|

||||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... David Humphreys Miller's

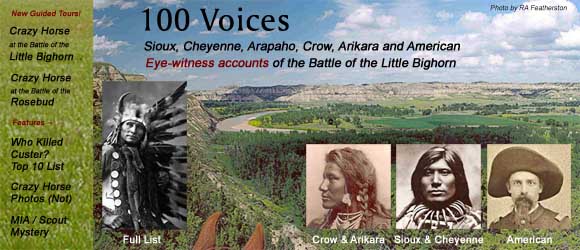

By David Humphreys Miller WHITE COW BULL did not claim to have killed Long Hair (George A. Custer), but to have shot a man, whom he later heard called Long Hair, out of his saddle at the ford. While never mentioned in kill-talks after the battle as Custer's slayer, he (White Cow Bull) may well have been the warrior who inflicted Custer's mortal wound. His story satisfies several enigmas, accounting for the troopers' halt in midcharge and their abrupt shift from offensive attack to defensive and apparently demoralized retreat. Two hundred fifteen hell-for-leather cavalrymen would scarcely have turned back unless they had suddenly found themselves with a dead or mortally wounded leader. The loss of any other officer would hardly have had such a deleterious effect. [Note: See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.] The fact that Custer's body, according to both Indian and white accounts, was later found on the west slope of the ridge to which his troops retreated fails to prove that he was killed or mortally wounded on the spot. Accepting the validity of White Cow Bull's statement that Long Hair fell at the ford actually provides an explanation for the body's location. Only Custer's body would have been carried by the troops as they fell back. In early kill-talks after the battle several other warriors claimed to have slain Long Hair: Red Horse, a Miniconjou; Flat Hip, a Hunkpapa; and Walks-Under-the-Ground, a Santee -- probably because he wound up in possession of Custer's horse. Little Knife, a Hunkpapa, said Brown Back killed Custer to avenge his brother Deeds, who had been killed by soldiers early the day of the fight. Two sons of Inkpaduta (Scarlet Tip), chief of the Santee, made a joint claim. Fast Eagle, an Oglala, said he held Custer's arms while Walking Blanket Woman [Moving Robe], the girl warrior, stabbed Long Hair in the back. Charging Hawk, a Miniconjou, did not deny the deed when others (including Dewey Beard) declared they saw him kill the soldier chief. Three Northern Cheyennes -- Two Moon, Harshay Wolf, and Medicine Bear -- claimed they counted coup on Custer but admitted they did not see him die. Whites were properly confused by this plethora of claims. Such an enterprising showman as Buffalo Bill Cody attempted to credit Sitting Bull -- who turned out to be so affable a showman himself that few believed in his villainy. Eventually as perplexed as white entrepreneurs, poets, and historians, Indian leaders of eleven tribes settled the matter in characteristic fashion -- and to their satisfaction -- in September, 1909, when the wealthy Philadelphian Rodman Wanamaker gathered them in conclave for a last Great Council on the Little Bighorn. He offered a considerable largesse to be prorated among them if one of those present could prove himself to be Custer's killer. After days of deliberation in secret council, mulling over conflicting claims, the chiefs found the record of a sixty-four-year-old Southern Cheyenne war chief made to order: not only had Chief Brave Bear fought at Little Bighorn; he had earlier fought Custer at the Battle of the Washita in 1868, a defeat for his people that provided him with a fitting motive for evening the score. After lengthy palaver the council unanimously elected Brave Bear the honorary slayer of Long Hair Custer! The Battle of the Little Bighorn, on June 25, 1876, has had its impact on history for ninety-five years. Its endless ramifications may well continue to fascinate historians and laymen alike for more generations to come. Undoubtedly, the Custer fight will long remain the apotheosis of the adventurous American spirit... [Note: The following is excerpted from David Humphreys Miller's treatment of this same subject in Custer's Fall...] THE DISPARITY among various Indian versions of the battle made it all the easier for the hero-worshipers to perpetuate the Custer legend. A substitute for Sitting Bull as Custer's slayer turned up unexpectedly at an exhibit of "wild Indians" at Coney Island in the late eighties. Delving into a sullen Sioux warrior's arrest and imprisonment by Tom Custer some fourteen years earlier, writer Kent Thomas got Rain-in-the-Face drunk and with him concocted a cheap publicity story in which the warrior said he had cut out Tom Custer's heart and eaten it. It made fine copy. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow used it as the basis of his epic poem, "The Revenge of Rain-in-the-Face." Taking full dramatic license, Longfellow wrote in part: "'Revenge!' cried Rain-in-the-Face, 'Revenge upon all the race But in the popular concept of the affair, it was Long Hair Custer, rather than his less colorful brother, who was cast as the object of the warrior's vengeance. People across the land accepted Longfellow's verse as historical fact. Later Rain-in-the-Face vigorously denied having killed either of the Custers or having performed such mutilations on their bodies as the poem described. In the dust and turmoil of the battle, he explained emphatically, it had been impossible to distinguish one soldier from another and, like most of the hostiles, he had not known until days later that it was Custer they had been fighting. Nevertheless, the public largely accepted Rain-in-the-Face as Custer's killer. In self-defense Rain-in-the-Face himself finally laid the onus of having killed Custer on Hawk, a young Cheyenne who later accompanied Sitting Bull to Canada and never returned. Few people were convinced, and on his deathbed in 1905 Rain-in-the-Face "confessed" to a missionary, Mary C. Collins, that he thought he had killed Custer, having been "so close to him that the powder from my gun blackened his face." During early kill-talks soon after the Custer battle, various warriors claimed credit for having killed Long Hair. One of them was Red Horse, a Minneconjou. Another was Flat Hip, a Hunkpapa. Another of the same tribe, Little Knife, announced that young Brown Back, brother of the slain boy Deeds, had shot the soldier-chief. The two sons of Inkpaduta (Scarlet Top), chief of the Santees, also asserted they had been in on the kill. Among the Santees, however, the claim of Walks-Under-the-Ground, parading around on Custer's horse, carried more weight. Fast Eagle, an Ogalala, said that he and another warrior had pinioned Custer's arms at the end of the fight while the girl warrior, Walking Blanket Woman [or Moving Robe Woman] (later known as Mary Crawler), stabbed Long Hair in the back. Since Custer's body bore no visible stab wounds, few Indians believed her victim had been the soldier-chief. However, she was afterward permitted to take a man's part in all war dances. Although White Bull [Lazy White Bull]of the Minneconjous never made formal claim to the slaying of Custer, he was convinced until his dying day in 1947 that he had killed Long Hair after the soldier-chief had fired twice at him and missed. Because of his deep misgivings as to what might happen to him, he divulged his belief to only one or two trustworthy whites who kept his secret as long as he lived. The Cheyennes had conflicting ideas on which of their warriors might have slain Custer. Far from being conclusive as to who did the killing, Two Moon, Harshay Wolf, and Medicine Bear each claimed to have counted coup on his body though none of them remembered seeing him fall. For years Indian claimants to the distinction were considerably inhibited by fear. They never knew when rumor alone might bring the Army's swift vengeance. And so, many participants in the battle kept silent, not daring to share secrets with younger, more civilized members of the tribe. Through a confusion of claims, the mysterious identity of Custer's slayer became more obscure than ever. Strangely enough, none of the five warriors who faced Custer at the ford-one of whom almost certainly fired the fatal shot -- ever came forward to say he was the slayer of Long Hair. Long after the Sioux and Cheyennes learned of the remarkable esteem in which Custer had been held by the whites, several warriors insisted they had planned to capture him. Flat Iron, a Cheyenne, stated that such a plot was foiled by Two Moon who had an old grudge against Custer and so killed the soldier-chief before he could be "rescued." Flat Iron blamed the failure on Two Moon's greediness for battle honors. Spotted Rabbit, a Minneconjou, claimed that he had dashed unarmed into the thick of the fighting, hoping to capture Long Hair alive, when his horse had suddenly been shot from under him. Such tales rate little credence since no Indian, as far as is known, recognized Custer or knew he was on the field until after the battle... From "Echoes Of The Little Bighorn" by David Humphreys Miller, American Heritage, June 1971, Volume 22, Issue 4; Custer's Fall: The Indian Side of the Story by David Humphreys Miller, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 1957 p 204 - 206

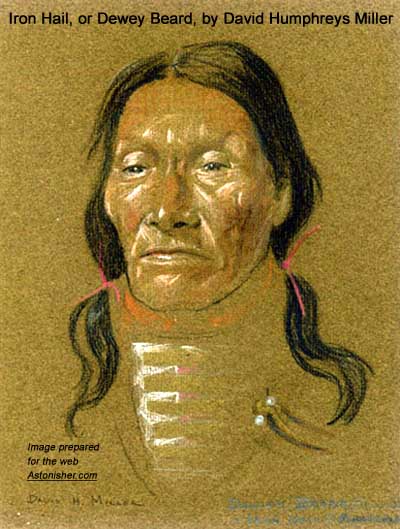

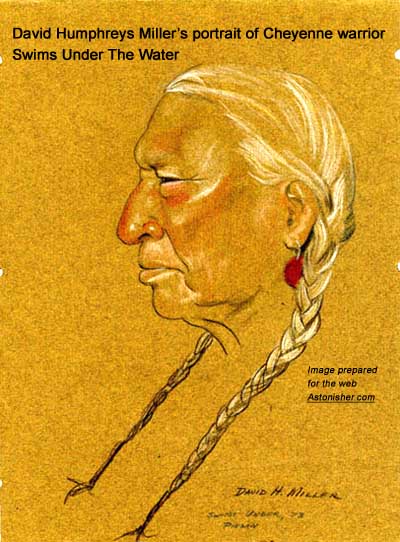

Miller frequenlty made pastel sketches of the Sioux survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn whom he interviewed. Some of Miller's portraits are exceptionally fine evocations of the historic personalities in their own right, such as his portraits of Lazy White Bull and Old Eagle and Black Elk late in life. Click here for information of David Humphreys Miller's sources among the Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Arikara and Apapaho. * * * See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.

|

||||||||||||

Although not born into the Teton Sioux, David Humphreys Miller was adopted late in life by both

Although not born into the Teton Sioux, David Humphreys Miller was adopted late in life by both