|

||||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Holy Rock's Story of the Battle

HOLY ROCK'S ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE

Anyway, the family was just sitting down to breakfast and my grandmother was sitting there getting ready to ladle out the soup bowls when the messenger rode around the camp and told able-bodied warriors to get their horses and prepare themselves for battle. Soldiers were in the area. My father was at that age where he was curious. All of a sudden his hunger disappeared and he was seized with excitement. He ran out of the tipi and saw a line of horsemen along the ridge. In that first sight he saw one of them was carrying something and there was something waving in the breeze. His mother had come out by then and saw what he saw. She told him, "Son, go get the mare that's ground-staked. Bring it towards the river." So my father ran toward the west of the camp. Most of their horses were grazing there west and south of the camp. My father's family had this one mare with a little bell, probably a sheep bell, or something around her neck. She was ground -- staked so she could go out only so far, and all the other family horses stayed around her. So he ran after and pulled the rawhide thong loose and threw a couple of loops around her nose and one over her ears. But she was a tall horse, he said, what we would call in Lakota tasunke. It was a white man's horse and built like a white man's horse. It was a tall mare. My dad had a hard time trying to get up on her. By that time firing began. Here's the sound of rifle fire and there's horses running all over disturbed by the sound of the guns, and my father couldn't find anything on which to get up high enough so he could get on the mare's back. He tried climbing her leg like a monkey, but she wouldn't stand still. She began to move around because she was getting upset, too. About that time a bunch of the horses stampeded. As they raced by, the mare jerked the line out of his hand and went with them. There wasn't anything more he could do, so he turned and ran back towards camp. When he ran into the camp circle everybody was gone. He ran to his parents' tipi, but nobody was there. He remembered his mother's advice to go towards the river so he started to run across the camp circle towards the river. He heard something so he turned, and there was a line of men -- some were kneeling and some were standing and they were pointing guns right at him. But he didn't stop. He kept running. As he ran, he could hear the bullets going by like a bunch of angry bees or bees traveling in a swarm. He got close to a clump of small brush, so he threw himself headlong into the brush. Above him it sounded like a hailstorm. They must have all been trying to bring him down. That's the first thing that hit me here and got me mad as a boy. Why did they have to do that? He wasn't a soldier! He wasn't a warrior! That began to establish my feelings in connection with what he went through. [Note: See American Atrocities for more info.] It was just a spontaneous reaction of sympathy, anger, whatever. I began to develop an adverse feeling towards the white man. For warriors it was a different thing. They were the protectors, so it's understandable when they go out to do battle that they are prepared to die if necessary. But for a turn in battle to fall upon children, upon those who aren't old enough to fight or women or even babies. Even in the heat of battle where there is a lot of excitement, even soldiers should be humane. If they see a woman running they shouldn't fire. But I suppose they had their orders. General Sheridan would remind the raw recruits signing up for Indian fighting, 'Always remember that nits grow into lice;' as though we were something detestable to be rid of. It's another thing that brought an adverse feeling in my breast; I have never forgiven Philip Sheridan for those words. But the Army was on a campaign of extermination, and our grandfathers were too active or too able at defending themselves and they were costing the government a lot of money. They were determined to take this land one way or the other. I suppose they figured my father was going to grow into lice, so they tried their best to bring him down. But it just wasn't his day to die. Hundreds of bullets flying and one of them should have had his name on it, but it didn't. He survived… By the time my father hit the river, a lot of the old people were already there. Also women with babies. Little babies had to be quiet even in moments of sudden stress and noise. They were taught to be silent. They were taught that in order for the Lakota people to survive. There were roaming bands of enemy tribes and military forces and other groups that sometimes attacked Indian camps for no reason at all. Little babies wrapped up learned to make no noise. They might whimper a little, but then their mothers would shush them. All they would have to say is "shh" or "lece, ah, ah," and the little baby would stop crying immediately and lay there and listen. Children were taught from the ground up to have a sense of survival. My father found his mother and they stayed with the children and the women and the old men and the infirm huddled down in the brush. They could hear the horses, the sounds of bullets, hoofs striking the ground, the rattle of gunfire, and the shouts of men. They knew the battle was engaged, but they didn't actually see much of it because they were all rounded up and taken to a place of safety. My father was down there with the women and the old men when all of a sudden a warrior rode up and here it was an uncle of his. He never told me his uncle's name. My father yelled to him, "Lekse wawan, naopin honiwe, nawana woeuglasotape." "Uncle' he yelled, "they are killing us. We are running out of people. " His uncle heard him and rode over to him and said, "Hala hu tunska anpetu gi le winieasa kte le." "Nephew, you will be a man today." The uncle then grabbed him by the arm and jerked him up and put him on the back of his horse. My father was going to ride to the battle site with his uncle, but his mother hung on to his leg and wouldn't let him go. She had given birth to two children, him and a sister, but his sister died early. Now he was the only one, and his mother didn't want to let him go. She cried and wept, saying he was too young, so his uncle put him down. He used to wonder what would have happened if his mother had not intervened. He might have been killed. His uncle told him that there was a group of soldiers surrounded on the hill, and they were going to make the final run at it. He wanted him to become a man that day at ten or eleven years old. But unfortunately my grandmother intervened and he never got the chance to experience combat. When the battle was over, some historians say that there was a great celebration and dancing. My father said there was no such thing. Many warriors had died, and there were many wounded. Some women and children were killed during Reno's attack. Incidentally, according to my father, when the warriors got mounted they came like a great whirlwind and just enveloped Reno's troops. They ran them through the trees. The cavalry horses and horse handlers were back in the trees, but the warriors' assault was so sudden and swift that a lot of them missed their horses or the horses stampeded. So a lot of the soldiers were on foot. Some of the ones that got mounted had no time to do anything. They were all trying to save themselves because the battle took a turn in favor of the warriors. His uncle told my father that a lot of the soldiers were shouting for their buddies to help them. Some had dropped their guns and now had no weapons. They were hollering at their fellow soldiers, but they were trying to save themselves too. So the warriors rode among them and just clubbed them down. They didn't want to waste bullets, and some didn't have any guns anyway. They managed to corner the rest of the cavalry against the river so they jumped the horses down into the water. He said the banks were high, and as the horses jumped down there some got stuck in the mud and threw their riders. Some were able to get across the river, but the banks were high on the other side and some had to dismount to crawl up the banks… Little Bighorn Remembered -- The Untold Indian Story of Custer's Last Stand, by Herman J. Viola, Times Books, New York, NY 1999, pages 66-72

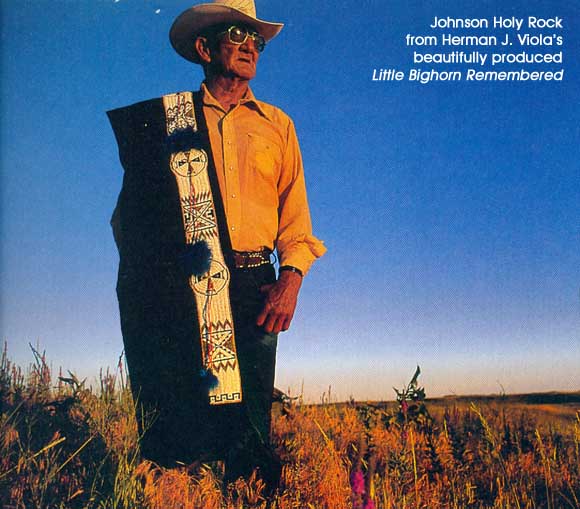

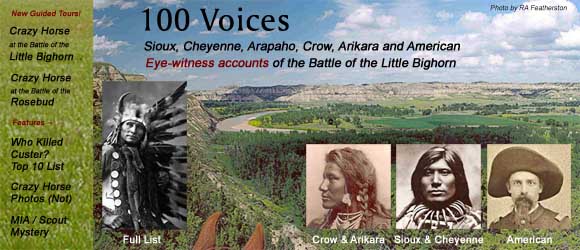

Holy Rock was the son of the reknowned Oglala Sioux warrior White Twin, or Holy Buffalo, whose name appears second on the Crazy Horse Surrender Ledger. Thus two other Sioux notables, Black Twin and No Water (the latter of whom shot Crazy Horse point-blank in the face after Crazy Horse ran off with No Water's wife), were Holy Rock's uncles. Holy Rock's account of his experiences as a child on June 25, 1876 offers a glimpse of the chaotic panic the American Seventh Cavalry's attack initially caused the free Sioux and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn, as well as providing a 19th century example of the all-too-familiar American disregard for the lives of children, woman and the aged who get in the way of the military machine that serves America's imperial ambitions, seen during the 20th and 21st centuries at Kent State, in Viet Nam, and currently in the routine murder of indigenous men, women and children in Iraq, Afghanistan, and most recently by heavy air strikes in the southern desert of Sabha, Libya. The portrait above of Holy Rock's son, Johnson Holy Rock, is from Herman J. Viola's beautifully produced Little Bighorn Remembered -- The Untold Indian Story of Custer's Last Stand. -- B.B.

|

||||||||||||

AT THE TIME of the battle my father was about ten or eleven years old. The camp he was in was the furthest to the south upstream. The others were more to the north and that was the area that Major Reno was assigned to attack…

AT THE TIME of the battle my father was about ten or eleven years old. The camp he was in was the furthest to the south upstream. The others were more to the north and that was the area that Major Reno was assigned to attack…