Setting the Record Straight: ‘Mysteries of the Little Bighorn’ by Bruce Brown

THE BATTLE of the Little Bighorn sometimes seems like a Sea of Mysteries — and like the sea, it doesn’t give up its own easily.

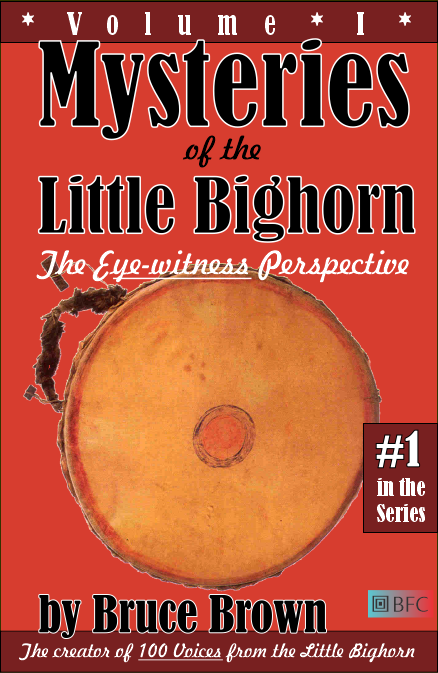

This is an excerpt from the five books Bruce Brown has written about mysteries of the Little Bighorn, all based on his seminal collection of eye-witness accounts of the battle, 100 Voices from the Little Bighorn.

These books are Mysteries of the Little Bighorn, Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4 and 50 Mysteries of the Little Bighorn – SOLVED!, all available on Amazon Kindle.

* * *

Q: Were there any white men among the Sioux and Cheyenne at the Battle of the Little Bighorn?

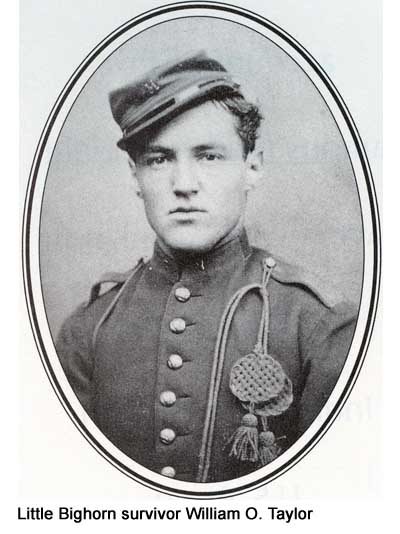

A: This is a question that first arose during the battle because Americans like Peter Thompson, John Ryan, William O. Taylor and an anonymous wounded survivor heard bugle calls coming from the Indian side.

Kill Eagle and John Stands In Timber said the buglers were Indians, and they probably were, but the question of whether one or more white men were on the Indians’ side on June 25, 1876 remains because of several comments in the contradictory eye-witness record.

Asked directly in September 1876 if there was a white among the Indians that day, Blackfeet Sioux war chief Kill Eagle replied, “There were no white men in the fight or on the field. One who had been with them went to Standing Rock Agency.” Quized again one month later if there was a “Spaniard” with the Indians, Kill Eagle said, “There was once a white man in camp, but he went to Spotted Tail’s [Agency] before the fight.”

Oglala Sioux war chief He Dog said he “did not see any white man among Sioux.” But then He Dog added significantly, “In my camp there was a Canadian half breed who spoke very good English as well as Sioux.” From He Dog‘s testimony, it appears that this individual was present on June 25, 1876.

Unreconstituted Confederate mercenary Frank Huston said, “I was a squaw man, yes; but I was not present at the Little Big Horn. I was 50 miles away headed thereto. But O — how I would have liked to have been there! Yet as a matter of fact, there were white men there; not with the Sioux, but with other nations present. Put yourself in their place. Would you, then or now, acknowledge it?” Huston provided no details to support his assertion.

The main eye-witness evidence that there may have been one or more white man fighting on the Indian side at the Battle of the Little Bighorn comes from the accounts of survivors Peter Thompson and August De Voto, and an Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant who was an eye-witness to the condition of the battlefield immediately afterwards.

Thompson provides the strongest testimony. He said he and fellow Seventh Cavalry straggler James Watson were fleeing some Sioux on the banks of the Little Bighorn when they encountered a white man and an Indian whom they at first took for friends — until the pair dismounted, “threw their guns across their saddles” and fired at them, sending Thompson and Watson fleeing.

After the battle, August De Voto said, “we went over the ground where the Indian camp had been. There were two tepees left standing full of dead Indians. As we rode past I looked in. They were piled up like cord wood. One of them looked to me very much like a white man. I could not see his face, but his legs looked white. I had no chance to go in and make a close investigation.”

Other Seventh cavalry survivors made similar statements. In a 1904 interview with Walter Mason Camp, John Martin said he saw the corpse of a white man in the village after the battle, and Camp‘s comments indicate Daniel Kanipe also told Camp that he saw a dead white man in the village after the battle.

An Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant added, “One of the Indians that was shot by [Major Marcus] Reno‘s men attracted peculiar attention, and upon going up to him he was found masked, and upon removing the mask the features of a white man were disclosed, with a long, gray, patriarchial beard.”

So who knows? Maybe there was one or more white men fighting on the Sioux and Cheyenne side, but the next question is, “did it matter?” and the answer is, “no, it didn’t matter.” As Short Bull observed of Crazy Horse as he turned from Reno to flank Custer‘s decapitated command, the Sioux and Cheyenne had their “business well in hand” that day…

* * *

Q: Did any of Custer’s men manage to get across the Little Bighorn River into the Cheyenne camp when Custer attacked the village at Medicine Tail Coulee?

A: Yes, according to the eye-witness record, at least one Seventh Cavalry trooper made it across the river before (or in the moments immediately after) Custer was shot mid-river by White Cow Bull, and the American attack collapsed. [Note: see Who Killed Custer – The Eye-witness Answer for more info.]

On August 1, 1876 — six weeks after the battle — a group of Seven Anonymous Sioux and Cheyenne warriors told Capt. John Polland: “he [Custer] crossed the river, but only succeeded in reaching the edge of the Indian camp.”

Crow scout Curley, who was an eye-witness to Custer‘s attack at Medicine Tail Coulee, said in 1916, “The bugler got killed in the camp. Some of them got killed in the river. They (the Sioux) would not let the soldiers cross the river.”

Arapaho warrior Sage also spoke of two wounded Americans found at the edge of the river who were killed by the Indians — Custer’s head scout, Mitch Bouyer (or Boyer), and “a soldier with a bugle and a carbine.”

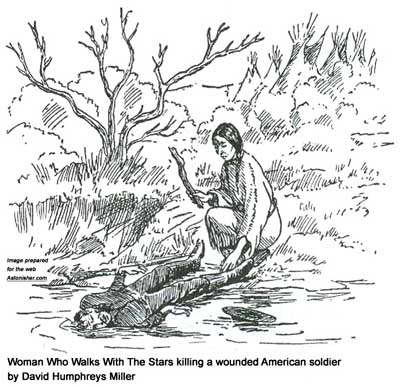

Brule Sioux warriors Hollow Horn Eagle and Brave Bird agreed, adding that the bugler was wounded on the Cheyenne side of the river, and killed there after the battle by Woman Who Walks With The Stars, the wife of Brule Sioux chief Crow Dog. “For some reason he was trying to get back across the river,” Hollow Horn Eagle and Brave Bird observed dryly…

* * *

Q: Were any of Custer’s men drinking alcohol during the battle?

A: This assertion was publically aired in the aftermath of the great American defeat. Custer loyalists claimed that Marcus Reno was drunk going into battle, and this was one of the charges against Reno in the Court of Inquiry that was convened on November 25, 1878. Reno was exonerated by the U.S. Army of this — and all other charges against him — the following spring.

However, there is one mention of drinking by Reno in the eye-witness record left by American survivors of the battle. William O. Taylor remembered seeing a flask pass between the officers moments before the fighting began while they were charging toward the huge village:

“The Major and Lieutenant [Benjamin H.] Hodgson were riding side by side a short distance in the rear of my Company. As I looked back Major Reno was just taking a bottle from his lips. He then passed it to Lieutenant Hodgson. It appeared to be a quart flask, and about one half or two thirds full of an amber colored liquid. There was nothing strange about this, and yet the circumstances remained indelibly fixed in my memory. I turned my head to the front as there were other things to claim my attention. What that flask contained, and effect its contents has, is not for me to say, but I have ever since had a very decided belief…”

That belief was, of course, that the flask contained whiskey. Perhaps it did, and perhaps the officers in Reno’s command took a shot as the charged to attack the huge Sioux and Cheyenne village, and an enemy force that out-numbered them by at least 10-to-1. It’s not hard to believe, frankly, nor does it seem like unreasonable or shameful behavior under the circumstances.

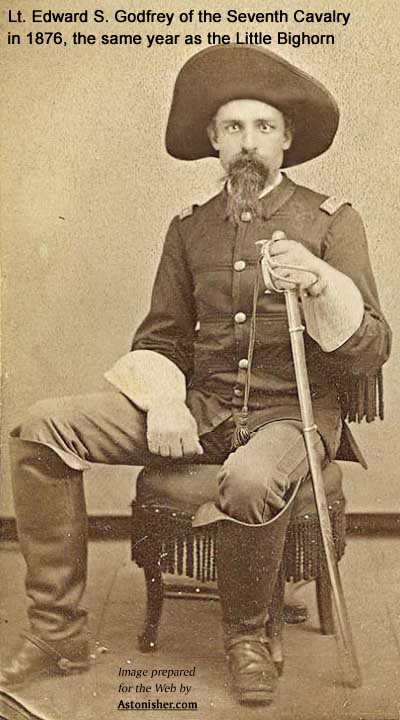

Either way, the eye-witness record clearly indicates that Reno and his men showed tremendous courage at the outset of the battle, and his command of his troops was firm. He executed the first charge, the first skirmish line and the retreat to the second defensive position in the timber along the river crisply, and when his men started whooping in mocking imitation of the Indians, both Edward Godfrey and William O. Taylor recalled Reno immediately ordered them to “stop that noise!”

About whiskey specifically, Godfrey said,

“I have seen articles imputing wholesale drunkenness to both officers and enlisted men, including General Custer who was absolutely abstemious. I do not believe that any officer, except Major Reno, had any liquor in his possession. Major Reno had half a gallon keg that he took with him in the field, but I don’t believe any other officer sampled its contents. I saw all the officers early in the morning and again at our halt at the divide and when officers’ call was sounded to announce the determination to attack, and I saw no sign of intoxication; all had that serious, thoughtful mien, indicating that they sensed the responsibilities before them.”

However, there is considerable testimony in the Sioux and Cheyenne eye-witness record about drunkeness among the Seventh Cavalry soldiers with Custer, all of whom perished. Lazy White Bull, Soldier Wolf, Hollow Horn Bear and Iron Hawk all said Custer’s men acted “drunk,” although some historians have theorized that Custer’s men were actually “demoralized” by the situation Custer had gotten them in.

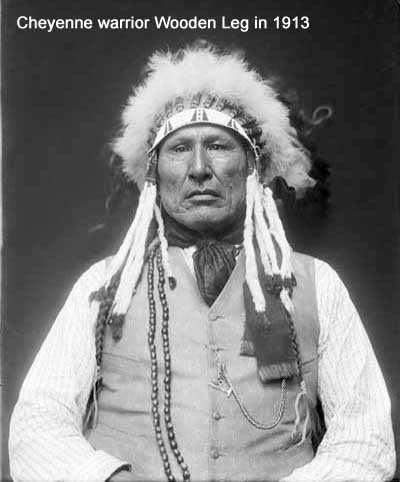

Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg said he found some of the whiskey on one dead Seventh Cavalry soldier. Wooden Leg gave it to his friend Little Hawk, who promptly drank some and got sick:

“[After the battle with Custer was over,] I found a metal bottle, as I was walking among the dead men. It was about half full of some kind of liquid. I opened it and found that the liquid was not water. Soon afterward I got hold of another bottle of the same kind that had in it the same kind of liquid. I showed these to some other Indians. Different ones of them smelled and sniffed. Finally a Sioux said:

“‘Whiskey.’

“Bottles of this kind were found by several other Indians. Some of them drank the contents. Others tried to drink, but had to spit out their mouthfuls. [Cheyenne warrior] Bobtail Horse got sick and vomited soon after he had taken a big swallow of it. It became the talk that this whisky explained why the soldiers became crazy and shot each other and themselves instead of shooting us. One old Indian said, though, that there was not enough whisky gone from any of the bottles to make a white man soldier go crazy. We all agreed then that the foolish actions of the soldiers must have been caused by the prayers of our medicine men.

“I believed this was the true explanation. My belief became changed, though, in later years. I think now it was the whiskey… I passed one bottle of the whisky among friends. Each took a small drink of it until all of it was gone. The other bottle I gave to Little Hawk. He himself drank all of the whisky in it. Pretty soon, though, he became sick and he vomited up everything in his stomach.

* * *

Q: What happened at the “Lone Tepee”?

A: Mention of the so called Lone Tepee is a thread that runs through the eye-witness accounts of many American, Crow, Arikara and Sioux accounts of the battle, and it serves as a sort of “clapper board” to synchronize the chronology of many independent and separate stories.

Sioux warrior Old Eagle said the Lone Tepee contained the body of a dead Sioux warrior named Old She Bear. He said the Lone Tepee stood where Old She Bear’s band of free Sioux were camped at the time of the Battle of the Rosebud:

“Old She Bear was a Sans Arc, a brother of Chief Circling Bear. As a warrior under the aegis of Crazy Horse, fighting genius of the Ogalalas, he had played a prominent part in the triumph over [General] Crook on the Rosebud, and had suffered a critical wound — a soldier’s bullet through both hips. Circling Bear’s cohorts had brought him here to the band’s temporary camp on Ash Creek, where he had lingered on for several days. Then, while the life slowly ebbed from him and most of the band moved on to the Little Big Horn four miles downstream, only his wife and a few kinsmen stayed on to the end.”

Old Eagle went on to describe the prophesy ceremony he and Two Bears performed for Old She Bear in the final hours of the dying warrior’s life:

“Later on in the day Old Eagle and Two Bears had gone out to kill a badger. They brought back the carcass and slit open the belly, after an age-old Sioux custom. Removing the entrails, they allowed the blood to congeal. Then they propped up the wounded warrior so he could use the coagulated blood as a mirror. It was an ancient device for predicting the future. If a warrior saw a youthful image in the jelled blood, he would die young. If he saw the reflection of an aged person, he might count on living a long time. Old She Bear stiffened perceptibly as he saw himself much as he was — a relatively young man. As he drew back in dismay, Two Bears stooped over him. He, too, saw his own youthful image reflected in badger blood.”

After Old She Bear died, Old Eagle said he and Two Bears:

“painted the dead warrior’s face red, and dressed him in his ceremonial buckskins. His widow cut off her heavy braids and gashed her legs with a sharp knife. Her keening could be heard for over a mile up and down the creek. Once her husband’s body was ready and placed on a cottonwood log scaffold six feet high, she pitched the lodge over him for the last time.”

Using face paint, Old Eagle and Two Bears marked sacred symbols on the outside of the tepee. They would help to draw Wakan Tanka’s attention to Old She Bear’s departing spirit and insure its arriving safely in the Last Hunting Ground. Normally, the process of decorating the lodge for burial would have taken several hours. But the variety of clay pigment in the area was limited, so they had to make out with few colors. The painting and ornamentation were completed soon after midday, just as Old She Bear’s widow and her aging aunt were striking the other lodges and loading their belongings on the pony drags [travois] for the move downstream to the Little Big Horn.

Several days later, Arikara scout Young Hawk recalled finding the Lone Tepee as the Seventh Cavalry charged to attack the free Sioux and Cheyenne at the Battle of the Little Bighorn:

“They went down the dry coulee [Medicine Tail Coulee] and when about half way to the high ridge at the right, Young Hawk saw a group of scouts at the lower end of the ridge peering over toward the lone tepee. The scouts he was with slowed up as the others came toward them. Then behind them they heard a call from [Fred] Gerard. He said to them: “The Chief says for you to run.” At this Strikes Two gave the war-whoop and called back: “What are we doing?” and rode on. At this we all whooped and Strikes Two reached the lone tepee first and struck it with his whip. Then Young Hawk came. He got off on the north side of the tepee, took a knife from his belt, pierced the tent through and ran the knife down to the ground. Inside of the lone tepee he saw a scaffold, and upon it a dead body wrapped in a buffalo robe.“

Fellow Arikara scout Red Bear further elaborated on the encounter between Custer and the Arikara scouts at the Lone Tepee, which stands out as one of the few moments of humor on the battlefield:

“Custer had ordered the charge and he also gave them orders to take the Dakota horses from their camp. The scouts charged down the dry run [Medicine Tail Coulee], and when Red Bear came to the lone tepee, the other scouts were ahead of him and were riding around the lone tepee, striking it with their whips. He did this also. All the scouts stopped at the lodge perhaps half an hour. One of them called out: “There is plenty of grub here.” One Feather went into the tepee and drank the soup left for the dead Dakota warrior and ate some of the meat. Just then Custer rode up with [Fred] Gerard and the latter called out to them: “You were supposed to go right on in to the Sioux village.” While the scouts were examining the lone tepee, Custer, who was ahead of his troops, overtook them and said by words and signs: “I told you to dash on and stop for nothing. You have disobeyed me. Move to one side and let the soldiers pass you in the charge. If any man of you is not brave, I will take away his weapons and make a woman of him.” One of the scouts cried out: “Tell him if he does the same to all his white soldiers who are not so brave as we are, it will take him a very long time indeed.” The scouts all laughed at this and said by signs that they were hungry for the battle. They rode on ahead at this, but Red Bear noticed that Custer turned off to the right with his men about fifty yards beyond the lone tepee.”

At some point, someone lit the Lone Tepee on fire. Edward Godfrey and Charles Windolf speculated that this was done by Custer’s Indian scouts, but the Indians vehemently denied the accusation. Instead, Crow scout White Man Runs Him remembered:

“About nine miles down the Upper Fork of Ash Creek, we found a lodge with a dead Indian inside… As we passed by, some soldiers set fire to this lodge.”

Frederick Benteen, who commanded one of Custer’s three wings after he divided his command, passed the Lone Tepee shortly after this, judging by his account: “I then marched rapidly and after about 6 or 7 miles came upon a burning tepee in which was the body of an Indian on a scaffold, arrayed gorgeously. None of the command was in sight at this time…”

* * *

Q: Why did the Seventh Cavalry carry a great deal of salt to the Battle of the Little Bighorn?

A: In short, Custer’s orders. As “A Prominent Officer” in Custer’s command wrote in an anonymous column that ran in the New York Herald after both Custer and the Prominent Officer were killed in the battle:

“Custer advised his subordinate officers, however, in regard to rations, that it would be well to carry an extra supply of salt, because, if at the end of fifteen days the command should be pursuing a trail, he did not propose to turn back for lack of rations, but would subsist his men on fresh meat-game, if the country provided it; pack mules if nothing better offered.”

Lt. Edward Godfrey confirmed this. He recalled the Officers’ Call meeting just before the Seventh Cavalry headed for the Little Bighorn, when Custer’s disclosed his general plan of attack to his subordinate officers:

“[T]urning as he was about to enter his tent, he [Custer] added: “You had better carry along an extra supply of salt; we may have to live on horse meat before we get through.” He was taken at his word, and an extra supply of salt was carried.”

After the battle, Little Bighorn survivor William O. Taylor commented dryly:

“It has always seemed rather strange to me that the remains of General Custer were not brought along with the wounded and shipped with them on the steamer Far West, to Fort Lincoln. There was plenty of salt and strong canvas to wrap the body in, and the steamer was but a few miles away. The Indians carried away many of their dead, why could not the white man do as much for one as distinguished as General Custer?”