|

|||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... John Stands In Timber's

THE CUSTER FIGHT

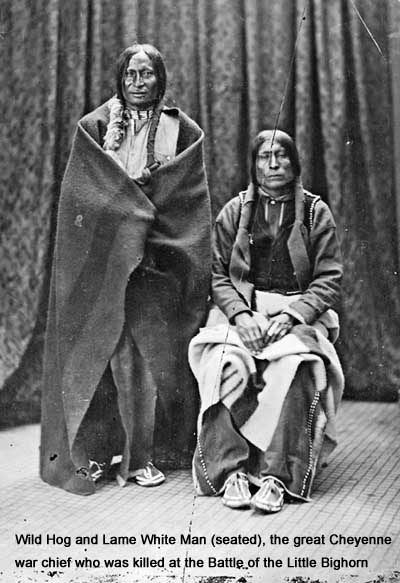

But they were not ignorant on the other side either. A Crow, White Man Runs Him (one of Custer's scouts), told the Cheyennes that they were watching the Indians and each day took word to Custer of what they were doing. So each party knew pretty well where the other was. After the main camp on the Little Horn had been established the Sioux leaders sent word that they wanted all the chiefs to gather to discuss what to do if the soldiers came. They had decided not to start anything, but to find out what the soldiers were going to do, and to talk to them if they came in peacefully. "It may be something else they want us to do now, other than go back to the reservation," they said. "We will talk to them. But if they want to fight we will let them have it, so everybody be prepared." They also decided that the camp should be guarded by the military societies, to keep individual warriors from riding out to meet the soldiers. It was a great thing for anyone to do that-to go out and meet the enemy ahead of the rest-and they did not want this to happen. So it was agreed that both the Sioux and Cheyenne military societies would stand guard. Each society called its men, and toward evening they went on duty. Bunches of them rode to ten or fifteen stations on both sides of the river, where they could keep good watch. About sundown they could be seen, all along the hills there. There was good reason for them to watch well. The people usually obeyed the orders of the military societies. Punishment was too severe if they did not. But that night the young men were determined to slip through. Soon after they had begun patrolling, my step-grandfather's friend Big Foot came to him. "Wolf Tooth," he said, "we could get away and go on through. Maybe some others will too, and meet the enemy over on the Rosebud." They began watching to see what the military societies were doing, and to make plans. They saw a bunch of them start across to the east side of the river and another bunch on the hill between the Reno and Custer battlefields. Many more were on the high hills at the mouth of Medicine Tail Creek. So they decided what to do. After sundown they took their horses way up on the west side of the river and hobbled them, pretending to be putting them there so they could get them easily in the morning. Then they returned to camp. But when it was dark they walked back out there and got the horses, and went back down to the river. When they did they heard horses crossing and were afraid to go ahead. But the noise died away, and they went on into the river slowly, so even the water would splash more quietly. They got safely to the other side and hid in the brush all night there so they would not be discovered. In the meantime, there was some excitement in the camp. Some of the Sioux boys had just announced that they were taking the suicide vow, and others were putting on a dance for them at that end of the camp. This meant they were throwing their lives away -- they would fight till they were killed in the next battle. The Cheyennes had originated the suicide vow. Then the Sioux learned it from them, and they called this dance put on to announce it "Dying Dancing." A few Cheyenne boys had announced their decision to take the vow at the same time, so a lot of Cheyennes were up there in the crowd watching. Spotted Elk and Crooked Nose are two who remembered that night and told me about it. Both of them have been dead for a long time now. They said the people were already gathering, early in the evening. By the time they got to the upper end there a big place had been cleared and they were already dancing. When those boys came in they could not hear themselves talk, there was so much noise, with the crowd packed around and both the men and women singing. They do not remember how many took part and never thought of counting them, but Spotted Elk said later there were not more than twenty. They remembered the Cheyenne boys that were dancing: Little Whirlwind, Cut Belly, Closed Hand, and Noisy Walking. They were all killed the next day. [Note: here is Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg's account of Little Whirlwind's death and Noisy Walking's death.] None of them knew for sure that night that the soldiers were coming next day. They were just suspicious. The next morning the Indians held a parade for the boys who had been in the suicide dance the night before. Different ones told me about it. One was my grandmother Twin Woman, the wife of Lame White Man, the only Cheyenne chief who was killed in the battle. It was customary to put on such a parade after a suicide dance. The boys went in front, with an old man on either side announcing to the public to look at these boys well; they would never come back after the next battle. They paraded down through the Cheyenne camp on the inside and back on the outside, and then returned to their own village. While the parade was still going on, three boys went down to the river to swim -- William Yellow Robe, Charles Head Swift, and Wandering Medicine. They were down there in the water when they heard a lot of noise and thought the parade had just broken up. Some riders in war clothes came along the bank yelling and shooting. Then somebody hollered at them, "The camp is attacked by soldiers!" So they never thought about swimming anymore. They jumped out and ran back to their families' camps. Head Swift's had already run away toward the hills on the west side, but his older brother came back after him. They had to run quite a distance to get his brother's horse. Then they rode double to join the women and children where they were watching the beginning of the fight. Yellow Robe's good horse that he had staked close by had broken loose and gotten away, so he had to catch another one, and got a half-broke colt. It stampeded with him and almost ran over some people. He could not guide it, but it did not buck so he stuck on, following after the rest across the hills. If he had had his own horse he would have been in the fight. Meanwhile, after the parade ended my grandmother said a man named Tall Sioux had put up a sweat lodge, and Lame White Man went over to take part in his sweat bath there. It was just a little way from the tepees. She said they had closed the cover down a couple of times -- they usually did it four times in all, pouring water on the hot stones to make steam-and the second or third time the excitement started in the valley above the village. She did not see which way the soldiers came, but there were some above the village. And some more came from straight across the river. The men in the sweat tepee crawled out and ran to help their families get on their horses and get away. Lame White Man did not have time to get war clothes on. He just wrapped a blanket around his waist and grabbed his moccasins and belt and a gun. He went with Grandmother a little way to the west of some small hills there. Then he turned down below and crossed after the rest of the warriors. Wolf Tooth and Big Foot had come out of the brush long before then. At daylight they could see the Indian military :patrols still on the hills, so they waited for some time. They moved along, keeping under cover, until they ran into more warriors and then some more. Close to fifty men had succeeded in slipping through and crossing the river that way. They got together below the creek that comes in north of the present Highway 212 and were about halfway up a wooded hill there when they heard someone hollering. Wolf Tooth looked back and saw a rider on a ridge a mile below them, calling and signaling them to come back. They turned and galloped back, and when they drew near, the rider began talking in Sioux. Big Foot could understand it. The soldiers had already ridden down toward the village. Then this party raced back up the creek again to where they could follow one of the ridges to the top, and when they got there they saw the last few soldiers going down out of sight toward the river --Custer's men. Reno's men had attacked the other end already, but they did not know it yet. As the soldiers disappeared, Wolf Tooth's band split up. Some followed the soldiers, and the rest went on around a point to cut them off. They caught up there with some that were still going down, and came around them on both sides. The soldiers started shooting. It was the first skirmish of the battle, and it did not last very long. The Indians said they did not try to go in close. After some shooting both bunches of Indians retreated back to the hills, and the soldiers crossed the south end of the ridge where the monument now stands. The soldiers followed the ridge down to the present cemetery site. Then this bunch of forty or fifty Indians came out by the monument and started shooting down at them again. But they were moving on down toward the river, across from the Cheyenne camp. Some of the warriors there had come across, and they began firing at the soldiers from the brush in the river bottom. This made the soldiers turn north, but they went back in the direction they had come from, and stopped when they got to the cemetery site. And they waited there a long time-twenty minutes or more. The Indians have a joke about it. Beaver Heart said that when the scouts warned Custer about the village he laughed and said, "When we get to that village I'm going to find the Sioux girl with the most elk teeth on her dress and take her along with me." So that was what he was doing those twenty minutes, looking. [Note: Medal of Honor winner Peter Thompson said he saw Custer at the river in a bizarre scene with a Crow scout and a Sioux women on a tether.] Hanging Wolf was one of the warriors who crossed the river and shot from the brush when Custer came down to the bottom. He said they hit one horse down there, and it bucked off a soldier, but the rest took him along when they retreated north. [Note: White Cow Bull says that when Custer's men tried to ford the river he shot a man in buckskin on a sorrel horse with white socks -- only Custer fit that description. See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.] More Cheyennes and Sioux kept crossing all the time as the soldiers moved back up toward the top. Hanging Wolf thought they could have gone back between the river and the top of the ridge and made it back to Reno. But they waited too long. It gave many more warriors a chance to get across and up behind the big ridge where the monument stands, to join Wolf Tooth and the others up there. Wolf Tooth and his band of warriors had moved in, meanwhile, along the ridge above the soldiers. Custer went into the center of a big basin below the monument, and the soldiers of the gray horse company got off their horses and moved up afoot. If there had not been so many Indians on the ridge above they might have retreated over that way, either then or later when the fighting got bad, and gone to join Reno. But there were too many up above, and the firing was getting heavy from the other side also. Most of the Cheyennes were down at the Custer end of the fight, but one or two were up at the Reno fight with the Sioux. Beaver Heart saw Reno's men come in close to the village and make a stand there in some trees after they had crossed the river. But they were almost wiped out. They got on their horses and galloped along the edge of the cottonwood trees on the bank and turned across the river, but it was a bad crossing. The bank on the other side was higher and the horses had to jump to get on top. Some fell back when it got wet and slick from the first ones coming out, and many soldiers were killed, trying to get away. Some finally made it up onto the hill-the one that is called Reno Hill today -- where they took their stand. It was about that time that Custer was going in at the lower end, toward the Cheyenne camp. It was hard work to keep track of everthing at the two battles. A number of Indians went back and forth between the two, but none of them saw everything. Most of them went toward the fight with Custer, once Reno was up on the hill. Wolf Tooth said they were all shooting at the Custer men from the ridge, but they were careful all the time, taking cover. Before long some Sioux criers came along behind the line calling in the Sioux language to get ready and watch for the suicide boys. They said they were getting ready down below to charge together from the river, and when they came in all the Indians up above should jump up for hand-to-hand fighting. That way the soldiers would not have a chance to shoot, but be crowded from both sides. The idea was that the soldiers had been firing both ways. When the suicide boys came up they would turn toward them, and give those behind a chance to come in close. The criers called out those instructions twice. Most of the Cheyennes could not understand them, but the Sioux there told them what had been said. So the suicide boys were the last Indians to enter the fight. Wolf Tooth said they were really watching for them, and at last they rode out down below. They galloped up to the level ground near where the museum now is. Some turned and stampeded the gray horses of the soldiers. By then they were mostly loose, the ones that had not been shot. The rest charged right in at the place where the soldiers were making their stand, and the others followed them as soon as they got the horses away. The suicide boys started the hand-to-hand fighting, and all of them were killed or mortally wounded. When the soldiers started shooting at them, the Indians above with Wolf Tooth came in from the other side. Then there was no time for them to take aim or anything. The Indians were right behind and among them. Some started to run along the edge under the top of the ridge, and for a distance they scattered, some going on one side and some the other`. But they were all killed before they got far. At the end it was quite a mess. They could not tell which was this man or that man, they were so mixed up. Horses were running over the soldiers and over each other. The fighting was really close, and they were shooting almost any way without taking aim. Some said it made it less dangerous than fighting at a distance. Then the soldiers would aim carefully and be more likely to hit you. After they emptied their pistols this way there was no time to reload. Neither side did. But most of the Indians had clubs or hatchets, while the soldiers just had guns. They were using these to hit with and knock the enemy down. A Sioux, Stinking Bear, saw one Indian charge a soldier who had his gun by the barrel, and he swung it so hard he knocked the Indian over and fell over himself. Yellow Nose was in there close. He saw two Indian horses run right into each other. The horses both fell down and rolled, and he nearly ran into them himself but managed to turn aside. The dust was so thick he could hardly see. He swung his horse out and turned to charge back in again, close to the end of the fight, and suddenly the dust lifted away. He saw an American flag not far in front of him, where it had been set in the sagebrush. It was the only thing still standing in that place, but over on the other side some soldiers were still fighting. So he galloped past and picked the flag up and rode into the fight, and he used it to count coup on a soldier. Yellow Nose told that story many times. They used to hold special dances. An old man would start them, telling some great things he had done in battle. He told it then, and also at camp gatherings of the Oklahoma Cheyennes when the Dog Soldiers used to sing all night in front of different tepees. Early in the morning they would dance toward the center of the village, and any brave man could come before them on foot or on horseback and stop them, and tell what he had done. I heard him then too. The coups were counted differently that day, though. No one could tell who had really been first to touch a certain enemy, so they just counted second and third. After the suicide boys came in it didn't take long-half an hour perhaps. Many have agreed with what Wolf Tooth said: that if it had not been for the suicide boys it might have ended the way it did at the Reno fight. There the Indians all stayed back and fought. No suicide boys jumped in to begin the handto-hand fight. The Custer fight was different because those boys went in that way, and it was their rule to be killed. Another thing many of the Cheyennes said was that if Custer had kept going-if he had not waited there on the ridge so long -- he could have made it back to Reno. But probably he thought he could stand off the Indians and win. Everyone always wants to know who killed Custer. I have interpreted twice for people asking about this, and whether anyone ever saw a certain Indian take a shot and kill him. But they always denied it. Too many people were shooting. Nobody could tell whose bullet killed a certain man. There were rumors some knew but would not say anything for fear of trouble. But it was more like Spotted Blackbird said: "If we could have seen where each bullet landed we might have known. But hundreds of bullets were flying that day." There all kinds of stories though. I even heard that some Sioux had a victory dance that night, and some Cheyennes that went over there said they saw Custer's head stuck on a pole near the fire. They were having a big time over that head. But the other story is, the body was not even scalped. Anyway they are all gone now, and if anyone did know it is too late to find out. After they had killed every soldier, my grandmother's brother Tall Bull came across and said, "Get a travois fixed. One of the dead is my brother-in-law, and we will have to go over and get his body." It was my grandfather, Lame White Man. So they went across to where he was lying. He did not have his war clothes on. As I said, he had not had time. And some Sioux had made a mistake on him. They thought he was an Indian scout with Custer -- they often fought undressed that way. And his scalp was gone from the top of his head. Nearby was the body of another Cheyenne, Noisy Walking. They were the only ones to have the places marked where they were found. Lame White Man was the oldest Cheyenne killed, and the only Cheyenne chief. I heard that the Sioux lost sixty-six and the Cheyennes just seven, but there might have been more. The Indian dead were all moved from the battlefield right away. Four Cheyennes had been killed outright and the others badly wounded. Two died that night and one the next day. These were the dead: my grandfather; Noisy Walking, the son of White Bull or Ice; Roman Nose, the son of Long Roach; Whirlwind, the son of Black Crane; Limber Bones; Cut Belly; and Closed Hand. Closed Hand, Cut Belly, Noisy Walking, and Whirlwind had been suicide boys. They were all young men. The Cheyenne dead were buried on the other side of the river, near where the railroad tracks now run. Some said the ones who died later, after the battle, were taken up to a place near the forks of Reno Creek several miles east of the river. We looked around there once and found one old-fashioned grave, with hides and pillows made of deer hair, and room enough under the sand rock for two or three bodies. It might have been the place. Someone had moved the rock, and a lot of stuff was lying outside there, and some human bones.

The Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg in his book told about my grandfather being killed. He said he recognized the body by the shirt and warbonnet, but he was mistaken. Larne White Man did not have anything on but a blanket and moccasins. He had not even had time to braid his hair. That was why the Sioux thought he was a scout for Custer, and scalped him. Wooden Leg said some other things he took back later. One was that the soldiers were drunk, and many killed themselves. I went with two army men to see him one time. They wanted to find out about it. I interpreted. They took him some tobacco and cash and other things, and we asked him if it were true that the Indians said the soldiers did that. He laughed and said there were just too many Indians. The soldiers did their best. He said if they had been drunk they would not have killed as many as they did. But it was in the book. Many Indians were up on the battlefield after it was over, getting the dead or taking things from the soldiers. I never heard who damaged the bodies up there. I asked many of them, and most said they did not go. A few said they had seen others doing it. They did scalp some of the soldiers, but I don't think they took the scalps into camp. The ones who had relatives killed at Sand Creek came out and chopped the heads and arms off, and things like that. They took what they wanted, coats and caps -- they never used pants or shoes. Some claimed they never touched them while others said they took things. But those who had relatives at Sand Creek might have done plenty. I asked Grandmother if she went. Women were up there as well as men. But she said the fight was still going on up above with Reno, and many women were afraid to go near the field. They thought the soldiers might break away and come in their direction. She was busy anyway, with my grandfather's body. But I think many never admitted what they did. At least nobody would tell the details of what was done to those soldiers' bodies. White Wolf (also called Shot in the Head), who was in this fight, said that afterwards a lot of young men picked up silver and paper money. Two different ones said they put it in saddle bags they had taken, and carried them up to Reno Creek and cached them in pockets in the sand rocks. They rode up close to the rocks and stood on their horses and pushed the sacks in there. They might still be there some place, but the story has been told many times, and they might have been found. We went over to look ourselves, once, but we did not have time to search every place where they might have been. There was a good deal of money picked up after the battle, though. No one knows what happened to it all. Wandering Medicine, who was a boy then, told how he and other boys searched some of the soldiers' pockets. That square green paper money was in them, and some lying around on the ground. So they took some. Later when they were making mud horses they used it for saddle blankets. And silver money was found too. The Cheyennes made buckles out of it. They pounded it with heavy iron to flatten it out and made holes on each side, or they would string pieces together and use them for hair ornaments or necklaces, or put them on bridles as Limpy's father did. They cut up some of the uniforms they took from the soldiers and made leggings of them. Some they just wore for coats and jackets. And they took other things. Wolf Tooth had the top of a boot cut off and sewed to make a bag. He had pliers and reloaders for a gun in that bag, and they were put away in his grave when he was buried out in the hills. I rode close to his grave a few years ago and went over and looked for it. Someone must have taken it, though I found some shells nearby. And I saw a saddle owned by one old man who had been at the battle. It was old-time Indian style, but the stirrups had come from a soldier's saddle. And some of them got canteens and guns and shells. Long after the reservation was established in 1884, some still had those guns they had taken. In one picture of White Bull, he is holding a gun he grabbed away from a soldier. He told the trader A.C. Stohr about it. When his house burned down the gun was burned too, except for the barrel, but Stohr bought it from him anyway. And Wooden Leg is holding a captured gun in the picture in his book. They should mark more places on the battlefield, from the Indian side. They told me some of the stories over and over for many years, and remembered where things happened. I have marked many of the places myself with stones. but it's getting harder for me to find them now. I have tried to show other people the places so they would not be forgotten, and tell them what happened there. One is at the Reno field where a young Sioux boy charged the soldier line and was killed, following an older warrior. He was the one who lost his brother in the Rosebud fight and did not want to live any longer. Another is where Low Dog, a Sioux, and Little Sun killed a soldier. They had been back and forth between the two fights. They were just leaving the Reno fight to go down toward Custer when one soldier on a fast horse came from Custer's direction toward Reno Hill. They tried to head him off, but he got through them, so they turned to chase him. When they crossed Medicine Tail Coulee, Low Dog jumped off his horse. He was a good shot. He sat down to take good aim, and fired and knocked the rider off as he was going over a little knoll. Then two or three Sioux came by and took after the horse, but Little Sun did not see whether they caught it. The big camp broke up the next day after the battle. Some people even left that evening, to move up near Lodge Grass. Some of the warriors stayed behind to go on fighting with Reno, but they did not stay more than a day. They knew that other soldiers were in the country, and they were out of meat and firewood. The camp was too big to stay together for long. They split into many groups, some following the river and others going up Reno Creek, and to other places. My grandmother was with the Cheyennes who went toward Lodge Grass. She told a funny story of what happened there. They were camped on a big flat, some Cheyennes and some Sioux. And the Sioux dressed up soldier-style in the things they had captured, and held a parade. They were just having fun, showing off. They had a bugle. You could hear them blowing it before they reached the camp. And they had captured some of the gray horses, maybe ten or fifteen, after the suicide boys went in and stampeded them. They rode all these grays in a line carrying a flag. One was my grandmother's. White Elk had borrowed one of her horses for the battle, so he gave her one of the two grays he captured. When they had this parade, the Sioux came over and borrowed him for awhile. Those fellows made quite a sight. Spotted Hawk told about it too. They came down along the camp in line, wearing the blue uniforms and soldiers' hats on their heads with the flag and the bugle and the gray horses. But none of them had pants on. They had no use for pants. The parade was in the morning. They had a victory dance that night. They had a fine time. The next day they moved on again, to hunt and gather wild fruit and get ready for winter. Many different men told me about that battle. If a person kept listening he would hear a great deal. The ones who told me most about the battle were Wolf Tooth, who raised me, and Black Horse, and Frank Lightning. And Old Bull. He was a young boy at the time, but his father was in the battle, so he knew the story well. And my grandmother, Twin Woman. She married the Sioux Little Chief later on, and I lived with them awhile. And Hanging Wolf. He was one of the warriors who had crossed the river and shot from the brush when Custer came down to the bottom. I liked Hanging Wolf. When I knew him he was an old man and an honest man, and he told me a lot of stories. Each man saw what he saw, and had his own experiences. There were so many stories that if you could collect them all you would have books full. One interesting thing was told by Plenty Crows. He did not know it until later, but his brothers, both Arikaras, were in the battle on the other side, as scouts for Custer. One was named Bobtailed Bull, and the other Little Soldier or Fighting Bear. Plenty Crows gave two of his sons those names. They are both dead now, but there are descendants who still use them. Plenty Crows learned about his brothers years later. One of them was in on the only horse story that came from the Indian side of the battle. Everyone knows of Comanche, the cavalry horse that was found alive on the battlefield when the soldiers discovered it. But the Indians had a famous horse too, though it was on the soldiers' side. He was ridden by this Arikara scout. He was a big pinto, trained ever since he had been a colt. His mother was a travois mare, and the kids played with the colt so much he was gentle from the time he was small. He would even follow them into a tepee. They trained this horse never to leave when he was turned loose. When this warrior went scouting he never tied him, but left him loose, and he would graze around where the warrior slept. In camp he could make a special noise to call him, and the big pinto would come running, and he would slip the rope over his jaw and jump on. Bobtailed Bull rode this horse into the Custer fight and he was killed there. [Note: here is Sioux warrior Eagle Elk's description of what could be the death of Bob-tailed Bull. Here is Red Bear's account of seeing Bob-tailed Bull's horse with a bloody saddle a few moments later.] The horse was hit twice but not badly, once on the mane and once somewhere else. After the battle he got away and went all the way back to the Arikara reservation. The Indians recognized him, and they always called him Famous War Horse after that time. He is still famous. They made up a song about him way back there, and it was used during the two world wars in a kind of victory dance. They sang it at celebrations when the soldier boys came home. When I heard this I wanted to find out more, and one of the Arikaras gave me a written statement that said: "During my lifetime on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, I can say that a certain Indian war song was composed for a returned wounded pinto horse, whose master was Scout Sergeant Bobtailed Bull, killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn." By the time the other soldiers got to the battlefield the Indians were gone. A Cheyenne named Lost Leg rode back a few days later looking for horses. A lot of them had strayed away and they thought they might be able to get some of them. They said they could smell the battlefield a long way off. They had planned to go in and look at it, but they could not even come close, it was so strong. So they gave up and returned another way to Reno Creek and met some of the Cheyennes moving up that way. There was no more real fighting that summer. Cheyenne Memories by John Stands In Timber and Margot Liberty, Yale University Press New Haven, CN 1967 p 191 - 211

Although John Stands In Timber was not born until a few years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he was the grandson of the great Southern Cheyenne war chief Lame White Man, the step-grandson of the noted Northern Cheyenne warrior Wolf Tooth, and the great-nephew of another noted Cheyenne warrior who fought at the Little Bighorn, Tall Bull. Like Sioux chronicler Dr. Charles Eastman or Ohiyesa, John Stands In Timber had intimate access to numerous Indians who were there, and learned their accounts -- which are set down nowhere else -- first hand. |

|||||||

THE ATTACK of

THE ATTACK of  They put up a sign for my grandfather years later, at the place where he fell. It says, "Lame White Man, a Cheyenne leader, fell here." But he was not really a leader. The Cheyenne chiefs were supposed to stay back. But one might go in and fight with the rest of the warriors, and the younger chiefs often did.

They put up a sign for my grandfather years later, at the place where he fell. It says, "Lame White Man, a Cheyenne leader, fell here." But he was not really a leader. The Cheyenne chiefs were supposed to stay back. But one might go in and fight with the rest of the warriors, and the younger chiefs often did.