Curley, George Glenn, Jacob Adams)…

Taken together, there is far more eye-witness corroboration and support for White Cow Bull‘s story than any of the other possible Custer kill stories in the eye-witness record of the battle. So White Cow Bull‘s story is not only the first and best of the possible Custer kill stories, it is also the best supported.

In fact, the only point of difficulty with White Cow Bull‘s story involves a couple small details; e.g., both Peter Thompson and Soldier said Custer had taken off his buckskin jacket and was riding in his shirt sleeves, while White Cow Bull said the officer he shot was wearing a buckskin jacket.

But who knows? Thompson and Soldier‘s observations were made earlier, and maybe Custer put his jacket back on for the attack. Either way, Custer was the only Seventh Cavalry officer on a sorrel horse with four white socks.

SO WHITE COW BULL‘s first account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn provides the eye-witness answer to the seemingly endless question — who killed George Armstrong Custer? See Who Killed Custer – The Eye-Witness Answer for more info. White Cow Bull‘s brief second account deals with the Siege of the Greasy Grass the day after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, when he shot the heel off the boot of an American soldier, probably Frederick Benteen or William Slaper.

Based on these two accounts — both supported by many other eye-witness accounts — you could argue that White Cow Bull was the most important warrior at the Battle of the Little Bighorn for two shots he fired, one of which he hit (Custer) and one of which he barely missed (Benteen), for the outcome of those two shots decided first the fate of Custer and his men, and subsequently the fate of Benteen and Reno and their men as well.

Regarding Custer‘s attempt to charge across the Little Bighorn and attack the Indian village on June 25, 1876, David Humphreys Miller wrote: “The fight at the ford was described to me by White Cow Bull and Bobtail Horse [AKA Bobtailed Horse], both of whom lived to be quite old. Custer‘s fall at mid-river was witnessed simultaneously by White Cow Bull and the three Crow scouts, although White Cow Bull did not know Custer‘s identity at the time. The account of the Crows was passed on to me by Pretty Shield, widow of Goes Ahead, with whom I had my first interview in 1940 when she was almost eighty-two years of age.”

Here is further commentary by David Humphreys Miller on “Who Killed Custer.”

* * *

According to his great grand daughter, Shirlee Stone, Yellowbird was later known as John Yellowbird Steele and was the proprietor a store in Porcupine, SD, called Yellowbird’s Store, which still exists. “He lived long,” she said, “and had success.”

Here is Brave Bear‘s commentary on Custer, Monaseetah and Yellow Bird, and here is another recollection of Monaseetah by Dives Backward, Rising Sun, Little Chief, and Black Wolf.

Regarding Yellow Bird‘s parentage, the case for his father being Capt. Thomas Custer rather than his illustrious brother, Gen. George A. Custer, rests on the assumption that the gonorrhea that George A. purportedly contracted while at West Point left him sterile and therefore incapable of fathering child. “He was shooting blanks,” cackled one old soldier.

* * *

Although not born into the Teton Sioux, David Humphreys Miller was adopted late in life by both Iron Hail and One Bull, and like the other Sioux, Cheyenne and Crow chroniclers in 100 Voices (Ohiyesa, John Stands In Timber, William Bordeaux, Pretty Shield, Bird Horse, George Bird Grinnell), he had unique access to important particpants in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, some of whom left no other record, such as White Cow Bull and Drags The Rope.

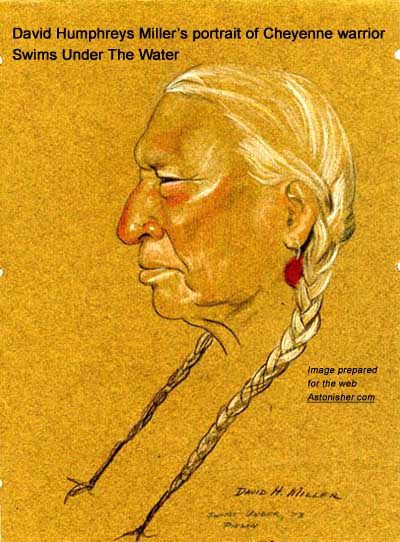

Miller frequenlty made pastel sketches of the Sioux survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn whom he interviewed. Some of Miller‘s portraits are exceptionally fine evocations of the historic personalities in their own right, such as his portraits of Lazy White Bull and Old Eagle and Black Elk late in life.

Click here for information of David Humphreys Miller’s sources among the Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Arikara and Apapaho.

–– Bruce Brown