|

||||||||||||

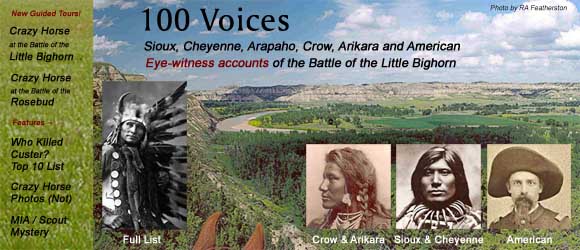

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Drags The Rope's Story of the Battle

DRAGS THE ROPE'S STORY OF THE BATTLE

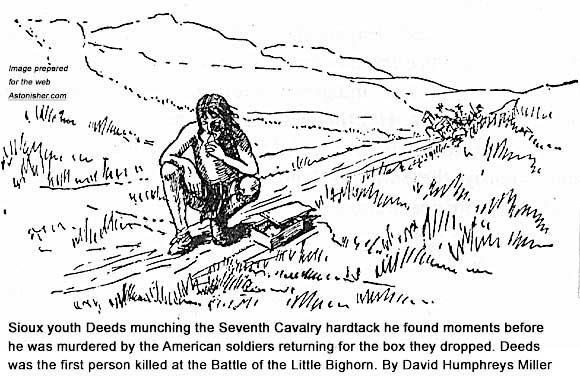

With a moccasined toe, Deeds kicked at clumps of buffalo grass near the Lodgepole Trail, scattering grasshoppers in all directions. Then his foot came against something solid. Looking down, he saw a drab square box -- a container unlike anything used by his people back in the great camp by the river. Such a rare find called for a closer look. The boy hunkered down beside the box. Deeds was barely ten years old. His whole life had been spent deep in the Hunkpapa hunting grounds, far from the white men's spreading settlements. Sparked by a growing boy's naive curiosity, he had not yet learned a warrior's caution. The box had dropped in such a way that the lid had been loosened, yet needed prying to reveal the contents. From the hide sheath hanging against his slim brown flank Deeds took the old skinning knife with the bone handle and went to work. As he pried at the lid, he glanced around, hoping to catch sight of his older brother. Brown Back was still somewhere up the divide, rounding up their grandfather's ponies. As soon as Brown Back came along with the herd, Deeds would pick out a favorite mount and help his brother drive the animals down to the camp. Then their grandfather Four Horns would give away the ponies and all the personal belongings of their grandmother. Deeds still could not believe his grandmother was dead. She had died before dawn that morning, while the drums of the all-night scalp dance still throbbed. It was hard to imagine any camp without his grandmother fleshing hides nearby or carrying in a load of kindling wood or wild turnips, as she had done almost every day as far back as he could remember. Adding to the mystery of death were the solemn words of Deeds's uncle, Sitting Bull, who spoke to the family as they all gathered around the old woman's deathbed. "Her passing means a great event is about to take place," Sitting Bull had announced gravely. "Perhaps my vision of our enemies falling into camp may soon be fulfilled!" The grownups, including the sobbing old Four Horns, had nodded knowingly, while Deeds mutely looked down at all that remained of his grandmother. A little later Brown Back had called him away to help bring in the ponies. The lid came free at last. Inside the box were crumbling slabs of hardtack bread. The boy brought a flake to his nostrils and sniffed. The aroma was not at all like that of the fry bread made by Sioux women. He bit into it, knowing instinctively he was tasting white man's bread for the first time. At the sudden clatter of hoofs on the broken trail, Deeds looked up, expecting to see Brown Back riding toward him with the herd. Still munching hardtack, he turned quickly, realizing the hoofbeats came from behind him. Three white soldiers were riding down on him at a fast gallop, firing their carbines. "He's got the box!" one of them yelled, as shots crashed through the lazy morning stillness. Before Deeds could cry out or run away, a trooper's bullet caught him full in the chest and brought him down. Still afoot, Brown Back came running at the crack of gunfire. An Ogalala youth named Drags-the-Rope followed at his heels. His ponies, too, had strayed up the divide during the long night graze. Now he lent a helping hand to his young Hunkpapa cousins. At a glance he saw he was too late. Deeds lay dead, an ugly wound through his lungs. Without dismounting, the soldiers fired at the older boys as they ran forward. One trooper with stripes on his sleeves seemed to be giving orders to the other two. Dodging the deadly carbine fire, Drags-the-Rope found temporary cover and drew on his training as a warrior's apprentice for a fast decision. Snaking through the grass to where Brown Back crouched cowering and uncertain, he told the Hunkpapa boy to make a run for the village and spread the alarm. "I'll hold off the soldiers until you get away!" Drags-the-Rope shouted. And Brown Back leaped and dodged down the slope like a prongbuck. Once the boy was safely away, Drags-the-Rope pulled at his long nose and grinned. A little victory yell started deep in his throat. His thought now was to recover Deeds's body -- if he could. But with the soldiers reloading and firing continuously, there was no chance of reaching the dead boy. Drags-the-Rope waited until Brown Back was safely out of range, then sprang to his feet and ran a fast zigzag course downhill. If he could reach the distant clump of box elders that marked the head of Medicine Tail Coulee off to the northwest, he could follow the dry wash down to the river and cross directly over into camp. Later, he might guide a small war party back and show them where to find Deeds's body. [Note: Here is Little Soldier's eye-witness account of the Americans murder of Deeds. Cheyenne warrior Dog said another boy, a Ute who had been captured by the Cheyenne, also brought the free Sioux and Cheyenne word that the Americans were approaching that morning.] Ready for anything, he expected at every step to hear the thunder of hoofs behind him. An old Sioux war cry kept echoing in his mind: "This is a good day to die!" But the blue-clad soldiers did not ride him down. And he felt no impact of bullet against his flesh as he ran. Once he was out of range, they stopped firing. He glanced over his shoulder to see all three of them riding on down the Lodgepole Trail, the old Indian route across the Wolf Mountain divide from Rosebud Creek to the Greasy Grass-as the Sioux called the Little Big Horn. If they kept going, they would run head-on into the south end of the great village -- the end where the Hunkpapas were camped. Sensing that more soldiers lurked up on the divide. Drags-the-Rope somehow knew at that moment that these troopers had just fired the first shots of what was destined to be a great battle for Indian and white man alike... Drags-the-Rope reached camp after Brown Back's arrival, having made a wide circle along the divide as far as the headwaters of Tullock's Creek, then cross-country to Medicine Tail Coulee, which he followed down to the ford and across into the village. He told me that, since he could report having seen only three white soldiers, no one in the Ogalala camp seemed at all worried until the alarm went up a few minutes later. He joined Crazy Horse at that time, fighting near the Ogalala leader through most of the battle. Custer's Fall: The Indian Side of the Story by David Humphreys Miller, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 1957 p 3 - 7, 242 - 243

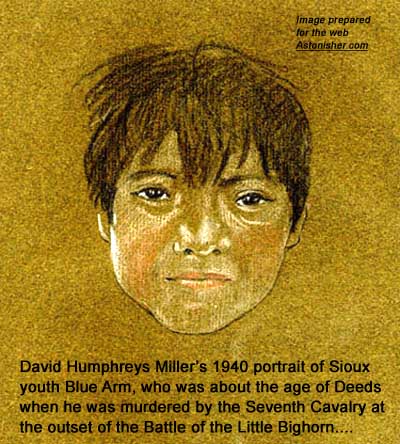

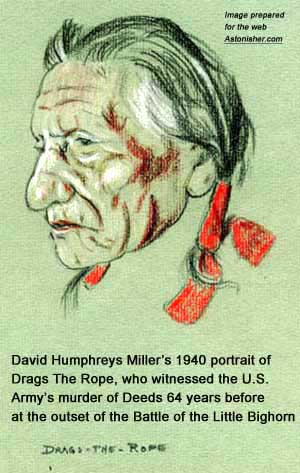

Although based on his memories as a young boy, Drags The Rope's eye-witness account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn is important because it reveals that the first casualty of the battle was a young Sioux boy named Deeds, who was murdered by an American soldier, Quartermaster Sgt. Hearst, as the boy examined a hardtack box that had bounced off one of the Seventh Cavalry's pack animals. Drags The Rope's story further confirms one of the points where fate -- in the form of a hardtack box laying in the dust -- tipped the unfolding saga toward its eventual end that day on the Little Bighorn. According to Seventh Cavalry survivor Daniel Kanipe, Custer ordered his men into a deep ravine on the morning of June 25, apparently intending to remain hidden there for a dawn attack the next day. Sioux warriors Lazy White Bull and Little Soldier, among others, also spoke of the Americans murder of Deeds. But the American soldiers lost a box of hardtack off one of their horses as they trotted into the ravine, and Kanipe said he believed the loss of that hardtack box, the subsequent murder of Deeds when the soldiers went back to retrieve the box, and the escape of Drags The Rope and Brown Back to spread the alarm, tipped the scales and persuaded Custer to attack immediately. The rest is history, as they say. * * * According to David Humphreys Miller, Little Knife identified the Anonymous Boy who he said killed Custer as Brown Back, the older brother of Deeds. See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info. * * * Richard Hardorff mentions some amusing nicknames for Deeds which make him seem like a completely contemporary youth. According to Hardorff, Deeds was also called Brown Ass, Pants, He Is Trouble and Plenty of Trouble. * * * According to Miller, "The story of the killing of Deeds by Sergeant Curtis and his detail was told to me by Drags-the-Rope in 1939, when the old warrior was eighty-one years old. Additional data concerning the death of Four Horns's aged wife was given me by One Bull, Kills Alive, White Bird, and other old-time Hunkpapas." According to the Little Bighorn survivor Daniel Kanipe, the trooper who murdered Deeds was Quartermaster Sgt. Hearst, not Sgt. Curtis. Click here for more American atrocities against Sioux and Cheyenne women and children that day. * * * See Bruce Brown's intro notes to American Horse's account of the battle for a synopsis of what the free Sioux and Cheynne knew from their scouts about Custer's movements before the battle. * * *

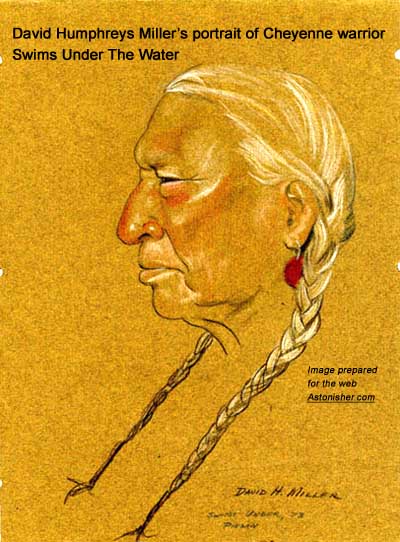

Miller frequenlty made pastel sketches of the Sioux survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn whom he interviewed. Some of Miller's portraits are exceptionally fine evocations of the historic personalities in their own right, such as his portraits of Lazy White Bull and Old Eagle and Black Elk late in life. Click here for information of David Humphreys Miller's sources among the Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Arikara and Apapaho. -- Bruce Brown

|

||||||||||||

Although not born into the Teton Sioux, David Humphreys Miller was adopted late in life by both

Although not born into the Teton Sioux, David Humphreys Miller was adopted late in life by both