|

||||||||||

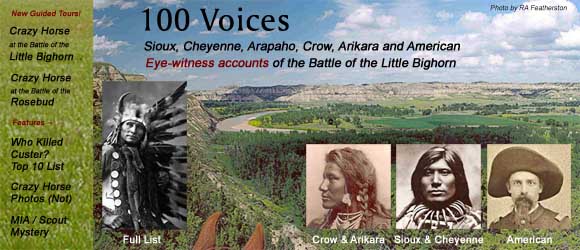

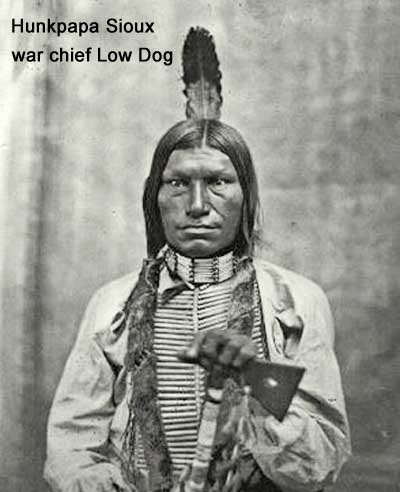

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Low Dog's Story of the Battle

"Then I turned around and went to help fight the other white warriors, who had retreated to a high hill on the east side of the river. (This was Reno's command.) I don't know whether any white men of Custer's force were taken prisoners. When I got back to our camp they were all dead. Everything was in confusion all the time of the fight. I did not see Gen. Custer. I do not know who killed him. We did not know till the fight was over that he was the white chief. We had no idea that the white warriors were coming until the runner came in and told us. I do not say that Reno was a coward. He fought well, but our men were fighting to save their women and children, and drive them back. If Reno and his warriors had fought as Custer and his warriors fought, the battle might have been against us. No white man or Indian ever fought as bravely as Custer and his men. The next day we fought Reno and his forces again, and killed many of them. Then the chiefs said these men had been punished enough, and that we ought to be merciful, and let them go. Then we heard that another force was coming up the river to fight us (General Terry's command,) and we started to fight them, but the chiefs and wise men counseled that we had fought enough and that we should not fight unless attacked, and we went back and took our women and children and went away." This ended Low Dog's narration, given in the hearing of half a dozen officers, some of the Seventeenth Infantry and some of the Seventh Cavalry-Custer's regiment. It was in the evening; the sun had set and the twilight was deepening. Officers were there who were at the Bighorn with Benteen, senior captain of the Seventh, who usually exercised command as a field officer, and who, with his battalion, joined Reno on the first day of the fight, after his retreat, and was in the second day's fight. It was a strange and intensely interesting scene. When Low Dog began his narrative only Capt. Howe, the interpreter, and myself were present, but as he progressed the officers gathered round, listening to every word, and all were impressed that the Indian chief was giving a true account, according to his knowledge. Some one asked how many Indians were killed in the fight, Low Dog answered, "Thirty-eight, who died then, and a great many -- I can't tell the number-who were wounded and died afterwards. I never saw a fight in which so many in proportion to the killed were wounded, and so many horses were wounded." Another asked who were the dead Indians that were found in two tepees-five in one and six in the other-all richly dressed, and with their ponies, slain about the tepees. He said eight were chiefs killed in the battle. One was his own brother, born of the same mother and the same father, and he did not know who the other two were. The question was asked, "What part did Sitting Bull take in the fight?" Low Dog is not friendly to Sitting Bull. He answered with a sneer: "If some one would lend him a heart he would fight." Then Low Dog said he would like to go home, and with the interpreter he went back to the Indian camp. He is a tall, straight Indian, thirty-four years old, not a bad face, regular features and small hands and feet. He said that when he had his weapons and was on the war-path he considered no man his superior; but when he surrendered he laid that feeling all aside, and now if any man should try to chastise him in his humble condition and helplessness all he could do would be to tell him that he was no man and a coward; which, while he was on the warpath he would allow no man to say and live. He said that when he was fourteen years old, he had his first experience on the war-path: "I went against the will of my parents and those having authority over me. It was on a stream above the mouth of the Yellowstone. We went to war against a band of Assiniboins that were hunting buffalo, and I killed one of their men. After we killed all of that band another band came out against us, and I killed one of them. When we came back to our tribe I was made a chief, as no Sioux had ever been known to kill two enemies in one fight at my age, and I was invited into the councils of the chiefs and wise men. At that time we had no thought that we would ever fight the whites. Then I heard some people talking that the chief of the white men wanted the Indians to live where he ordered and do as he said, and he would feed and clothe them. I was called into council with the chiefs and wise men, and we had a talk about that. My judgment was why should I allow any man to support me against my will anywhere, so long as I have hands and as long as I am an able man, not a boy. Little I thought then that I would have to fight the white man, or do as he should tell me. When it began to be plain that we would have to yield or fight, we had a great many councils. I said, why should I be kept as an humble man, when I am a brave warrior and on my own lands? The game is mine, and the hills, and the valleys, and the white man has no right to say where I shall go or what I shall do. If any white man tries to destroy my property, or take my lands, I will take my gun, get on my horse, and go punish him. I never thought that I would have to change that view. But at last I saw that if I wished to do good to my nation, I would have to do it by wise thinking and not so much fighting. Now, I want to learn the white man's way, for I see that he is stronger than we are, and that his government is better than ours." The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania, written and compiled by Colonel W.A. Graham, The Stackpole Co., Harrisburg, PA 1953, p 74 - 76

|

||||||||||

"WE WERE in camp near Little Bighorn river. We had lost some horses, and an Indian went back on the trail to look for them. We did not know that the white warriors were coming after us. Some scouts or men in advance of the warriors saw the Indian looking for the horses and ran after him and tried to kill him to keep him from bringing us word, but he ran faster than they and came into camp and told us that the white warriors were coming. I was asleep in my lodge at the time. `The sun was about noon (pointing with his finger.) I heard the alarm, but I did not believe it. I thought it was a false alarm. I did not think it possible that any white men would attack us, so strong as we were. We had in camp the Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and seven different tribes of the Teton Sioux -- a countless number. Although I did not believe it was a true alarm, I lost no time getting ready. When I got my gun and came out of my lodge the attack had begun at the end of the camp where

"WE WERE in camp near Little Bighorn river. We had lost some horses, and an Indian went back on the trail to look for them. We did not know that the white warriors were coming after us. Some scouts or men in advance of the warriors saw the Indian looking for the horses and ran after him and tried to kill him to keep him from bringing us word, but he ran faster than they and came into camp and told us that the white warriors were coming. I was asleep in my lodge at the time. `The sun was about noon (pointing with his finger.) I heard the alarm, but I did not believe it. I thought it was a false alarm. I did not think it possible that any white men would attack us, so strong as we were. We had in camp the Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and seven different tribes of the Teton Sioux -- a countless number. Although I did not believe it was a true alarm, I lost no time getting ready. When I got my gun and came out of my lodge the attack had begun at the end of the camp where