|

||||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... George A. Custer's Own Account of

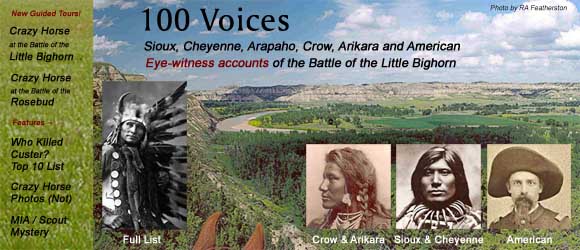

ALTHOUGH IT tells us nothing about the Battle of the Little Bighorn per se, the following dispatch paints a fascinating picture of Custer's command on the eve of the battle: from the blithe humor in the sergeant's drowning at the outset to the sudden dark foreboding around the fire pit at the end. New York Herald correspondent Mark Kellogg's last story, written the day before, provides an additional picture of the American forces as they rode to their annihilation, while One Bull and Standing Bear's eye-witness accounts of the great Sun Dance on the Rosebud in the middle of June provide a perspective on the free Sioux and Cheyenne leading up to the battle, as do the eye-witness accounts of Lazy White Bull, Wooden Leg, and others of Crazy Horse's great victory at the Battle of the Rosebud just eight days before the Battle of the Little Bighorn. According to the New York Herald -- which published it on July 23, 1876 -- the following dispatch was written on June 22, 1876 by a "Prominent Officer Killed in Custer's Last Charge." Some believe the author was George A. Custer himself, and Custer did in fact write a dispatch for Galaxy Magazine immediately prior to June 19, when his command departed the Tongue River for its rendezvous with destiny on the Little Bighorn. Whether Custer personally penned this piece is uncertain. It could have been written by the man the Sioux called Long Hair, or his brother, Capt. Thomas Custer, sarcastically called Little Hair by the Sioux, or one of their associates, but the author was clearly a member of Custer's entourage. * * * IN RETROSPECT, this piece is revealing for the way it attacked Custer's number two in command, Major Marcus Reno, because -- get this -- he showed caution around the combined armies of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse during the summer of 1876! Custer and/or his mouthpiece even suggested that Reno should be court-marshalled for being prudent with the lives of his men scouting the Tongue River while the Seventh Cavalry was enroute to the Little Bighorn. "The details of this affair will not bear investigation," sniffed the self-serving and soon-to-be-dead "Prominent Officer Killed in Custer's Last Charge." Because this dispatch was not published until July 23, 1876, Reno didn't learn about it until after the battle. So when Custer ordered Reno and his 112 men to charge the huge Sioux village on June 25, Reno had no idea Custer had already publically hung him out to dry in the pages of the New York Herald, designating him the scapegoat if the 1876 Sioux campaign failed. Interestingly, Custer's actions on the battlefield that day seem to follow the same pattern verbalized in the following dispatch by a "Prominent Officer Killed in Custer's Last Charge." After ordering Reno to attack, White Man Runs Him recalled, "Custer moved slowly, taking lots of time and stopping occasionally. He did not leave that place [bluffs that afforded a view of the valley below] until Reno had started fighting." Standing Bear, George Glenn and Mrs. Spotted Horn Bull all reported the same thing -- a significant gap in time between Reno's charge and Custer's. White Man Runs Him elaborated in a battlefield interview with Gen. H.L. Scott in 1919, "I have been with other officers of the Army and they attacked differently than Custer did. It did not look right. It was just as if he [Custer] said, 'Reno, you go ahead and let them whip you and then I will go ahead and they will whip me.'" What White Man Runs Him's eye-witness account indicates is that Custer was manuevering on the battlefield -- as he had in the public relations arena with the article for the New York Herald below -- to simultaneously make Reno out to be a failure and set himself up to be the hero who saved the day when the hour was dark. * * * LOOKING AT the plain facts of the matter, one can easily conclude from the eye-witness record of the battle that Custer ruthlessly sacrificed the lives of American soldiers at the Battle of the Little Bighorn -- the Seventh Cavalry troopers killed in Reno's attack -- to set up a scenario where he could appear the heroic savior, and thus enhance his own personal glory.

What Custer actually got, though, was irony wrapped inside irony. It is ironic that Custer was killed by White Cow Bull when he tried to make his heroic, late attack on the huge Indian village, and doubly ironic that Custer's ruthless public relations ploy would largely succeed in America for the next century, despite the fact that he got himself and all his men killed. See Who Killed Custer - The Eye-Witness Answer for more info on Custer, as well as the recollections of Custer loyalist John Burkman and Seventh Cavalry surgeon Dr. Henry Porter. -- Bruce Brown Letter from a Prominent Officer Reno's Contempt of Orders Something for Sherman and Sheridan To Investigate Bighorn Expedition, on Yellowstone River June 22, 1876

Major Reno, whose departure with six companies of the Seventh Cavalry to scout up the Powder River was mentioned in my last letter, moved under written orders, which in substance directed him to scout up the Powder River as far as the mouth of the Little Powder, then across to the headwaters of Mizpah Creek, down that creek to near its mouth, then across to Pumpkin Creek, down that stream to its junction with Tongue River, then down Tongue River to its mouth on the Yellowstone, where he was informed the main part of the expedition would be by the time of his arrival at that point. In the opinion of the most experienced officers it was not believed that any considerable, if any, force of Indians would be found on the Powder River; still there were a few, including Major Reno, who were convinced that the main body of Sitting Bull's warriors would be encountered on Powder River. The general impression, however, is and has been, that on the headwaters of the Rosebud and Little Bighorn rivers the "hostiles" would be found. It was under this impression that General Terry, in framing the orders which were to govern Major Reno's movements, explicitly and positively directed that officer to confine himself to his orders and instructions, and particularly not to move in the direction of Rosebud River, as it was feared that such a movement, if prematurely made, might "flush the covey," it being the intention to employ the entire cavalry force of the expedition, when the time arrived, to operate in the valleys of the Rosebud and Bighorn Rivers. Custer and most of his officers looked with little favor on the movement up the Powder River, as, among other objections, it required the entire remaining portion of the expedition to lie in idleness within two marches of the locality where it was generally believed the hostile villages would be discovered on the Rosebud, the danger being that the Indians, ever on the alert, would discover the presence of the troops as yet undiscovered-and take advantage of the opportunity to make their escape. Reno, after an absence of ten days, returned, when it was found, to the disgust and disappointment of every member of the expedition, from the commanding general down to the lowest private, that Reno, instead of simply failing to accomplish any good results, had so misconducted his force as to embarrass, if not seriously and permanently mar, all hopes of future success of the expedition. [Note: it is not true that Reno returned from the Powder River expedition "to the disgust and disappointment of every member of the expedition, from the commanding general to the lowest private." Neither Sgt. Dan Kanipe or Private John McGuire's accounts of the Powder River foray indicate any "disgust" at all.] He had not only deliberately, and without a shadow of an excuse failed to obey his written instructions issued by General Terry's personal directions, but he had acted in positive disobedience to the strict injunctions of the department commander. [Note: in his eagerness to wrap himself in the mantle of his commanding officer, Custer (or his mouthpiece) neglects to mention that Custer was himself arrested by Terry twice before the expedition got to the Powder River for trying to advance too far ahead of the main column, according to John McGuire.] Instead of conforming his line of march to the valleys and water courses laid down in his written orders he moved his command to the mouth of the Little Powder River, then across to Tongue River, and instead of following the latter stream down to its mouth, there to unite with the main command, he, for some unaccountable and thus far unexplained reason, switched off from his prescribed course and marched across the country to the Rosebud, the stream he had been particularly cautioned not to approach. He struck the Rosebud about twenty-five miles above its mouth, and there -- as Custer had predicted from the first -- signs indicating the recent presence of a large force of Indians were discovered, an abandoned camp ground of the Indians was found, on which 380 lodges had been pitched. The trail led up the valley of the Rosebud. Reno took up the trail and followed it about twenty miles, but faint heart never won fair lady, neither did it ever pursue and overtake an Indian village. Had Reno, after first violating his orders, pursued and overtaken the Indians, his original disobedience of orders would have been overlooked, but his determination forsook him at this point, and instead of continuing the pursuit and at least bringing the Indians to bay, he gave the order to countermarch and faced his command to the rear, from which point he made his way back to the mouth of Tongue River and reported the details of his gross and inexcusable blunder to General Terry, his commanding officer, who informed Reno in unmistakable language that the latter's conduct amounted to positive disobedience of orders, the sad consequences of which could not yet be fully determined. The details of this affair will not bear investigation. A court-martial is strongly hinted at, and if one is not ordered it will not be because it is not richly deserved. The guides who were with Reno report that the trail where the latter was abandoned indicates that the Indian village of 380 lodges was moving in such deliberate manner and left so recently that Reno's command could have overtaken it in a march of one day and a half. Few officers have ever had such a fine opportunity to make a successful and telling strike and few ever failed so completely to improve their opportunities.

Yesterday, Terry, Gibbon and Custer got together, and, with unanimity of opinion, decided that Custer should start with his command up the Rosebud valley to the point where Reno abandoned the trail, take up the latter and follow the Indians as long and as far as horse flesh and human endurance could carry his command. Custer takes no wagons or tents with his command, but proposes to live and travel like Indians; in this manner the command will be able to go wherever the Indians can. Gibbon's command has started for the mouth of the Bighorn. Terry in the Far West starts for the same point today, when with Gibbons force, and the Far West loaded with thirty days' supplies, he will push up the Bighorn as far as the navigation of that stream will permit, probably as far as old Fort C. F. Smith, at which point Custer will reform [rejoin?] the expedition after completing his present scout. Custer's command takes with it, on pack animals, rations for fifteen days. Custer advised his subordinate officers, however, in regard to rations, that it would be well to carry an extra supply of salt, because, if at the end of fifteen days the command should be pursuing a trail, he did not propose to turn back for lack of rations, but would subsist his men on fresh meat-game, if the country provided it; pack mules if nothing better offered. The Herald correspondent will accompany Custer's column and in the event of a "fight or a foot race," will be on the ground to make due record thereof for the benefit of the Herald readers. Upon the march from Powder to Tongue River, Custer, who was riding at the head of the column as it marched through a deserted Indian village of last winter, came upon the skull and bones of a white man. Near these was found the uniform of a cavalry soldier, as shown by the letter "C" on the button of the overcoat and the yellow cord binding on the dress coat. Near by were the dead embers of a large fire; showing, with attendant circumstances, that the cavalryman had undoubtedly been a prisoner in the hands of the savages, and had been put to the torture usually inflicted by Indians upon all white men falling into their hands as captives. Who the unfortunate man was and the sad details of his tragic death will never be known. The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania, written and compiled by Colonel W.A. Graham, The Stackpole Co., Harrisburg, PA 1953, p 62 - 65

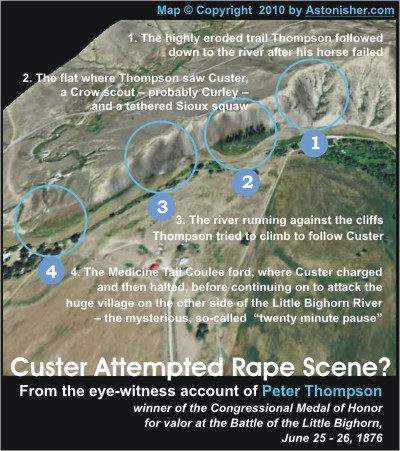

It is possible that George A. Custer committed suicide at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. In fact, based on the eye-witness record of the battle, this is the second most likely kill scenario for Custer, after Sioux White Cow Bull's kill story. See Who Killed Custer - The Eye-Witness Answer for more info. Here is White Cow Bull's further account of how, after the battle was over, he started to mutilate Custer's corpse, but was driven off by the Cheyenne woman called Monaseetah or Meotzi, who had probably been the lover of both Custer and his brother, Capt. Thomas Custer, when she served as a captive interpreter and concubine for the Seventh Cavalry officers after the Washita Massacre. Indian accounts -- including this one by Southern Cheyenne warrior Brave Bear -- say Monaseetah bore one of them a child named Yellow Bird, who was with her in the huge Indian encampment on the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. See Who Killed Custer - Part 11 "War Crime Time" for Medal of Honor winner Peter Thompson's story of catching Custer and one his Crow scouts in the middle of some kinky business with a roped Sioux squaw just before the beginning of the Custer fight. This was actually the last time Custer was seen alive... Another Washita angle at the Little Bighorn: Custer's best battlefield commander on June 25, 1876 was Capt. Frederick Benteen, who had publically called Custer out for abandoning his men eight years before at Washita. Here is the text of the 1868 letter by Benteen that infuriated Custer.

|

||||||||||||

MY LAST LETTER was sent from the mouth of Powder River and described our march from the Little Missouri. I fear it may not have reached its destination, or if it did it was in such a condition as to be illegible owing to a sad accident which befell our mail party. The latter consisted of a sergeant of the Sixth Infantry, Hazen's regiment, and two men of the same command.

MY LAST LETTER was sent from the mouth of Powder River and described our march from the Little Missouri. I fear it may not have reached its destination, or if it did it was in such a condition as to be illegible owing to a sad accident which befell our mail party. The latter consisted of a sergeant of the Sixth Infantry, Hazen's regiment, and two men of the same command.