|

||||||||||||

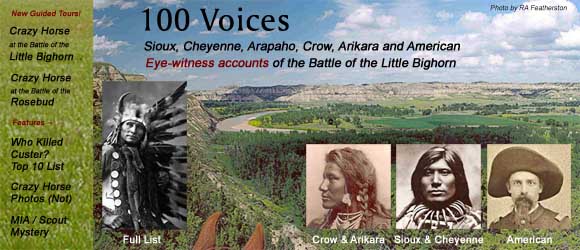

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Iron Hawk's Story of the Battle, #1

IRON HAWK'S ACCOUNT

THE INDIAN tribes who fought Custer were Oglalas, Cheyennes, Rosebud or Brule, Minneconjous, Uncpapas, Santee, a few Arapahoes, and Sans Arcs or No Bows (Itazi Pco, pronounced Etahz Pcho.) The Indians were camped on the Little Big Horn two nights before the Custer battle which began on the third day in the morning.2 The battle began early, about 8 or 9 o'clock, judging from the position of the sun as shown by Iron Hawk. Two young men were going back on the Indian trail toward the east looking for ponies, and they discovered the troops coming. One of these boys was killed. The other returned to the camp and gave the alarm, and the camp was thrown in the utmost confusion.3 The Uncpapas were in the upper camp up the river. Soon the soldiers were seen in line of battle with their flags displayed, their staffs being planted in the ground, and then the firing began.4 The soldiers could not be seen, but the smoke of their fire was plain. They were in the point of timber. His [Reno's] troops did not get into the camp among the teepees. They did not advance beyond the timber. He says the soldiers were in the timber but a short time. Iron Hawk was busy from the start arousing the warriors to duty and hurrying them to mount their horses in readiness to defend the camp. These braves were collecting on the flank of the soldiers close to the high bank which borders the river bottom on the west.5 Presently, Crazy Horse, having collected his warriors, made a dash for the soldiers in the timber and ran into them; when the warriors assembling close to the bank saw this movement and heard the yells of Crazy Horse's men they also advanced furiously with great yelling, coming down on the flank.6 The soldiers broke and ran in retreat, the Indians using war clubs as the principal weapon, a few using bows and arrows, most of the execution being by knocking the troopers from their horses, the Indians moving right in among them. [Note: here are descriptions by Arikara scout Young Hawk and Sioux warrior Standing Bear of Crazy Horse's first charge of the battle.] The Uncpapas were the first Indians reached when Reno began his attack. Iron Hawk says the Indians were so thick that Reno's men would have been run over and could not have lasted but a short time if they had stood their ground in the woods. All the Indians said another lot of soldiers are moving down on the other side of the ridge.7 They all made a rush and got across the river. At one end of the attacking Indians was Sitting Bull, and at the other end was Crazy Horse. (He is not sure about Sitting Bull, but thinks he was in the fight. Says there were so many Indians that there was no telling about many things.)8 About 19 Indians were killed. Others were wounded, but how many he does not know. The soldiers were stripped but not mutilated. Thinks Sitting Bull was at one end of the attacking Indians, Crazy Horse at one end, and Iron Hawk was on the side toward the ridge and between the ridge and the river in the attack on Custer.9 They surrounded Custer. Says Custer's men in the beginning shot straight, but later they shot like drunken men, firing into the ground, into the air, wildly in every way. Where Custer fell there were about 20 on horseback and about 30 on foot.10 The Indians pressed and crowded right in around them on Custer Hill; one [soldier] broke through on horseback and got away, [and] Indians followed, [but] Iron Hawk told them to let him go and tell the story; he outstripped them, but he dismounted after riding about three quarters of a mile and shot himself in the forehead. He would have escaped.11 When Custer was retreating toward Custer Hill, Indians followed along picking up arms and revolvers and ammunition and went to using these instead of clubs and bows and arrows. From Custer Hill a lot of soldiers broke and ran toward the river when the Indians pressed in on them, and they were killled in trying to escape.12 Two men on this hill wore buckskin suits; another wore such suit at the other end, which means Calhoun Hill.13 Iron Hawk was wounded in the battle, shot through the body; he showed me the wound, the bullet passing through from one side below the ribs and slanting upwards [it] went nearly through but did not come out on the other side. He did not go over the field after the battle. He knew Rain-in-the-Face and he says he was in the fight. He says the whole nation was in the fight; he seems to argue from this that Rain-in-the-Face was there. Iron Hawk has a silver medal with the image of Pres. Grant on one side and these words: "United States of America. Liberty, Justice and Equality. Let us have Peace." On the reverse side is the open Holy Bible, a globe with the words on opposite side of the globe: "Atlantic Ocean", "Pacific Ocean", a stump, plow rake, hoe, shovel, axe, and these words and figures: "On Earth Peace, Goodwill Toward Men. 1871". The medal is about 2 1/2 inches in diameter and some 3/16 of an inch thick. Iron Hawk says the Indians crossed the river anywhere to confront Custer. The first Indians to reach Custer were about one hundred (100).14 He says Custer did not get anywhere near the river; his nearest approach was about a mile off. It must have been about three fourths of a mile at least.15 [Note: Iron Hawk is incorrect here. Custer's men tried to charge across the Little Bighorn, as numerous eye-witness accounts describe. The reason Iron Hawk didn't understand what happened in this part of the battle is that he -- like most Hunkpapas -- was fighting Reno when Custer tried to charge across the Little Bighorn at Medicine Tail Coulee and White Cow Bull shot an officer on a "sorrel horse with... four white stockings." See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.] He remembers that Keogh and his men were killed near the little ravine.16 Iron Hawk was on the field between the ridge and the river. The foregoing interview was on Sunday, May 13th, in the tent of Archie Sword, son of the brother of Captain George Sword, at Chadron.17 Archie Sword is a son-in-law of Iron Hawk. He is a freight handler at the depot. Iron Hawk's discription of the Custer Battle was in the sign language, graphic in the extreme. He is a large, powerful man, features strong and typical, pleasing face, [and] grave demeaner which gives way to great animation when he reaches interesting discourse. Iron Hawk says that the sun was at the meridian when the Custer battle was all over. He looked at the sun when all were killed. Iron Hawk's language in expressing the time was that the sun was "in the middle" of the sky when he looked up. When the fighting began under Reno, Iron Hawk's gestures indicated it was 8 or 9 o'clock. Richard G. Hardorff's Notes: 1 Iron Hawk was a Hunkpapa Lakota who was born in Montana in 1862. For a lengthier account of the Custer Battle, see his interview in DeMallie, The Sixth Grandfather, pp. 190-93. The Iron Hawk interview is contained in the Ricker Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society, reel 5, tablet 25, pp. 131-42. 2 Iron Hawk makes clear that the great village on the Little Bighorn was erected on June 23, which date was positively confirmed by the Oglala, Knife, who courted his wife in the valley on the 23rd, and he eloped with her on the 24th, the time and romantic interlude firmly implanted on his memory; see B1ish, A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux, p. 197. Some sources suggest that the village may not have been established until June 24, which contradiction is perhaps due to the fact that on the latter date several small bands joined the great encampment; see Hammer, Custer in '76, pp. 198, 201. 3 A clear reference to Deeds and his slaying. 4 This was Major Reno's command of Companies A, M, and G which deployed in skirmish order across the valley near the present Garryowen bend. 5 Iron Hawk's party had collected below the high bank of the dry river channel just north (downstream) of Reno's position in the woods. Eventually, these Indians filtered into the brush behind Reno's line and they may have fired the volley which killed several of Reno's men. See DeMallie, The Sixth Grandfather, p. 182, which contains the recollections of the Oglala, Black Elk, who had followed his older brother to this point. See also Hammer, Custer in '76, p. 223, and Graham, The Custer Myth, pp. 258, 263, which contain the observations by George Herendeen who witnessed this volley at close range. 6 Arriving late at the valley fight, Crazy Horse's presence gave renewed vigor to the Indian attack which drove Reno's disorganized command from the valley floor; see McCreight, Firewater and Forked Tongues, p. 112; DeMallie, The Sixth Grandfather, p. 182. According to Standing Bear, the valor displayed by Crazy Horse during this phase of the battle was spoken of by all the people. 7 The "other lot of soldiers" was Custer's command of five companies. 8 Sitting Bull was a ranked member of the Strong Hearts Society and the spiritual leader of the Hunkpapa Lakotas. He was born on the Grand River near the present town of Bullhead, South Dakota, in 1831, near which location he was killed while resisting arrest on December 15, 1890. For his biography, see Stanley Vestal, Sitting Bull, Champion of the Sioux (Boston, 1932); and also Stanley Vestal, New Sources of Indian History 1850-1891 (Norman, 1934); John M. Carroll, The Arrest and Killing of Sitting Bull: A Documentary (Glendale, 1987). By request of his direct descendants, Sitting Bull's remains were exhumed from the Fort Yates Cemetery, North Dakota, on April 8, 1953, and reinterred that same day near Mobridge, South Dakota. This exhumation released an angry exchange of charges and counter charges between both states regarding the jurisdiction over the remains and the legality of this transfer across state lines, its feud eventually resolved by the federal authorities. For an entertaining volume on this matter, see Robb De Wall, The Saga of Sitting Bull's Bones (Crazy Horse, S.D., 1984). 9 Iron Hawk was positioned near the forks of Deep Ravine, southwest of Custer Hill, where he participated in the final stages of the battle. 10 A body count of the slain on Custer Hill revealed the retrains of ten individuals on the crest, while some thirty-two bodies were found on its southwestern slope. Initially as many as ninety troopers may have occupied this elevation. See, for example, the account by the Cheyenne, Two Moons, who stated that near the end of the battle some forty-five men left the hill in an attempt to reach the woods along the river; see Graham, The Custer Myth, p. 103. The crest of Custer Hill was a nearly level place of some 30 feet in diameter. Six sorrel horses had been slain around its perimeter, the color identifying them as belonging to Company C. General George Custer was found near the southwestern edge of the elevation, behind a horse, his right leg across the body of a soldier, while his back was slumped against the bodies of two others. The latter two were identified as probably being Sergeant John Vickory, the regimental color bearer, who lay with his face up. The second body was identified as that of Chief Trumpeter Henry Voss, who lay across Vickory's head, Voss' face being down. [Note: Hardorff is incorrect here. George Glenn, who was on the Seventh Cavalry burial detail after the battle, said Voss's body was found at the water's edge.] Vickory had his right arm cut off at the shoulder. Some 20 feet back from Custer, toward the east side of this level place, lay the extemely mutilated body of Captain Tom Custer. He was laying on his face, the skull broken and flattened from repeated blows to the head. Lt. William W Cooke, his thighs slashed and one of the black whiskers scalped, was found between two horses, close to Tom. The fourth officer on the crest was Lt. Algernon E. Smith, his body having been riddled with arrows. Of the remaining four enlistees, the names of only two are known -- Privates John Parker and Edward C. Driscoll, both of Company I, whose bodies lay near the eastern edge of the elevation; see Richard G. Hardorff, The Custer Battle Casualties: Burial Exhumations and Reinternients (EI Segundo, 1989), pp. 33-35. 11 Yet another reference to an attempted escape, this one occurring near the end of the battle, from Custer Hill. Although the evidence is at variance, this individual may have been Corporal John Foley of C Company whose body was found on a little elevation along Medicine Tail Coulee, some 300 yards east from the river. See Hammer, Custer in '76, pp. 206, 254; Camp Manuscripts, p. 559, Indiana University Library. 12 For a graphic description of this final phase of the battle, see Iron Hawk's frank interview in DeMallie, The Sixth Grandfather, pp. 191-92, which contains his vivid recollections of the killings in and around Deep Ravine. 13 Having learned the identity of their white adversaries several weeks later, many Indians formed the conclusion that General Custer must have been one of the buckskin clad men slain on the hill. One Indian, Standing Bear, had taken a buckskin jacket from one of the dead men which he gave to his mother, and for many years they supposed it was Custer's jacket. This garment was kept hidden until his mother finally cut it up and disposed of it for fear of being caught with incriminating evidence. The Indians' conception of a Custer fully clad in buckskin has been perpetuated through the artistic renditions of many artists. This visualization seemed to have gained acceptance among a number of scholars. However, a careful scrutiny of the present evidence seems to suggest the opposite to be true. Custer may have worn a buckskin outfit on June 25, but so did both of his slain brothers, while at least five other officers who fell with him may have worn a buckskin jacket. It is true that a melancholy reflection by Custer's longtime orderly, John Burkman, reveals an image of Custer wearing a white hat, fringed buckskin coat, and a red tie while galloping away at noon, June 25. But sequential evidence about Custer's apparel seems to suggest a different picture. One source of evidence is provided by the Ree Scout, Soldier, who told Walter Camp that Custer took off his buckskin coat and tied it behind his saddle. There can be no doubt that this observation was made hours after Burkman's because it occurred near the lower forks of Reno Creek. The validity of Soldier's statement receives a boost from Lt. Charles A. DeRudio, who attested to having seen both General Custer and Lt. Cook near Reno Hill, the identification made possible through their clothing-a blue shirt and buckskin pants-the only officers to wear such a combination. Moreover, Peter Thompson, a survivor of Company C, gained his last view of Custer north of Reno Hill, and he described Custer as an alert man, dressed in a shirt, buckskin pants tucked in his boots , and buckskin jacket fastened to the rear of his saddle. Although Thompson embellished considerably on his recollections, the essence of this observation does not involve a selfserving matter. We may therefore conclude from these corroborating sources that the clothing pillaged from Custer's body consisted of a blue shirt and fringed buckskin pants, and that the man fully clad in buckskin was either Boston Custer or his brother, Captain Tom; see Graham, The Custer Myth, p. 345; Glendolin D. Wagner, Old Neutriment (New York, 1973), pp. 151, 155; Hammer, Custer in '76, p. 188; Graham, Abstract of the Reno Court of Inquiry, p. 115; and Daniel O. Magnussen,Peter Thompson's Narrative of the Little Bighorn Campaign, 1876 (Glendale, 1974), pp. 145-46. 14 The initial force which blocked Custer's progress at Medicine Tail Ford consisted of some ten to twenty Indians, four of whom were Cheyennes; see Hammer, Custer in '76, p. 207; Grinnell, The Fighting Cheyenne s, pp. 350, 357; Stanley Vestal, Warpath and Council Fire (New York, 1948), p. 245. 15 Although this statement is supported by others, notably the Hunkpapa, Gall, there is opposing and more convincing evidence that some of Custer's men came close enough to the river to fire into and over the teepees on the other side. See, for example, the statement by the Oglala, Foolish Elk, in Hammer, Custer in '76, p. 198, and also that by the Hunkpapa, Good Voiced Elk, in Walter Mason Camp Papers, Item 6, Denver Public Library. For an analysis of the evidence, see Hardorff, Markers, Artifacts and Indian Testimony, pp. 24-28. [Note: Hardorff is incorrect here. Custer's men tried to charge across the Little Bighorn, as numerous eye-witness accounts describe. The reason Iron Hawk didn't understand what happened in this part of the battle is that he -- like most Hunkpapas -- was fighting Reno when Custer tried to charge across the Little Bighorn at Medicine Tail Coulee and White Cow Bull shot an officer on a "sorrel horse with... four white stockings." See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.] 16 As a result of rank seniority, Captain Myles W. Keogh commanded Companies 1, L, and C in the Custer Battle. On June 27, the remains of Captain Keogh and his immediate command-principally I Company and a few men from L and C-were discovered on the eastern slope of Custer Ridge, near the head of a narrow ravine. Keogh's remains were found in an old buffalo wallow. Across his breast lay the body of his trumpeter, John W. Patton, while near him were found Sergeants James Bustard and Frank E. Varden, both of Company I. Keogh's body did not reveal any signs of mutilation. Comtemporary observers concluded that he had been crippled by a gunshot wound which extensively fractured his left knee and leg. Death came later as his trumpeter and non-commissioned staff chose to remain with him to the end. See Walter Camp Manuscripts, pp. 32, 106, Indiana University Library; Richard G. Hardorff, "Captain Keogh's Insurance Policy," Research Review (September, 1977):17. 17 Also known as Hunts the Enemy, Owns Sword was the son of the Oglala, Brave Bear, of the Bad Face Band. Sword later took the Christian name of George. He was an exceptionally brave and intelligent individual whose leadership abilities led to his election to the office of Shirt Wearer in the late 1860s. The fact that his uncle was Chief Red Cloud may have contributed to Sword's political aspirations and success. Sword twice visited Washington as a member of the Oglala delegations, and perhaps as a result of these visits, he became a "progressive" leader at an early age, realizing that acceptance of the ways of the whites was inevitable. An emissary for the U.S. Military, Sword was instrumental in the negotiations in 1877 which led to the surrender of the renowned Crazy Horse. Three years later, he accepted the position of Captain of the Pine Ridge Indian Police, and in this capacity he faithfully served the U.S. Government for many years. His devotion to his office and Indian Agent Valentine McGillycuddy led at times to friction with Chief Red Cloud, especially during the Ghost Dance troubles of the late 1880s. On a humanitarian note, Sword adopted a little girl who was found alive on the frozen battlefield of Wounded Knee in 1890. He died of natural causes near Chadron, Nebraska, the date unknown to me. Lakota Recollections of the Custer Fight: New Sources of Indian - Military History, compiled and edited by Richard G. Hardorff, The Arthur Clark Co., Spokane, WA, 1991, p 64 -70

Although barely a teenager at the time, Iron Hawk fought in both the Battle of the Rosebud and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Here is the account of the Little Bighorn he gave to Eli S. Richter, and another he gave to his friend Black Elk, who observed the battle.

|

||||||||||||

Chadron, Nebraska [May 13] 1907.

Chadron, Nebraska [May 13] 1907.