|

|||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... John Bourke's Story of the Battle

ON THE BATTLE OF THE ROSEBUD

The Crow scouts with whom I was had gone but a short distance when shots were beard down the valley to the north, followed by the ululation proclaiming from the hill-tops that the enemy was in force and that we were in for a fight. Shot after shot followed on the left, and by the time that two of the Crows reached us, one of them severely wounded and both crying, Sioux ! Sioux!" it was plain that something out of the common was to be expected. There was a strong line of pickets out on the hills on that flank, and this was immediately strengthened by a respectable force of skirmishers to cover the cavalry horses, which were down at the bottom of the amphitheatre through which the Rosebud at that point ran. The Shoshones promptly took position in the hills to the left, and alongside of them were the companies of the Fourth Infantry, under Major A. B. Cain, and one or two of the cavalry companies, dismounted. The Sioux advanced boldly and in overwhelming force, covering the hills to the north, and seemingly confident that our command would prove an easy prey. In one word, the battle of the Rosebud was a trap, and "Crazy Horse," the leader in command here as at the Custer massacre a week later, was satisfied he was going to have everything his own way. He stated afterwards, when he had surrendered to General Crook at the agency, that he had no less than six thousand five hundred men in the fight, and that the first attack was made with fifteen hundred, the others being concealed behind the bluffs and hills. His plan of battle was either to lead detachments in pursuit of his people, and turning quickly cut them to pieces in detail, or draw the whole of Crook's forces down into the canon of the Rosebud, where escape would have been impossible, as it formed a veritable cul de sac, the vertical walls hemming in the sides, the front being closed by a dam and abatis of broken timber which gave a depth of ten feet of water and mud, the rear, of course, to be shut off by thousands of yelling, murderous Sioux and Cbeyenues. That was the Sioux programme as learned that day, or afterwards at the agencies from the surrendered hostiles in the spring of the following year. While this attack was going on on our left and front, a determined demonstration was made by a large body of the enemy on our right and rear, to repel which Colonel Royall, Third Cavalry, was sent with a number of companies, mounted, to charge and drive back. I will restrict my observations to what I saw, as the battle of the Rosebud has been several times described in books and any number of times in the correspondence sent from the command to the journals of those years. The Sioux and Cheyennes, the latter especially, were extremely bold and fierce, and showed a disposition to come up and have it out hand to hand; in all this they were gratified by our troops, both red and white, who were fully as anxious to meet them face to face and see which were the better men. At that part of the line the enemy were disconcerted at a very early hour by the deadly fire of the infantry with their long rifles. As the hostiles advanced at a full run, they saw nothing in their front, and imagined that it would be an easy thing for them to sweep down through the long ravine leading to the amphitheatre, where they could see numbers of our cavalry horses clumped together. They advanced in excellent style, yelling and whooping, and glad of the opportunity of wiping us off the face of the earth. When Cain's men and the detachments of the Second Cavalry which were lying down behind a low range of knolls rose up and delivered a withering fire at less than a hundred and fifty yards, the Sioux turned and fled as fast as "quirt" and heel could persuade their ponies to get out of there. But, in their turn, they re-formed behind a low range not much over three hundred yards distant, and from that position kept up an annoying fire upon our men and horses. Becoming bolder, probably on account of re-enforcements, they again charged, this time upon a weak spot in our lines a little to Cain's left; this second advance was gallantly met by a countercharge of the Shoshones, who, under their chief "Luishaw," took the Sioux and Cheyennes in flank and scattered them before them. I went in with this charge, and was enabled to see how such things were conducted by the American savages, fighting according to their own notions. There was a headlong rush for about two hundred yards, which drove the enemy back in confusion ; then was a sudden halt, and very many of the Shoshones jumped down from their ponies and began firing from the ground ; the others who remained mounted threw themselves alongside of their horses' necks, so that there would be few good marks presented to the aim of the enemy. Then, in response to some signal or cry which, of course, I did not understand, we were off again, this time for good, and right into the midst of the hostiles, who had been halted by a steep hill directly in their front. Why we did not kill more of them than we did was because they were dressed so like our own Crows that even our Shoshones were afraid of mistakes, and in the confusion many of the Sioux and Cheyennes made their way down the face of the bluffs unharmed. From this high point there could be seen on Crook's right and rear a force of cavalry, some mounted, others dismounted, apparently in the clutches of the enemy; that is to say, a body of hostiles was engaging attention in front and at the same time a large mass, numbering not less than five hundred, was getting ready to pounce upon the rear and flank of the unsuspecting Americans. I should not forget to say that while the Shoshones were charging the enemy on one flank, the Crows, led by Major George M. Randall, were briskly attacking them on the other ; the latter movement bad been ordered by Crook in person and executed in such a bold and decisive manner as to convince the enemy that, no matter what their numbers were, our troops and scouts were anxious to come to hand-tohand encounters with them. This was really the turning-point of the Rosebud fight for a number of reasons : the main attack had been met and broken, and we had gained a key-point enabling the holder to survey the whole field and realize the strength and intentions of the enemy. The loss of the Sioux at this place was considerable both in warriors and ponies; we were at one moment close enough to them to hit them with clubs or "coup" sticks, and to inflict considerable damage, but not strong enough to keep them from getting away with their dead and wounded. A number of our own men were also hurt, some of them quite seriously. I may mention a young trumpeter -- Elmer A. Snow, of Company M, Third Cavalry -- who went in on the charge with the Shoshones, one of the few white men with them; he displayed noticeable gallantry, and was desperately wounded in both arms, which were crippled for life ; his escape from the midst of the enemy was a remarkable thing. [Note: Lt. Henry Lemly said Bourke saved Snow's life, but Bourke makes no mention of his own personal heroism.] I did not learn until nightfall that at the same time they made the charge just spoken of; the enemy had also rushed down through a ravine on our left and rear, reaching the spring alongside of which I had been seated with General Crook at the moment the first shots were heard, and where I had jotted down the first lines of the notes from which the above condensed account of the fight has been taken. At that spring they came upon a young Shoshone boy, not yet attained to years of manhood, and shot him through the back and killed him, taking his scalp from the nape of the neck to the forehead, leaving his entire skull ghastly and white. It was the boy's first battle, and when the skirmishing began in earnest he asked permission of his chief to go back to the spring and decorate himself with face-paint, which was already plastered over one cheek, and his medicine song was half done, when he received the fatal shot. Crook sent orders for all troops to fall back until the line should be complete; some of the detachments had ventured out too far, and our extended line was too weak to withstand a determined attack in force. Burt and Burroughs were sent with their companies of the Ninth Infantry to drive back the force which was congregating in the rear of Royall's command, which was the body of troops seen from the hill crest almost surrounded by the foe. Tom Moore with his sharpshooters from the packtrain, and several of the Montana miners who had kept along with the troops for the sake of a row of some kind with the natives, were ordered to get into a shelf of rocks four hundred yards out on our front and pick off as many of the hostile chiefs as possible and also to make the best impression upon the flanks of any charging parties which might attempt to pass on either side of that promontory. Moore worried the Indians so much that they tried to cut off him and his insignificant band. It was one of the ridiculous episodes of the day to watch those, wellmeaning young warriors charging at full speed across the open space commanded by Moore's position; not a shot was fired, and beyond taking an extra chew of tobacco, I do not remember that any of the party did anything to show that he cared a continental whether the enemy came or stayed. When those deadly rifles, sighted by men who had no idea what the word "nerves" meant, belched their storm of lead in among the braves and their ponies, it did not take more than seven seconds for the former to conclude that home, sweet home was a good enough place for them. While the infantry were moving down to close the gap on Royall's right, and Tom Moore was amusing himself in the rocks, Crook ordered Mills with five companies to move out on our right and make a demonstration down stream, intending to get ready for a forward movement with the whole command. Mills moved out promptly, the enemy falling back on all sides and keeping just out of fair range. I went with Mills, having returned from seeing how Tom Moore was getting along, and can recall how deeply impressed we all were by what we then took to be trails made by buffaloes going down stream, but which we afterwards learned had been made by the thousands of ponies belonging to the immense force of the enemy here assembled. We descended into a measly-looking place: a canyon with straight walls of sandstone, having on projecting knobs an occasional scrub pine or cedar; it was the locality where the savages bad planned to entrap the troops, or a large part of them, and wipe them out by closing in upon their rear. At the head of that column rode two men who have since made their mark in far different spheres : John F. Finerty, who has represented, one of the Illinois districts in Congress; and Frederick Schwatka, noted as a bold and successful Arctic explorer. Crook recalled our party from the canyon before we had gone too far, but not before Mills had detected the massing of forces to cut him off. Our return was by another route, across the high hills and rocky places, which would enable us to hold our own against any numbers until assistance came. Crook next ordered an advance of our whole line, and the Sioux fell back and left us in undisputed possession of the field. Our total loss was fifty-seven, killed or wounded-some of the latter only slightly. The heaviest punishment had been inflicted upon the Third Cavalry, in Royall's column, that regiment meeting with a total loss of nine killed and fifteen wounded, while the Second Cavalry had two wounded, and the Fourth Infantry three wounded. In addition to this were the killed and wounded among the scouts, and a number of wounds which the men cared for themselves, as they saw that the medical staff was taxed to the utmost. One of our worst wounded was Colonel Guy V. Henry, Third Cavalry, who was at first believed to have lost both eyes and to have been marked for death; but, thanks to good nursing, a wiry frame, and strong vitality, he has since recovered vision and some part of his former physical powers. The officers who served on Crook's staff that day had close calls, and among others Bubb and Nickerson came very near falling into the hands of the enemy. Colonel Royall's staff officers, Lemly and Foster, were greatly exposed; as were Henry, Vroom, Reynolds, and others of that part of the command. General Crook's horse was shot from under him, and there were few, if any, officers or soldiers, facing the strength of the Sioux and Cheyennes at the Rosebud, who did not have some incident of a personal nature by which to impress the affair upon their memories for the rest of their lives.

We had pursued the enemy for seven miles, and had held the field of battle, without the slightest resistance on the side of the Sioux and Cheyennes. It had been a field of their own choosing, and the attack had been intended as a surprise and, if possible, to lead into an ambuscade also ; but in all they had been frustrated and driven off, and did not attempt to return or to annoy us during the night. As we had nothing but the clothing each wore and the remains of the four days' rations with which we had started, we had no other resource but to make our way back to the wagon trains with the wounded. That night was an unquiet and busy time for everybody. The Shoshones caterwauled and lamented the death of the young warrior whose life had been ended and whose bare skull still gleamed from the side of the spring where he fell. About midnight they buried him, along with our own dead, for whose sepulture a deep trench was dug in the bank of the Rosebud near the water line, the bodies laid in a row, covered with stones, mud, and earth packed down, and a great fire kindled on top and allowed to burn all night. When we broke camp the next morning the entire command marched over the graves, so as to obliterate every trace and prevent prowling savages from exhuming the corpses and scalping them. A rough shelter of boughs and branches had been erected for the wounded, and our medical officers, Hartsuff, Patzki, and Stevens, labored all night; assisted by Lieutenant Schwatka, who had taken a course of lectures at Bellevue Hospital, New York. The Shoshones crept out during the night and cut to pieces the two Sioux bodies within reach ; this was in revenge for their own dead, and because the enemy had cut one of our men to pieces during the fight, in which they made free use of their lances, and of a kind of tomahawk, with a handle eight feet long, which they used on horseback. June 18, 1876, we were turned out of our blankets at three o'clock in the morning, and sat down to eat on the ground a breakfast of hard-tack, coffee, and fried bacon. The sky was an immaculate blue, and the ground was covered with a hard frost, which made every one shiver. The animals had rested, and the wounded were reported by Surgeon Hartsuff to be doing as well "as could be expected." "Travois" were constructed of cottonwood and willow branches, held together by ropes and rawhide, and to care for each of these six men were detailed. As we were moving off, our scouts discerned three or four Sioux riding down to the battle-field, upon reaching which they dismounted, sat down, and bowed their heads; we could not tell through glasses what they were doing, but the Shoshones and Crows said that they were weeping for their dead. They were not fired upon or molested in any way. We pushed up the Rosebud, keeping mainly on its western bank, and doing our best to select a good trail along which the wounded might be dragged with least jolting. Crook wished to keep well to the south so as to get farther into the Big Horn range, and avoid much of the deep water of the streams flowing into Tongue River, which might prove too swift and dangerous for the wounded men in the "travois." In avoiding Scylla, we ran upon Charybdis: we escaped much of the deep water, although not all of it, but enCountered much trouble from the countless ravines and gullies which cut the flanks of the range in every direction. The column halted for an hour at the conical hill, crested with pine, which marks the divide between the Rosebud and the Greasy Grass, a tributary of the Little Big Horn, the spot where our Crow guides claimed that their tribe had whipped and almost exterminated a band of the Blackfeet Sioux. Our horses were allowed to graze until the rear-guard had caught up, with the wounded men under its care. The Crows had a scalp dance, holding aloft on poles and lances the lank, black locks of the Sioux and Cheyennes killed in the fight of the day before, and none killed that very morning. It seems that as the Crows were riding along the trail off to the right of the command, they heard some one calling, "Mini ! Mini!" which is the Dakota term for water; it was a Cheyenne whose eyes had been shot out in the beginning of the battle, and who had crawled to a place of concealment in the rocks, and now hearing the Crows talk as they rode along addressed them in Sioux, thinking them to be the latter. The Crows cut him limb from limb and ripped off his scalp. The rear-guard reported having bad a hard time getting along with the wounded on account of the great number of gullies. already mentioned ; great assistance had been rendered in this severe duty by Sergeant Warfield, Troop 'IF," Third Cavalry, an old Arizona veteran, as well as by Tom Moore and his band of packers. So far as scenery was concerned, the most critical would have been pleased with that section of our national domain, the elysium of the hunter, the home of the bear, the elk, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, and buffalo ; the carcasses of the last-named lined the trail, and the skulls and bones whitened the hill-sides. The march of the day was a little over twenty-two miles, and ended upon one of the tributaries of the Tongue, where we bivouacked and passed the night in some discomfort on account of the excessive cold which drove us from our scanty covering shortly after midnight. The Crows left during the night, promising to resume the campaign with others of their tribe, and to meet us somewhere on the Tongue or Goose Creek. June 19 found us back at our wagon-train, which Major Furey had converted into a fortress, placed on a tongue of land, surrounded on three sides by deep, swift-flowing water, and on the neck by a line of breastworks commanding all approaches. Ropes and chains had been stretched from wheel to wheel, so that even if any of the enemy did succeed in slipping inside stock could not be run out. Furey had not allowed his little garrison to remain inside the intrenchments : he had insisted upon some of them going out daily to scrutinize the country and to hunt for fresh meat ; the carcasses of six buffaloes and three elk attested the execution of his orders. Furey's force consisted of no less than eighty packers and one hundred and ten teamsters, besides sick and disabled left behind. One of his assistants was Mr. John Mott MacMahon, the same man who as a sergeant in the Third Cavalry had been by the side of Lieutenant Gushing at the moment he was killed by the Chiricahua Apaches in Arizona. After caring for the wounded and the animals, every one splashed in the refreshing current; the heat of the afternoon became almost unbearable, the thermometer indicating 103° Fahrenheit. Lemons, limes, lime juice, and citric acid, of each of which there was a small supply, were hunted up and used for making a glass of lemonade for the people in the rustic hospital. On the Border With Crook by John G. Bourke, Charles Scribner's Sons 1891 p 310 - 319

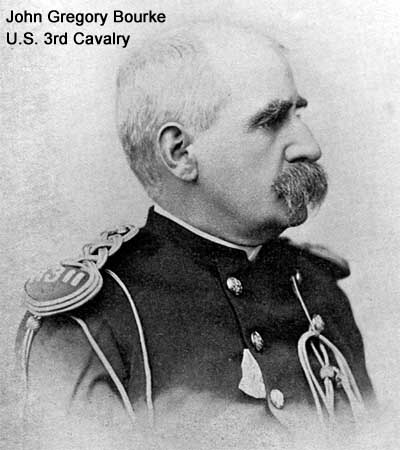

John Gregory Bourke was General George Crook's adjutant.

|

|||||||||||

WE BIVOUACKED on the extreme head-waters of the Rosebud, which was at that point a feeble rivulet of snow water, sweet and palatable enough when the muddy ooze was not stirred up from the bottom. Wood was found in plenty for the slight wants of the command, which made small fires for a few moments to boil coffee, while the animals, pretty well tired out by the day's rough march of nearly forty miles, rolled and rolled again in the matted bunches of succulent pasturage growing at their feet. Our lines were formed in hollow square, animals inside, and each man sleeping with his saddle for a pillow and with arms by his side. Pickets were posted on the bluffs near camp, and, after making what collation we could, sleep was sought at the same moment the black clouds above us had begun to patter down rain. A party of scouts returned late at night, reporting having come across a small gulch in which was a still burning fire of a band of Sioux hunters, who in the precipitancy of their flight had left behind a blanket of India-rubber. We came near having a casualty in the accidental discharge of the revolver of

WE BIVOUACKED on the extreme head-waters of the Rosebud, which was at that point a feeble rivulet of snow water, sweet and palatable enough when the muddy ooze was not stirred up from the bottom. Wood was found in plenty for the slight wants of the command, which made small fires for a few moments to boil coffee, while the animals, pretty well tired out by the day's rough march of nearly forty miles, rolled and rolled again in the matted bunches of succulent pasturage growing at their feet. Our lines were formed in hollow square, animals inside, and each man sleeping with his saddle for a pillow and with arms by his side. Pickets were posted on the bluffs near camp, and, after making what collation we could, sleep was sought at the same moment the black clouds above us had begun to patter down rain. A party of scouts returned late at night, reporting having come across a small gulch in which was a still burning fire of a band of Sioux hunters, who in the precipitancy of their flight had left behind a blanket of India-rubber. We came near having a casualty in the accidental discharge of the revolver of The enemy's loss was never known. Our scouts got thirteen scalps, but the warriors, the moment they were badly wounded, would ride back from the line or be led away by comrades, so that we then believed that their total loss was much more severe. The behavior of Shoshones and Crows was excellent. The chief of the Shoshones appeared to great advantage, mounted on a fiery pony, he himself naked to the waist and wearing one of the gorgeous head-dresses of eagle feathers sweeping far along the ground behind his pony's tail. The Crow chief, "Medicine Crow," looked like a devil in his war-bonnet of feathers, fur, and buffalo horns.

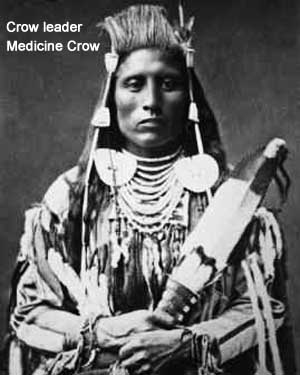

The enemy's loss was never known. Our scouts got thirteen scalps, but the warriors, the moment they were badly wounded, would ride back from the line or be led away by comrades, so that we then believed that their total loss was much more severe. The behavior of Shoshones and Crows was excellent. The chief of the Shoshones appeared to great advantage, mounted on a fiery pony, he himself naked to the waist and wearing one of the gorgeous head-dresses of eagle feathers sweeping far along the ground behind his pony's tail. The Crow chief, "Medicine Crow," looked like a devil in his war-bonnet of feathers, fur, and buffalo horns.