|

||||||||||||

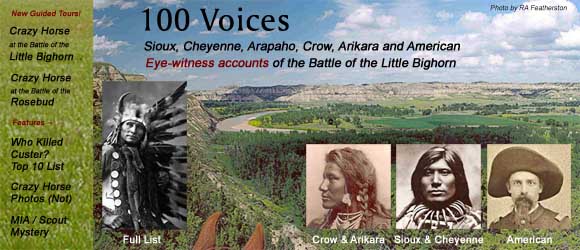

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Thomas F. O'Neill's

THE STORY OF PRIVATE THOMAS F. O'NEILL

"This occupied but a short time, and soon we were again in the saddle. Our scouts were kept busy in front and on the flanks of the column, reporting new signs of Indians. "We were now marching on an Indian trail which was nearly a quarter of a mile wide in some places. Indications were that large bodies of savages had very recently passed in the direction we were going. When we were within about 10 miles of the Little Big Horn River and the Indian camp, Capt. F. W. Benteen was ordered out to the left and front of us with three companies of cavalry. If he saw no Indians after going as far as he thought prudent, he was to rejoin the command. As a matter of fact, he saw no signs of Indians until he got back within sight of the river, just as Reno's men had about finished their charging through to the other side of the stream. "Within three miles or so of the river we came to a place where a small band of Indians had been camped. We evidently surprised them, as they retreated to the larger camp on the river, leaving their cooking utensils on the fires, and one tepee standing. From this point we took the gallop, finally arriving at a high bank over the river. Down the river, on the other side, and about a mile from us, we could see the Indian camp at the edge of a narrow strip of timber or brush, where there were some small cottonwood trees growing. At this point the stream ran close to the high banks. The Indian village was partly concealed from us by a bend in the river. The Indians, however, appeared at the edge of the camp in great numbers, mounted, and running around, apparently greatly excited. "It was at this point that Gen. Custer ordered Major Reno to take his battalion of three troops to the other side of the stream and attack the camp, 'and I will support you,' were the words he used. I belonged to Major Reno's battalion, and we were marched down an old dry creek-bed which debouched into the river near by. Here we crossed the Little Big Horn, the water being about to the horses' bellies. On the opposite bank we formed in fours and took up the gallop toward the Indians. When within about seven hundred yards of them, we came left front into line of battle across the river bottom. When within about five hundred yards of the Indians they opened fire on us. "As the Indians came out in great numbers to oppose us, and moreover as from this point we could see the extent of the village and the immense number of Indians it contained, and how impossible it appeared to be for us -- about 130 or 140 men -- to attempt to charge through such a superior force, our officers decided to act on the defensive. Orders were thereupon given to 'Dismount and prepare to fight on foot.' Three troopers out of each four men dismounted, the fourth man holding the horses. Line was formed, and the horses maneuvered with the line and six or seven yards in the rear of it. "We now began to answer the fire of the Indians, the main body of which seemed to be about a thousand yards away, but great numbers circled about within five hundred yards or less, all mounted and shooting at us. Our right rested near the brush, the left extending about two hundred yards across the plain, the men being three yards apart on the line. At this time, Custer's command was on the opposite side of the river, and the space between the two columns became greater as we advanced. When the fighting commenced, I should judge Custer and Reno were about a mile and a half apart. "General Custer and his five companies now disappeared behind a high bluff, going in the direction of the lower end of the Indian village, and that was the last we ever saw of him or his command alive. "From the point we now occupied we could see the extent of the village. It appeared to be over two miles in length, the tepees covering the river bottom thickly, and the camp in some places was seven or eight hundreds yards wide. "Shortly, the Indians began to close in on our left flank, which was not as well protected. Major Reno evidently realized the danger of being surrounded, or flanked, and wheeled the line, our backs being to the river and our right resting toward the village. It was discovered that at some previous time the stream had run close to our back position, but had changed its course further away about three hundred yards, which left a deep ditch in our rear. We were ordered to lie down on the edge of this bank, keeping up a constant fire, our horses being led behind us. Twenty men under Lieut. McIntosh (of whom I was one) were ordered to deploy in skirmish line and scout the brush, in order to ascertain if the Indians could attack us from the rear. We found thick underbrush and vines and some cottonwood trees growing on this place, and at the head of it and toward the village, a very deep cut or washout. As we discovered no Indians between us and the river, the lieutenant came back and reported. "At this time the fighting was terrific, the Indians charging up very close. They would deliver their fire, wheel their ponies and scamper to the rear to reload. "But we observed that they were forming in greater numbers on our left, where they could deliver a flank fire. It was thought by our officers that they were forming for a charge on that end. A brisk consultation was held by the officers, who shouted back and forth from their positions on the line. It was decided to retreat to a place where they could defend themselves better, as we were losing many men and horses. The order was thereupon given by Major Reno to 'get to your horses, men.' While this order was being given and executed, the fire from the troopers slackened very materially -- in fact, it practically ceased. This gave the Indians greater confidence than ever, and they pressed in on us in greatly increasing num bers. Their forces were greatly augmented by hundreds of others arriving every minute from the lower end of the village. "Reaching our horses the command 'Mount' was given. It was to be a charge to reach the other side of the river. Pistols were drawn by each man, carbines loaded and carried in front of us on the saddles or hanging by our side from the sling-belt, ready for immediate use. "The troopers rode out of the thicket by twos, those on the right being expected to deliver their fire in that direction, and those on the left to attend to that side. It was about three-quarters of a mile across a perfectly level plain before we could reach a fording place. After that, there was a remarkably steep bank to climb to reach the bluffs, and in climbing this, the troops would be fully exposed to a merciless fire. "Every man of our small command seemed to realize fully the desperate situation we were in, and what was expected of him-which was to keep up a constant fire and make every shot tell. "As we emerged from the thicket the warwhoop burst forth from a thousand throats! It was a race for life! The Indians pressed in closely on each side of the column, firing into the troopers, while the troopers in turn answered this fire. It was a hand-to-hand conflict, both Indians and troopers striving to pull each other from their horses, after emptying their weapons, and both succeeding, in a great many instances. I saw six or seven of our men in the act of falling from their horses after being shot. One poor fellow close to me was shot in the body, and as he was falling to the ground, was shot again through the head. I heard the shots as they struck him. "I now found myself in the most desperate situation I had ever faced in my life. Our men were falling; Indians were tumbling from their ponies, either killed or wounded; ponies and horses, riderless, were dashing here and there, rifles, carbines and revolvers were roaring about me, while the cheers of the troopers and the warwhoops of the Indians made everything a perfect pandemonium. "Before I had ridden two hundred yards, my horse crumpled under me, stricken down by an Indian bullet, and I was left dismounted in the midst of the Indians. I saw my comrades leaving me far behind, and expected every minute to feel a bullet, arrow or spear in my body. For a moment I was paralyzed with fear, and did not know what to do. My first thought was to run after the command, and then the folly of such a course became apparent. Then I determined to see if I could not reach the thicket out of which we had just ridden. So I faced about and legged it in that direction, expecting every moment would be my. last on earth. But the Indians seemed all intent on getting at the mounted men, and many of them passed me without seeming to take the least notice of me. Others pointed their guns at me as they swept past on the dead run; some fired at me, but missed. At those who came very close to me, I pointed my carbine. Some would drop to the other side of their mounts, lying nearly flat against the side opposite me, exposing only a foot and part of an arm. At some of these I did fire, but I saw only one fall, although as I was always considered an excellent shot in the regiment, I am sure I must have wounded some whose ponies carried them safely on. "As I reached the thicket and dashed into concealment, I came face to face with Lieut. De Rudio. Like myself, his horse had been shot from under him, and he had had an experience similar to mine in reaching the thicket. The lieutenant was looking intently at the retreating column, doubtless wishing, like myself, that he was with it. I was overjoyed at seeing him, even under such perilous con ditions. Prior to that moment I thought I was the only unfortunate left behind. "The lieutenant then told me that there were two others left behind, like ourselves, and that they were but a few yards from us. It developed that the two men were Billy Jackson, one of our half-breed scouts, and Fred Girard, an interpreter. Lieut. De Rudio got us together and gave us some hurried instructions what to do in case the Indians made a rush on us - which we expected every minute, as we could not possibly hope to escape detection long. "We lay in a hole or indenture in the sand, which I think must have been the river bed at one time. Some thick underbrush growing around this hole pretty effectually concealed us from the view of the savages, who were riding back and forth on the plain in front of our position, and not more than fifty or sixty feet away. They were greatly excited, and reminded me of an ant's nest when disturbed -- everyone seeming intent on something, and everyone on his own business. "The lieutenant instructed us not to fire until discovered - and we expected every second to be. We were lying on our stomachs, with our heads even with the top of the hole, on the lookout for anyone who might approach, and each watching in a different direction, when we would all four fire at them. "The lieutenant kept his keen eyes on all points of the compass, and encouraged us to be cool. `Men,' he said, `we have to die sometime, and we will die like brave men; but I am in hopes we will get out of this scrape yet.' "It was not long before several squaws came around quite close to our position. They picked up their own dead or wounded, their grief seeming most pitiable, wailing and crying. The dead bodies of our men they stripped of their clothing, and cut and multilated them in every conceivable way with the knives which they carried. Some of their actions we could plainly see. It made me faint and sick, not knowing how soon they might be disfiguring my own body in a similar manner, and I determined to sell my life dearly in the event of discovery. Owing to our good position, we figured that we should be able to kill several of our assailants before they could dispose of us. "I did not know what Lieut. De Rudio's own hopes were, but I know that all mine vanished, and I never expected to get out of that place alive. My whole life seemed to pass in a panorama before me, carrying me back to the old home in the East, and to friends whom I had not thought of before in years. All the principal events of my life came crowding forward, one after another, so fast that for a short time I forgot the danger which surrounded me. "An hour passed - two - three, and yet no effort was made to effect our capture, nor were we discovered. In this concealment we lay until darkness over-shadowed the plain in front of us. Then after a whispered consultation we determined to try and find the command-if any of it remained alive, of which we had grave doubts. `Indians never fight in the night time,' the lieutenant confided in a low tone, `and if we keep together and you men will act under my orders, I believe we will yet reach the command alive.' "We had no idea how it had fared with Custer or Reno. We had listened to terrific firing both up and down the river, and realized that the loss must have been heavy. For myself I thought that when the firing had ceased in the direction Custer had gone, it meant that he had retreated to Major Reno's position. I think it was about 5 o'clock when we heard the last shots from Custer's direction; but Major Reno's command kept up their firing at inter vals, as though they were being charged upon. But along about dark, all firing from that direction also ceased. "We talked but little, lest we should be overheard by the Indians. But now we determined to leave our hiding place, although such a move was decidedly precarious, even after darkness had settled down. We looked about and listened intently, but could neither hear nor see anything. The moon was up, and shining through a haze, but it was not very bright, so we decided to make a break for our lives, come what might, as it was our only salvation. We did not dare remain in our present position until daybreak. "Of course we had had nothing to eat or drink. It had been an intensely hot day, and our throats were parched. Perhaps I was more thirsty than the others, owing to the fact that while with the command on the skirmish line, I had caught my foot while maneuvering around, tripping and falling on my nose, which made it bleed profusely. Not being able to give it attention at the time, the blood had run down my throat and almost choked me. It seemed as if I should die of thirst before I could reach water. "When we emerged from the thicket, Girard and Jackson were mounted on ponies they had concealed in the brush. The lieutenant and I were on foot. We advanced but a short distance when a ghastly sight met our eyes. We were on the ground where our command had met the Indians in their retreat. The savages had rushed upon them, killing several of the men, who were lying there, stripped of their clothing, and cut and hacked with the knives of the squaws. We did not pause here many seconds. All the men were beyond any aid from us. We followed along in the trail as well as we could in the uncertain light, the route being well marked by the dead bodies of either troopers or their horses. "We had advanced not more than half way toward the river, when we met - or would have met, had they not sidled off to our right about one hundred yards - a party of mounted savages, eight or ten in number. Lieut. De Rudio and I tried to hide ourselves on the opposite side of the ponies ridden by Girard and Jackson, thinking we might be taken for some of their own people. Evidently the Indians were suspicious, as they ran away from us in the opposite direction-for which, it is needless to say, we were devoutly thankful. "Quickening our pace, we soon reached the river at the point where the command had jumped their horses into the stream in their wild retreat. We scanned the opposite bank for some trace of the spot where they had climbed the precipitous bluff, but could discern nothing but a black, steep bank, towering high. A short distance away there also seemed to be a level piece of flat river-bottom of about fifty yards' extent. "The lieutenant whispered to me to lower myself into the water to ascertain its depth. Holding to some bushes at the edge of the bank, I slid in. I went nearly up to my neck at the first plunge, and the current was so swift it almost swept me off my feet. I climbed hastily out with the assistance of the lieutenant. But he was not satisfied until he had tried it himself. I held him while he slipped into the stream. But he decided it was impossible for us to cross at this place. "It was the first chance we had had of getting a drink of water for many long, weary hours, so I took off my large slouch hat, the crown of which would hold about a gallon, filled it from the stream and passed it around. Each man drank until he was satisfied, and we all declared it was the sweetest water we had ever tasted. "The night was slipping away, and we cautiously explored the bank of the swift-running stream for a ford. Owing to the fact that the melting snows in the mountains at that season of the year sent all streams in that section almost out of banks, it looked like a hazardous undertaking. "In the rear, and down the river, we could see and hear great circles of the Indians holding a war dance around burning piles of wood and brush. The flames lighted the spot about them, and the forms of the Indians could be distinctly seen, jumping about and flourishing weapons. I never will forget the weird appearance of those savages, as their yells and whoops echoed up and down the valley plainly. The only musical accompaniment was a sort of 'Huh-ha, huh-ha!' We afterward learned that they had the heads of three of our comrades, and that these men were partly burned in the fires by these red devils.* It looked as if even the squaws were taking part in the exciting dances. "From the excitement, it was quite apparent to us that the Indians had had a successful day of it. As we had not heard anything further from our comrades since dark, we thought probably they had taken advantage of the night to retreat still further. One thing we did know-our only hope of safety was in getting on the other side of the river. "We continued our march upstream slowly and cautiously, trying in vain to find a fording-spot, but were unsuccessful. We then decided to return to the place where the command had crossed early in the afternoon when making the first attack on the village. "In this conclusion we came to a spot where it seemed likely we could cross the stream. I waded in and found the current less swift, the water reaching but a little above my knees. The others followed, and we crossed what we supposed was the main stream, but we afterward discovered we were on an island. The river divided a short distance above, and ran on each side of this strip of land, which was of considerable extent, being nearly a mile long and several hundred yards wide. It was dotted with thick clumps of bulberry bushes, some of them covering as much as twenty square yards. There were also some young cottonwood trees on this island, and some tall, rank grass which reached to our waists. We crossed the island diagonally, supposing we were really on the other bank, but suddenly we came to the river again. This confused us very much. In riding to the attack in the afternoon we had not observed this island, and we wondered if we might not have become turned around and lost our direction. We tried again to cross the main stream, but it was useless, as we saw nothing on the other side but steep bluffs which we could not possibly climb. "'As we were moving cautiously about, we came to one of these thick clumps of bulberry bushes, and a startled voice suddenly hailed us. The deep, guttural tones were those of an Indian, and Girard and Jackson wheeled their ponies like lightning and galloped away in the direction from which we had approached. That was the last we saw of them until we met them in camp the following night. "Lieut. De Rudio and I were some ten yards apart when the challenge came. I saw him kneeling down in the tall grass, and followed suit as quickly as possible. Had we run away, there was a clear space of nearly a hundred yards which we would have to cross before we could get under cover of one of the brush clumps. The Indians most assuredly would have fired on us. Hearing nothing further after Jackson and Girard galloped away, the Indians evidently thought something was wrong, as they jumped their horses into the river with the greatest haste and confusion. To accelerate their flight, Lieut. De Rudio fired two shots from his revolver in quick succession. I had my carbine pointed in their direction, and I sent a bullet after them. While I was reloading, the lieutenant sent another shot after them. By this time they were across the river. I had not seen any of them, only heard the noise and clatter, but the lieutenant, who was nearer the river, said he could see six or seven Indians, who appeared to be on picket on the point at the fork of the river where it divided to form the island. "As I was about to fire a second shot, De Rudio called out, 'O'Neill, they are all gone.' Possibly the Indians were somewhat drowsy after their hard day's fight, and maybe we caught them napping. I think it must have been about two o'clock at this time. We retreated backward a few hundred yards. From there we wandered about on the island, unable to understand how we were surrounded by water as well as Indians. "After this experience we were afraid to go up to the ford of the afternoon, for fear of running into more Indian pickets. After walking back and forth along the main part of the stream, in a vain attempt to find a ford, I became so tired and utterly worn out that I exclaimed, `Lieutenant, please let us sit down. My boots are full of water, and my clothing all dripping, and I want to wring them out.' So we sat down in a clump of brush, and I took off some of my clothes, my boots and stockings. I had just finished wringing my saturated clothing, and began to put them on again, when we were once more startled by the clatter of horse's hoofs and the sound of voices. The morning was dawning on us before we realized it was growing so late. The Indians were coming past in front of us and along the river bank to begin another attack on Reno's command. The lieutenant had pulled on his boots and I was tugging at mine. He arose and looked out. A column of mounted men were passing us about two or three hundred yards away. Calling to me in a low tone, he excitedly said, 'O'Neill, I believe it is the command.' By this time I had -\my boots on and joined De Rudio. I could see horsemen, but in the uncertain gray of approaching dawn I could not distinguish who they were. They were riding in great numbers, and were near enough so we could distinguish the sound of voices only. Some of them had ascended the bluff through a cut or washout in the bank, which heretofore we had not observed. The lieutenant observed one man dressed in a buckskin suit, whom he took to be Capt. Tom Custer, as he had worn such an outfit on this expedition. De Rudio whispered excitedly, `That surely is Tom Custer!' Some of the horsemen were climbing the steep banks on the other side of the river; some were just at the top and could overlook the island we were on. The rider whom we took to be Tom Custer was just going up the cut. I thought it surely was Captain Custer, and was nearly overjoyed at the prospect of soon being with my comrades once more. At the same time, Lieut. De Rudio stepped boldly out on the river bank and shouted, 'Hey! Tom Custer ! Tom Custer !' The riders stopped and looked in our direction, and then in an instant the warwhoop sounded and a volley of at least fifty shots were fired at us! How we escaped being hit is a miracle, for the bullets cut the brush about us in every direction! The riders were all Sioux Indians dressed in some of the uniforms they had takenwe later learned-from Custer's men in the battle the previous afternoon, and were riding Seventh Cavalry horses which they had captured. "Our escape on this occasion was simply miraculous! None of the Indians made any attempt to cross the river after us. We jumped into the bushes on the opposite side from where we had been standing, and stooping low, ran toward another clump, bending over so that only our backs could be seen above the grass. In this way we reached another thick clump of brush, and just as we were going around it we ran plump into another party of mounted Indians! In fact, we were so close that we almost ran over each other. There were six or seven Indians in the party, and our sudden appearance took them by surprise and frightened their ponies to such an extent that the animals all reared and began to plunge about. Evidently this party was not looking for us in that direction, although some of the savages on the hill were shouting to their companions down below, doubtless warning them to be on the lookout for us. "I had my carbine at a ready. The lieutenant had carried his pistol in his hand for hours, and he immediately opened fire. I also commenced shooting at them. The Indian ponies were rearing, snorting and plunging about to such an extent that their riders had all they could do to stay on the backs of their animals without using their guns. And to this we owed our lives. While they were in this confusion we poured eight shots into them. Two of the riders, I am sure, fell, and I saw three ponies gallop away riderless. I think we must have wounded others who managed 'to cling to their ponies. "This was. a most one-sided encounter. We had the advantage of being on the ground and could deliver a rapid and effective fire. We stood shoulder to shoulder. I did not even throw my carbine to my shoulder-the Indians were so close-but just pointed it in their direction and pulled the trigger. Though I scarcely expected to remain alive five minutes longer, I felt the greatest satisfaction at having inflicted so much injury to the enemy in the short space of time allowed us. I have often wondered if those Indians who did manage to get out of range alive did not consider us two demons whom they ran against in the gray of that June morning, to inflict so much damage among them in such a short space of time. The lieutenant was a quick and accurate revolver shot. He fired five shots, and I am sure he hit the mark every time, while I fired three shots with my carbine. The Indians only fired a single shot at us, which went wild of the mark. De Rudio then shouted to me to run. The last thing I saw of those Indians, two or three of them were on the ground, and several ponies were rearing over each other. "In our flight, and about a hundred and fifty yards from the spot of this last encounter, we came to a place of all places on the little island which was an ideal spot to make a defense and have the advantage of covering. Some time previously, several cottonwood trees had been cut down at this particular point, leaving stumps about three feet high. A freshet had later occurred, washing many fallen logs against these stumps, and there they had remained, forming a small angle, and making a perfect breastwork from which to fire. Lieut. De Rudio's quick eye caught the place, and he exclaimed, 'Quick, O'Neill, get in!" He jumped in among the fallen logs and I after him. We wormed our way still deeper into the mass of debris, and found that we were perfectly protected by the logs. Before any Indians could get at us, it would be necessary for them to cross an open space of nearly one hundred yards, and besides, would have to climb over our barricade to reach us. "We here shook hands with each other, declaring we could not run a step further. If we had to die - as it certainly seemed - we would die there fighting. I took off my cartridge belt, and found that I had just twenty-five rounds left for the carbine and twelve for the pistol. As the lieutenant was the better pistol shot, I gave him mine in addition to his own, and the ammunition for them, while I retained the carbine. "About the time we landed in this retreat, we heard fierce musketry on the hills, apparently about a mile distant. The Indians had again attacked Reno's command. We could hear our comrades responding beautifully. We could also hear the Indian chiefs calling to their men down in the river bottom. Several shots were fired in our direction, but we laid low and did not respond. "All this time we were momentarily expecting the Indians to make a rush on us, and we were looking in every direction for them. The ground behind us sloped down to the river, which was about two hundred yards away, and there was a clear space all about us of nearly a hundred yards. The grass was tall, and we kept a sharp lookout, lest some of the Indians crawl up on our position. We figured that in the event of a charge, we ought to be able to kill five or six of them anyway. I do not think they knew exactly where we were, although several of their bullets struck the logs behind which we were lying. Occasionally we could see them by twos, threes and fives, but not any closer than two hundred and fifty yards at any time; so we laid low and never fired a shot because we did not care to draw their fire. The lieutenant cautioned me `When they come to the clearing, and seem to be looking for us, you take dead aim at the foremost, and then keep up the fire while they are coming toward us, but don't shoot until you are dead-sure of your aim.' At target practice I could hit an object the size of my hat nearly every time at two hundred yards. I was nervous no longer. I had become so desperate that it seemed to quiet my nerves, and I am sure I was as steady as at any time in my life and could do as good shooting. We scarcely expected to get out of this place alive, but it seemed our duty, so the lieutenant said, to defend ourselves as long as possible, and to the best of our ability. There was no use surrendering, as it only meant death by the most horrible form of torture. "About this time a second charge was made against the troops on the hill, and again the Indians were repulsed. Then a desultory firing was kept up by the savages. As we later learned, the Indians picked off a great many men during the intervals between the charges. "'It was now about 9 o'clock in the morning of the 26th, and we were wondering how long the Indians were going to delay the time when they would come to hunt us out. We conversed in a low tone. The lieutenant said, 'O'Neill, I believe they are afraid to come after us; they do not know exactly where we are, and they know they will lose more than they can get. That lesson we taught them a while ago may be our salvation.' "Then De Rudio added, 'O'Neill, are you married?' "'No, sir,' I replied. "'Well,' was the response, `I would not care so much if I were alone, but what will my wife and three young children do if I get killed? That's what is worrying me.' "About this time we heard the sound of voices and the tramp of horses close at hand. Looking cautiously out, we could see great bands of the squaws and children passing on the bottom, up the river, toward the mountains. The squaws were riding like the men, carrying their babies on their backs. Children six years of age and upward rode ponies, and all such were mounted. Their cooking utensils and provisions were all packed on travois. Other ponies were being led or were driven along. We were glad we were not lying where they could see us as they passed. The squaws seemed quite merry, as they were singing and `ke-ing', laughing and shouting to each other. I judge that it took them an hour or more to pass. Sometimes there were bunches of them a couple of hundred yards wide. They did not march in any regular order. Finally it appeared that all had passed us. "Although we could not now see an Indian any place, yet we knew they were on the bluffs over us, as an occasional charge was made on the command. Our hopes now began to revive considerably. We trusted that the command would be able to drive them away, not realizing how badly the troops had been crippled, and how they had to act on the defensive. "One hour after another gradually wore away, until it became about 3 o'clock in the afternoon. I think it was about that time the Indians made the last charge against the command, and it seemed to be a most desperate one and more fierce than any preceding it, judging by the musketry fire and the whooping and yelling on the part of the Indians and the cheers from the troopers. We later learned that the position held by Reno was on top of the highest bluff, while the ground sloped gradually away, with several washouts or deep cuts running in all directions from it. The troopers were formed in line all around the top of this bluff, and in order to reach them, the Indians were obliged to climb the steep sides. In the last charge, some of the savages managed to gain the top of the bluff before they were killed. The troops counter-charged them, and the loss among the Indians was so severe that they made no further attempts to gain the bluff. Had they once broken the line, not a man would have been left to tell the tale. "By 5 o'clock the shooting seemed to have entirely ceased. Neither could we see any further signs of Indians. I finally asked the lieutenant if I might crawl out and take a look around. He told me to do so, and I crawled out to make a little reconnoiter. On the high bank on the other side of the river I saw one solitary Indian, mounted, seemingly on picket. I now moved to a spot where there was a little more shrubbery growing and very cautiously stood up for a look. On our side of the river, and only about three hundred yards from us, I counted fifteen Indians sitting in a circle, seemingly smok ing and talking among themselves. They were near the bank of the main channel of the river. After a glance about I stooped down, and carefully and slowly crawled back to the lieutenant and reported what I had seen. "We now renewed our vigilance, feeling sure that an organized effort would be made to locate us before the Indians left. As we heard no further shooting, nor any signs from the command, we concluded they had retreated and that the main body of Indians had followed them up, leaving a few to guard the spot where we had last been seen. "Now it was again getting near sundown and darkness would soon be coming on. Our hope of getting away now began to rise again rapidly. I became so nervous that I could not contain myself, and for the first time during the day began to feel afraid. Everything was deathly silent around us. I often imagined I saw the forms of Indians creeping up on us, and was nearly ready to fire as the dusk of night came on. "It was now, as much as at any previous time, that Lieut. De Rudio showed himself to be one of the coolest and bravest men I ever saw. He repeatedly quieted me by his sound advice and reassuring manner, saying, 'O'Neill, I know we will get out of this all right if you will just be patient a little while longer. From our experience last night I am certain the Indians will not shoot at night if we chance to run into them. We now know how to get across the river, and if we do not find the command, we will follow our trail back to the Yellowstone River, traveling at night and hiding by day. We can pick up some scraps to eat in our old camps, or maybe we can shoot a deer or an antelope. I am sure we can reach the Far West (our supply steamer) in five days; but I am in hopes of finding the command on the other. side of the river, and then we will be all right.' "We had had nothing to eat in almost forty hours, and nothing to drink all that hot summer day. Our throats were nearly parched. I did not feel at all hungry, however. Night came on about 9 o'clock, and we then left our snug retreat and crept through the long grass to the water's edge. After looking cautiously about, we waded into the stream and crossed in safety to the other side and climbed up the steep banks. Nothing of life was to be seen or heard; not a sound, except the wind sighing through the rank grass and sagebrush. "We now wrung out our wet clothes and dried ourselves as much as possible. We were, as we thought, about a mile from Reno's supposed posiing up on us, and was nearly ready to fire as the dusk of night came on. "It was now, as much as at any previous time, that Lieut. De Rudio showed himself to be one of the coolest and bravest men I ever saw. He repeatedly quieted me by his sound advice and reassuring manner, saying, 'O'Neill, I know we will get out of this all right if you will just be patient a little while longer. From our experience last night I am certain the Indians will not shoot at night if we chance to run into them. We now know how to get across the river, and if we do not find the command, we will follow our trail back to the Yellowstone River, traveling at night and hiding by day. We can pick up some scraps to eat in our old camps, or maybe we can shoot a deer or an antelope. I am sure we can reach the `Far West' (our supply steamer) in five days; but I am in hopes of finding the command on the other. side of the river, and then we will be all right.' "We had had nothing to eat in almost forty hours, and nothing to drink all that hot summer day. Our throats were nearly parched. I did not feel at all hungry, however. Night came on about 9 o'clock, and we then left our snug retreat and crept through the long grass to the water's edge. After looking cautiously about, we waded into the stream and crossed in safety to the other side and climbed up the steep banks. Nothing of life was to be seen or heard; not a sound, except the wind sighing through the rank grass and sagebrush. "We now wrung out our wet clothes and dried ourselves as much as possible. We were, as we thought, about a mile from Reno's supposed position, and as we did not see any further signs of Indians, we walked along in that direction. Occasionally we would lay down and listen, but could hear nothing. The great valley seemed absolutely deserted. We had thought that if the command still held the place where we supposed it to be, we ought to hear some sign of life, and came to the conclusion at last that the troops must have retreated. "Our next decision was to follow the trail down to the Rosebud, and thence to the Yellowstone. We knew the general direction. We decided to cross the divide as soon as possible to the Rosebud and when daylight came to hide in the brush until night, then resume our march until we came to a place of safety. "We began our march along a dry creek and continued on a mile or so until we came to quite a high knoll looming up in front of us. We then concluded to climb to the top and see if we could locate any campfires anywhere. When we reached the top we looked about in every direction, but no fires were to be seen. We were just about to take up our march, very much disheartened, when we heard a mule braying in the direction Reno's command had held. That was the sweetest music I believe I ever listened to. It luckily changed our plans very materially. We figured that the mule surely must belong to the command, so we concluded to search for them, come what might. It was a dangerous undertaking at best. If we were certain it was our men we could assuredly go up within hailing distance and call to them, but we had not forgotten our thrilling experience of the early morning in hailing strangers, and determined to take no such chances. If we crawled up on the command some picket might see us and shoot us, thinking we were Indians. "We walked some distance further in the direction from which the braying of the mule had come, stopping every few yards to listen. At last we came near enough to hear the sound of voices, but could not distinguish whether they were our men or not. Now our predicament was perilous in the extreme. We crawled along on the ground on our stomachs, hitching along a few- inches at a time, expecting every moment to be detected and shot at. We still heard the sound of voices. Sometimes we would think they were Indians, while again we thought they sounded familiar. At last we heard someone exclaim in a loud voice, `Bring that horse here!' I recognized the voice of Sergeant McVey of A Troop, whereupon I called out to him. `Mac, don't shoot on us! It is O'Neill and Lieut. De Rudio !' Several voices thereupon shouted, `Come on in!' which we did in double-quick time. We were in the hands of our comrades at last! "Needless to say, we had much to relate that night before we snatched a little sleep. We discovered that Jackson and Girard had come into camp but a short time prior to ourselves. It seems that after they had run away and left us, they abandoned their ponies and concealed themselves in some thick brush all the next day. Luckily for them, the Indians did not pass close to them, they being outside the line of march. After dark, like ourselves, they found the camp. Jackson was a half-breed Indian scout -- a very young man, but brave and cool. "The Indians had all retreated that evening up the river toward the mountains. General Terry and his command came up about 11 o'clock the next morning, and it was learned that General Custer and every man of his command had been killed about three miles from our position. "Often when I begin to think of all we went through during those trying thirty-six hours of mental torture there in the river bottom, dodging the Indians, I wonder if it is possible that it all did actually happen, or if it was some terrible nightmare." A Trooper With Custer: And Other Historic Incidents of the Battle of the Little Big Horn by E.A. Brininstool, The Hunter-Trader-Trapper Co., Columbus, OH 1925 p 58 - 89

Pvt. Thomas F. O'Neill's account makes a fascinating counterpoint to Lt. Charles DeRudio's account of the experierence they had together behind Sioux lines after becoming separated from the rest of their commrades in Reno's command during Reno's retreat to the river. Here is another, earlier account by O'Neill.

|

||||||||||||

"WE MARCHED until late on the evening of June 23d, then went into camp for the night. The following day we began the march at 4 a. m., continuing up the Rosebud, and made camp late that evening. About 10 o'clock that night, we received or ders to again saddle up and make a night march. We continued on the trail until 4 a. m., when we halted and made coffee, resuming the march about 6 o'clock. After a few hours we came to the head of the Rosebud. Then we began to cross the divide between the Rosebud and Little Big Horn Rivers. Shortly after this, the command halted. Officers' call was sounded, and all the officers reported to General Custer for instructions.

"WE MARCHED until late on the evening of June 23d, then went into camp for the night. The following day we began the march at 4 a. m., continuing up the Rosebud, and made camp late that evening. About 10 o'clock that night, we received or ders to again saddle up and make a night march. We continued on the trail until 4 a. m., when we halted and made coffee, resuming the march about 6 o'clock. After a few hours we came to the head of the Rosebud. Then we began to cross the divide between the Rosebud and Little Big Horn Rivers. Shortly after this, the command halted. Officers' call was sounded, and all the officers reported to General Custer for instructions.