|

||||||||||||

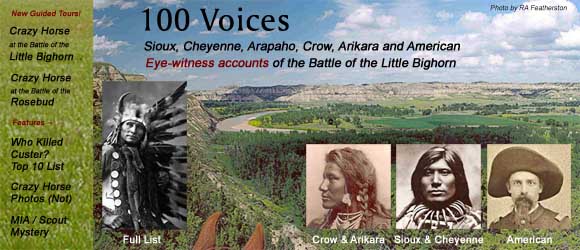

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Frederick Benteen's Story of the Battle

THE LOST IS FOUND CUSTER'S LAST MESSAGE COMES TO LIGHT!

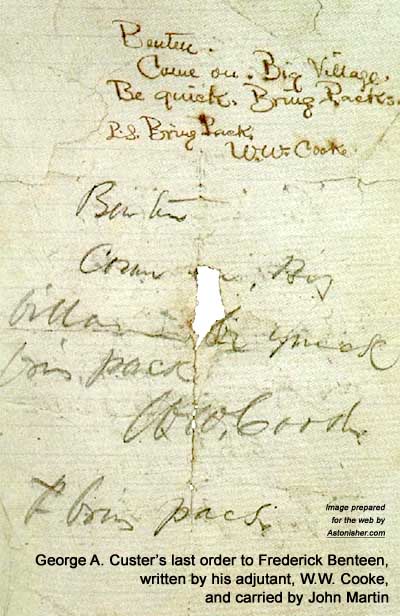

TWENTY YEARS ago this month, after searching for him many months, I found John Martin, the man who carried Custer's last message; the famous message to Benteen that bid him to "come on and be quick" and to "bring the packs." The dispatch of that message marked the crisis of the battle of the Little Bighorn, where Custer, and nearly half the Seventh Cavalry, found death instead of glory waiting for them at the trail's end. Having read avidly all War Department records of this dramatic fight, in which the American Indian achieved his greatest triumph over the American soldier, I keenly wished to write the story of that message. The messenger was found; but the message itself had disappeared. I turned the records inside out in efforts to locate it, until I became a nuisance to The Adjutant General. Then, early in 1923, Major Fred Benteen, son of the gallant officer to whom the message was sent, told me that all his father's papers were destroyed when their home had burned long years before; that the famous message with many another relic of the Little Bighorn had then gone up in smoke. And so I ceased my search, and wrote John Martin's story of how he carried Custer's final message to Benteen. The Cavalry journal published it, with comments by General Edward S. Godfrey, a distinguished participant in the battle, in its July, 1923, number. It now appears that the younger Benteen was mistaken. The message had not gone up in smoke as he supposed, for it has lately become known that after producing it to supplement his testimony before the Court of Inquiry held in 1879 to determine whether Major Reno, Custer's second in command, had been guilty of misconduct at the Little Bighorn, the elder Benteen had presented it to a friend, a certain Captain Price of Philadelphia. Apparently he told no one about it, for Godfrey also believed the paper destroyed by fire. Thus lost since 1879 -- Custer's last message has now been found, and through the commendable efforts of Colonel Charles Francis Bates, Retired, it now rests safe in the library at West Point. The story of its recovery is interesting. For the past fifty years it has been in the possession of the family of a New Jersey collector who acquired it from Price, and who, so far as I can learn, valued it only as a curio. How many other historic documents, I wonder, now accounted for as lost, might be restored to public record if only the collections of relic hunters could be made to give up their secrets? The original message, with other treasures of the collector, was recently advertised for sale at auction. Colonel Bates thus learned of its existence, and arranged with the owner to secure it for West Point. There can be no doubt of its authenticity. Not only is the script of the message itself plainly the hand of Lt. W. W. Cooke, the 7th's regimental adjutant, who died with Custer within an hour of the time he wrote it, but the unmistakable penmanship of Benteen himself, once seen, never forgotten, attests its genuineness in the "translation" made for his friend Price's benefit, and which he inscribed above its pencilled words. It was far from easy to get Martin's story of his ride to Benteen. He was very old and very feeble when I found him deep in the jungle of Brooklyn's Italian quarter. His memory was as feeble as his body, and it was only after I had made three separate visits, each time reading to him (for he was almost blind) his testimony before the Reno Inquiry, that recollection of that fateful June day of 1876 came back. But when it did come back, it came with a wealth of incident and detail that was surprising. And so I wrote his story, just as he told it to me, and he signed it. Between visits to Martin I made an official trip to New Orleans in an attempt to adjust a dispute between the Government and the local "Dock Board" over the title to lands upon which the Army's multi-million dollar warehouses had been built during the World War. Having permission to stop over in Atlanta, I there saw Major Benteen, and it was then he told me that the famous message had been burned: but he told me also that he had some letters written by his father during the campaign of 1876 that had escaped the flames only because his mother had them safely stored away in a fireproof vault. He had never read them, he said, nor shown them to anyone, but he would let me see them; and he did. Two of those letters were written less than ten days after the battle-the first July 2d -- the other July 4, 1876. The letter of July 4th is of especial significance. In it Benteen tells not only of the receipt of Custer's last message, but recounts the harrowing experience through which the regiment had passed; and it tells also all that then was known of what had happened to Custer and his immediate command. But little more has been discovered since. Those two letters Major Benteen permitted me to take back to Washington, where photostatic copies were made. The letter of July 4th, I both showed and read to General Godfrey, saying to him as I did so -- "this letter is of historical importance." The general replied -- "It is far more than that. It was written long before any controversy had arisen over the way the battle was conducted, and under circumstances that give it special credit. It is history itself." Omitting only such parts as are purely personal, here the letter is:

Camp 7th Cavalry, Yellowstone River, Opposite mouth of Bighorn River. My Darling, I will commence this letter by sending a copy of the last lines Cooke ever wrote, which was an order to me to this effect.

McIntosh and Hodgson were killed at Reno's end of line -- in attempting to get back to bluffs. DeRudio [Lt. Charles DeRudio] was supposed to have been lost, but the same night the Indians left their village he came sauntering in dismounted, accompanied by McIntosh's cook. They had hidden away in the woods. He had a thrilling romantic story made out already -- embellished, you bet! The stories of O'Neill [Private Thomas F. O'Neill, the man who was with him] and De R's of course, couldn't be expected to agree, but far more of truth, I am inclined to think, will be found in the narrative of O'Neill; at any rate, it is not at all colored -- as he is a cool, level-headed fellow and tells it plainly and the same way all the time which is a big thing towards convincing one of the truth of a story.

This is a long scrawl -- but not so much in it after all-and I am about getting to the end of my tether. Reno has assumed command and Wallace is Adjutant. Edgerly, Qr. Mr. By the death of our Captains, Nowlan, Bell and Jackson, 3 "coffeecoolers" are made Captains and Godfrey is Senior 1st Lt., Mathey 2d, Gibson, 3d. Quick promotion. I am inclined to think that had McIntosh divested himself of that slow poking way which was his peculiar characteristic, he might have been left in the land of the living. A Crow indian, one of our scouts who got in the village, reported that our men killed a great many of them -- quite as many, if not more, than was killed of ours. The indians during the night got to fighting among themselves and killed each other -- so the Crow said -- he also said as soon as he got possession of a Sioux blanket, not the slightest attention was paid to him. There was among them Cheyennes, Arrapahoes, Kiowa and representatives probably from every Agency on the Mo. River. A host of them there sure. The latest and probably correct account of the battle is that none of Custer's command got into the village at all. We may not be back before winter, think so very strongly. Well -- Wifey, Darling, I think this will do for a letter, so with oceans of love to you and Fred and kisses innumerable, I am devotedly, Your husband FRED BENTEEN. The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania, written and compiled by Colonel W.A. Graham, The Stackpole Co., Harrisburg, PA 1953, p 96 - 97

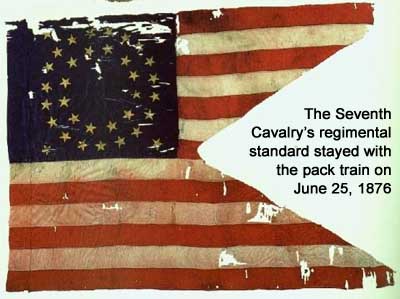

Capt. Frederick Benteen commanded one of Custer's three wings after Custer divided his troops on June 25, 1876. Custer's famous "last order," carried by John Martin, directed Benteen, his best battlefield commander, to "Come on. Big village. Be quick." Benteen was responding to Custer's order when he found Major Marcus Reno -- who led the attack -- and his badly mauled troops fighting for their lives on the east side of the river. Half of Reno's men were already dead or missing, and Reno beseached him, "for God's sake, Benteen, halt your command and wait until I can organize my men." Benteen halted, providing Reno the support that Custer had promised but never provided to the point man on the American attack. White Man Runs Him said Reno's reninforcement by Benteen and McDougall (both of whom had been summoned in Custer's last order) saved all their lives. "If those soldiers [Reno's men] hadn't turned back and been reinforced by the pack train they would all have been killed. The Sioux were coming up fast." After "Wier's company was sent out to communicate with Custer" and was quickly driven back by an "immense body of Indians," Benteen, McDougall and Reno entrenched together in the bluffs above the Little Bighorn, where Benteen's coolness under fire was remarked upon by many during the Seige of the Greasy Grass. William O. Taylor said Benteen was "one of the bravest acting men of our entire command." Here's Private George W. Glenn's account of Benteen exhorting his men along the battle line, and here's Trumpeter John Martin's account of Benteen's quintessentially American response to having the heel of his boot shot off by the Sioux, possibly the Oglala Sioux marksman White Cow Bull, who described a similar incident. Please note: this detail was NOT in Benteen's letter to his wife! Seventh Cavalry surgeon Dr. H.R. Porter spoke for many when he said, "Although Reno was ranking officer, Colonel Benteen was really in command, and to his coolness and bravery those of us who were saved owe our lives." Another quality of Benteen's -- writ as large and plain as his personal bravery and effectiveness as a battlefield commander -- was his hatred of his commanding officer, Col. George A. Custer, whom Benteen had once publically attacked for abandoning his men at the Washita Massacre. "I'm only too proud to say that I despised him," Benteen said of Custer. Yet in the margin of the July 4, 1876 letter to his wife, Benteen scrawled with grief overflowing the normal bounds of the page: ". . . Boston Custer and young Mr. Reed, a nephew of Genl. Custer, were killed, also Kellogg, the reporter..." * * * Here is another account of the battle by Frederick Benteen, as well as his letter to the St. Louis Democrat concerning the Washita Massacre that made George A. Custer so angry.

|

||||||||||||

By Col. W. A. Graham, Retired

By Col. W. A. Graham, Retired July 4th 1876, Montana,

July 4th 1876, Montana,