|

|||||||

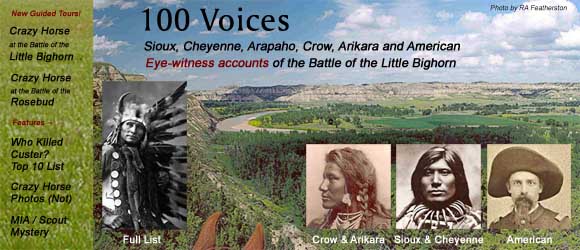

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Charles Windolph's Story of the Battle

SERGEANT CHARLES WINDOLPH'S ACCOUNT

IT WAS AROUND noon on this fatal Sunday of June 25 when we crossed the divide between the Rosebud and the Little Big Horn. We were riding straight west, with the regiment in column of march, the troopers of each company riding four abreast. There was possibly fifty or sixty feet space between companies. Suddenly the column halted, and pretty soon Lieutenant Cooke, who was the regimental adjutant, rode up and I heard him say to Benteen that he was to take his own company "H" and "D," under Captain Weir and Lieutenant Edgerly, and "K" under Lieutenant Godfrey, and bear off to the left and scout the hills that were pitching and bucking as far as you could see. He was to fight anything that he came across and if he saw no Indians on the first ridge he was to keep on going south and west. I didn't know then but I found out later that General Custer kept troops "I," "F," "C," "E" and "L" under his own immediate command. He gave Major Reno a battalion consisting of troops "M," "A" and "G," with most of the Indian scouts under Lieutenants Varnum and Hare. Major Reno also had Charlie Reynolds, Herendon and the interpreter Frank Grouard. Captain McDougall with troop "B" had charge of the rear guard and pack escort. That last was under Lieutenant Mathey, and consisted of six men and a Corporal from each of the twelve troops. That meant that, along with the civilian packers, there were more than 130 armed men in the pack train. Here was the Seventh Cavalry with a total of some 600 men, split up into four outfits. We were Indian hunting in a rolling, mountainous country, far removed from all civilization. We knew that twelve to fifteen miles west of us there was a considerable force of hostiles, but we had little accurate knowledge of how many warriors we would meet, or whether they would run or fight. Apparently the Indian scouts and experienced old guides knew that there were several thousand of the hostiles, but it is my belief that Custer and most of our officers thought they'd have to whip somewhere between a thousand and fifteen hundred. And they expected most of these to be poorly armed and poorly led. From experience they figured the Indians would fight only a rear-guard action, while the women, children, old men and pony herds got away. But in place of a maximum of 1,500 Indian warriors, it developed that there were possibly twice that number about to face Custer's total of 600 or five to one. Apparently Custer had planned to stay in hiding in the ravine we had reached a little after ten o'clock that Sunday, and then attack the village at daybreak on the morning of the 26th. That would more or less have dove-tailed into Terry's idea of boxing the Indians. But when he found the hostile scouts had discovered his column, he figured there was nothing to do but attack at once before they could vamoose. And in justice to Custer I imagine that when he now sent Benteen and the three troops off to the hills on the southwest, it was sort of a half-hearted attempt to carry out Terry's orders to keep scouting on south of the Indian trail that led from the Rosebud westward to the Little Horn. Anyway, Benteen and his trumpeter led off on the left oblique with our three troops. Pretty soon Benteen called Lieutenant Gibson, who was in temporary charge of my own troop, "H," and told him to take a man or two and scout on ahead. Benteen was riding maybe a hundred yards or so in front of the battalion, while Lieutenant Gibson now rode a quarter mile or so on ahead of him. It was rough, rolling country we were going over, and it was hard on the horses. Lieutenant Gibson kept signaling back from each successive hilltop that he could see no signs of Indians. Even to the troopers in the ranks, it looked as if we were on a wild-goose chase. And it wasn't long before we were bearing off to our right, towards the trail Custer and Reno had followed in their march westward towards the Little Big Horn. I suppose we must have been going up and down those rugged hills for the best part of two hours before we turned back on the Custer trail. I think we covered somewhere around seven or eight miles. That doesn't sound very much, until you take into consideration how hard-going it was. I know we were all glad to hit that little valley again. We must have gone two or three miles along the wellmarked trail (shod cavalry horses, you know, cut up the grass so a half-blind man could follow them) when we came to the headwaters of the little stream that flowed on west. Like most places of this nature, it was a sort of morass, and we pulled up and let our horses water in small groups. They hadn't had a drink since late on the previous afternoon. This took a few minutes: then we went on down the tiny creek towards the west. I recall we saw the lead pack mules breaking for the morass just as we were pulling out. Two or three of them got out of control, and were so greedy for water they got stuck in the bog. It showed how slow the pack train was, for here we'd been on this miserable scout over in the hills to the south for a couple of hours and yet we were still ahead of the packs when we reached this spot on the Custer-Reno trail. It's only fair to explain that the mules were not regular pack mules, but animals that had been taken out of the wagon teams. Many of them had been poorly packed, and they had sore backs and were pretty tired. They had gone close to twenty-four hours without water. About the time we were leaving the water hole we began to hear firing way on ahead. Captain Weir lead off his company, although he was second in line of march. But Benteen was at least a hundred yards in advance of him. We all knew we'd be in a fight before long. Shortly after leaving the morass we passed a burning tepee [Note: also known as the Lone Tepee. Custer's scouts set it on fire.]. We figured it had been set on fire by our Indian scouts who were riding with either Custer or Reno. We were trotting briskly now, and there was a good deal of excitement. Horses seem to know when they're heading into trouble the same as men do and some of the mounts were anxious to run away, tired as they were. I figure it was about this time that we saw a trooper coming towards us at the fast trot. I recognized him as Sergeant Kanipe of Tom Custer's "C" troop. He had an order from General Custer for Captain McDougall to hurry across country and bring on the pack mules as fast as he could. He told Benteen what his orders were and the Captain motioned him back down the trail to where the pack train could be found. As Sergeant Kanipe trotted by us, he waved and shouted something about having the Indians on he run. Sergeant Daniel A. Kanipe was born April 15, 1853, at Marion, N. C., and enlisted in Troop C, Seventh U. S. at August 7, 1872. He had barely turned twenty-three at the time of the battle. In Kanipe's own account of the fight, published in the magazine of the Historical Society of Montana [Note: here is another account of the battle by Kanipe.], he says: "Reno and his men went at a swift gallop down Mud Creek across the Little Big Horn River and down the valley toward the south end of the Indian camp. General Custer followed the same route that Reno took, for a short distance, then turned squarely to the right charging up the bluffs on the banks of the Little Big Horn, where he saw a number of Indians... "When we reached the top of the bluffs the Indians had disappeared, but we were in plain view of the Indian camps, which appeared to cover a space of about two miles wide and four miles long on the west side of the river. We were then charging at full speed. "Reno and his troops were again seen to our left, moving at full speed down the valley. At sight of the Indian camps, the boys of our five troops began to cheer. Some of the horses became so excited that their riders were unable to hold them in ranks, and the last words I heard General Custer say were, `Hold your horses in, boys, there are plenty of them down there for us all.' "Custer and his troops were within about one-half mile of the east side of the Indian camps when I received the following message from Captain Thomas Custer, brother of the General: -- 'Go to Captain McDougall. Tell him to bring pack train straight across the country. If any packs come loose, cut them and come on quick-a big Indian camp. If you see Captain Benteen, tell him to come quick-a big Indian camp. "On my route back to Captain McDougall I saw Captain Benteen about half way between where I left General Custer and the pack train. He and his men were watering their horses when first seen. Captain McDougall and the pack train were found about four miles from the Indian camp. The pack train went directly to the bluff where I left Custer's five troops. When we reached there we found Reno with a remnant of his three troops and Benteen with his three troops." -- 2 -- Martini was a salty little Italian who had been a drummer boy with Garibaldi in the fight for Italian independence. Captain Keogh, an Irishman commanding Troop "I," who was riding this day with Custer, had also fought with Garibaldi. I knew Martini very well because he belonged to "H." We used to tease him a lot but we never did after this fight. He proved that he was plenty man. His horse was spouting blood from a bullet wound in his right hip but Martini didn't know anything about it. Benteen ordered him to rejoin his company. I always figured that Benteen thought that since Sergeant Kanipe had already taken word back to Captain McDougall to bring on the pack train as fast as they could come, there was no use sending more word to him. Anyway, Martini's horse was played out and it was all that he could do to keep up with us. Early in 1922, Lieutenant Colonel W. A. Graham, at that time collecting data for his study of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, located the Italian-born Martini in 'Brooklyn, and from the retired trooper obtained his full story. It was published in the U. S. Cavalry Journal in June, 192 3, and since it is an important link in the tragic chain of events most of it is reprinted here: "A little before 8 o'clock on the morning of June 25, my captain, Benteen, called me to him and ordered me to report to General Custer as orderly trumpeter. The regiment was then several miles from the Divide between the Rosebud and the Little Big Horn. We had halted there to make coffee after a night march. "We knew, of course, that plenty of Indians were somewhere near, because we had been going through deserted villages for two days and following a heavy trail from the Rosebud, and on the 24th we had found carcasses of dead buffalo that had been killed and skinned only a short time before. "I reported to the General personally, and he just looked at me and nodded. He was talking to an Indian scout, called Bloody Knife, when I reported, and Bloody Knife was telling him about a big village in the valley, several hundred tepees and about five thousand Sioux. I sat down a little way off and heard the talk. I couldn't understand what the Indian said, but from what the General said in asking questions and his conversation with the interpreter I understood what it was about. "The General was dressed that morning in a blue-gray flannel shirt, buckskin trousers and long boots. He wore a regular company hat. His yellow hair was cut short; not very short-but it was not long and curly on his shoulders like it used to be. "Very soon the General jumped on his horse and rode bareback around the camp, talking to the officers in low tones and telling them what he wanted them to do. By 8:30 the command was ready to march and the scouts went on ahead. We followed slowly, about fifteen minutes later. I rode about two yards back of the General. We moved on at a walk until about two hours later we came to a deep ravine, where we halted. The General left us there and went away with the scouts. I didn't go with him but stayed with the Adjutant. This was when he went up to the `Crow's Nest' on the Divide, to look for the Sioux village that Bloody Knife had told him about. He was gone a long time and when he came back they told him about finding fresh pony tracks close by and that the Sioux had discovered us in the ravine. At once he ordered me to sound officers' call and I did so. This showed that he realized now that we could not surprise the Sioux, and so there was no use to keep quiet any longer. For two days before this there had been no trumpet calls and every precaution had been taken to conceal our march. But now all was changed. "The officers came quickly and they had an earnest conference with the General. None of the men were allowed to come near them, but soon they separated and went back to their companies. "Then we moved on again, and after a while, about noon, crossed the Divide. Pretty soon the General said something to the Adjutant that I could not hear, and pointed off to the left. In a few minutes Captain Benteen, with three troops, left the column and rode off in the direction that the General had pointed. I wondered where they were going because my troop was one of them. "The rest of the regiment rode on, in two columns: Colonel Reno, with three troops, on the left, and the other five troops, under General Custer, on the right. I was riding right behind the General. We followed the course of a little stream that led in the direction of the Little Big Horn River. Reno was on the left bank and we on the right. "All the time, as we rode, scouts were riding in and out, and the General would listen to them and sometimes gallop away a short distance to look around. Sometimes Reno's column was several hundred yards away and sometimes it was close to us, and then the General had motioned with his hat and they crossed over to where we were. "Soon we came to an old tepee that had a dead warrior in it. It was burning. The Indian scouts had set it afire. Just a little off from that there was a little hill, from which Girard, one of the scouts, saw some Indians between us and the river. He called to the General and pointed them out. He said they were running away. The General ordered the Indian scouts to follow them but they refused to go. Then the General motioned to Colonel Reno, and when he rode up the General told the Adjutant to order him to go down and cross the river and attack the Indian village, and that he would support him with the whole regiment. He said he would go down to the other end and drive them, and that he would have Benteen hurry up and attack them in the center. "Reno, with his three troops, left at once on a trot, going toward the river, and we followed for a few hundred yards and then swung to the right, down the river. "We went at a gallop, too. (Just stopped once to water the horses.) The General seemed to be in a big hurry. After we had gone about a mile or two we came to a big hill that "There were no bucks to be seen; all we could see was some squaws and children playing and a few dogs and ponies. The General seemed both surprised and glad, and said the Indians must be in their tents, asleep. "We did not see anything of Reno's column when we were up on the hill. I am sure the General did not see them at all, because he looked all around with his glasses, and all he said was that we had `got them this time.' "He turned in the saddle and took off his hat and waved it so the men of the command, who were halted at the base of the hill, could see him and he shouted to them, `Hurrah, boys, we've got them! We'll finish them up and then go home to our station.' "Then the General and I rode back down to where the troops were, and he talked a minute with the Adjutant, telling him what he had seen. We rode on, pretty fast, until we came to a big ravine that led in the direction of the river, and the General pointed down there and then called me. This was about a mile down the river from where we went up on the hill, and we had been going at a trot and gallop all the way. It must have been about three miles from where we left Reno's trail. "The General said to me, `Orderly, I want you to take a message to Colonel Benteen. Ride as fast as you can and tell him to hurry. Tell him it's a big village and I want him to be quick, and to bring the ammunition packs.' He didn't stop at all when he was telling me this and I just said, `Yes sir,' and checked my horse, when the Adjutant said, `Wait, orderly, I'll give you a message,' and he stopped and wrote it in a big hurry, in a little book, and then tore out the leaf and gave it to me. "And then he told me, `Now, orderly, ride as fast as you can to Colonel Benteen. Take the same trail we came down. If you have time and there is no danger, come back; but otherwise stay with your company..' "My horse was pretty tired, but I started back as fast as I could go. The last I saw of the command they were going down into the ravine. The gray horse troop was in the center and they were galloping. "The Adjutant had told me to follow our trail back, and so in a few minutes I was back on the same hill again where the General and I had looked at the village; but before "Just before I got to the hill I met Boston Custer. He was riding at a run, but when he saw me he checked his horse and shouted, `Where's the General?' and I answered "When I got up on the hill, I looked down and there I saw Reno's battalion in action. It had not been more than ten or fifteen minutes since the General and I were on the hill, and then we had seen no Indians. But now there were lots of them, riding around and shooting at Reno's men, who were dismounted and in skirmish line. I don't know how many Indians there were-a lot of them. I did not have time to stop and watch the fight; I had to get on to Colonel Benteen; but the last I saw of Reno's men they were fighting in the valley and the line was falling back. "Some Indians saw me because right away they commenced shooting at me. Several shots were fired at mefour or five, I think-but I was lucky and did not get hit. My horse was struck in the hip, though I did not know it until later. "It was a very warm day and my horse was hot, and I kept on as fast as I could go. I didn't know where Colonel Benteen was, nor where to look for him, but I knew I had to find him. "I followed our trail back to the place we had watered our horses and looked all around for Colonel Benteen. Pretty soon I saw his command coming. I was riding at a jog trot then. My horse was all in and I was looking everywhere for Colonel Benteen. "As soon as I saw them coming I waved my hat to them and spurred my horse, but he couldn't go any faster. But it was only a few hundred yards before I met Colonel "I saluted and handed the message to Colonel Benteen and then I told him what the General said-that it was a big village and to hurry. He said, `Where's the General "He didn't give me any order to Captain McDougall, who was in command of the rear guard, or to Lieutenant Mathey, who had the packs. I told them so at Chicago in "They gave me another horse and I joined my troop and rode on with them. The pack train was not very far behind them. It was in sight, maybe a mile away and the mules were -- 3 -- But to get back to where I left off. We could hear heavy firing now. Before long we passed several Crow or Ree scouts, driving a few head of Indian ponies, and they shouted "Soldiers," and pointed towards the bluffs that were rising towards the north. We knew that we were close to the valley of the Little Big Horn, and that "somewhere in this neighborhood there was hard fighting going on. Benteen ordered us to draw pistols and we charged up the bluffs at a gallop, expecting at any moment to run into hostiles. When we reached the brow of the first set of rolling hills the river valley suddenly opened up below us to our left. It was a sight to strike terror in the hearts of the bravest men. Down there in the valley maybe 150 feet or more below us, and somewhere around a half mile away, there were figures galloping on horseback, and much shooting. Farther down the river there were great masses of mounted men we suspicioned were Indians. We were going at a fast clip ourselves, and we had no more than caught swift glimpses of this tragic battlefield below, when we saw mounted and dismounted soldiers on the knoll of a hill on to the northward. We rode swiftly towards them. I think I'd better stop long enough right here to tell what happened to our comrades with Reno. Remember it was around 12: 15 noon when Reno was given his three troops and seventeen Crow and Ree scouts and three white scouts. Custer, with his five troops, led off in column on the right, while Reno was on his left. Benteen, with his three troops, had been told to go "valley hunting" in the rough hills over to the south and west. Of course being with Benteen I didn't see anything that happened to either Custer or Reno during the next five hours, but I've heard the story, or stories, so many hundreds of times that I'm going to try to tell it the simplest way I can. But I want it understood that I was not along and that I'm repeating what survivors told me. Custer now motioned Major Reno to cross the little creek they were riding down, and the General instructed his adjutant Cooke to order Reno to cross the Little Big Horn two miles farther on west, and then, swinging to his right, charge the Indian village, and that the whole outfit would support him. That last phrase has been one of the most gnawed-over bones of contention of all the disputed points of the tragedy that was about to happen. . . . Reno led his little group of 120 men and the handful of guides and scouts at a fast trot, crossed the Little Big Horn ford, delaying only long enough to water his thirsty horses and reform in troop formation on the west side of, the river. This west side was a fairly flat valley, possibly a half mile to a mile wide, that led to a low plateau on to the west. On the opposite or east side of the Little Big Horn rose a range of hills one hundred and fifty or more feet high, forming the so-called Wolf Mountains. At several places in these steep cliffs coulees ran down to the river bottom from the bluffs above. The river was, at this time of the year, from a hundred to a hundred and fifty feet wide, running clear and cold, with a gravelly bottom. For almost three miles on the west bank of the river were pitched the various Indian camps. They were strung out and each of the five tribes of the Sioux or Dakotas, the Cheyennes, and small bands of Blackfeet and Arapahoes were camped in their own circles, with possibly as much as a quarter mile separating them. On to the west there were several immense pony herds, guarded by Indian boys and squaws. Altogether there may have been as many as one third of all the Sioux tribesmen here -- possibly close to 10,000 out of 30,000. That would figure out somewhere between 2,000 to 3,000 warriors. And this may be as good a time as any to clear up the popular misconception regarding the arms of the hostiles. It has been generally accepted that all the red warriors were armed with the latest model repeating Winchester rifles and that they had a plentiful supply of ammunition. For my part, I believe that fully half of all the warriors carried only bows and arrows and lances, and that possibly half of the remainder carried odds and ends of old muzzle-loaders and single-shot rifles of various vintages. Probably not more than 25 or 30 per cent of the warriors carried modern repeating rifles. And one other point: Indian boys from fourteen years old up, accompanied the warriors and took part, especially in the latter stages of the fighting. The soldiers, incidentally, were armed with single-shot 45-70 caliber Springfield carbines, an accurate and deadly weapon up to 600 yards. But when fired rapidly the breech became foul and the greasy cartridges often jammed and could not be removed by the extractor. This meant that the empty shell had to be forced out by the blade of a hunting knife. This very fact was responsible for the death of many a trooper this hot Sunday, and may actually have been the indirect cause of the great disaster. Each trooper also carried the latest model six-shot, single-action Colt army pistol. All the soldiers had been ordered to carry 100 rounds of rifle ammunition and twenty four rounds of pistol ammunition, either on their person or in their saddlebags. As the troopers dismounted and each fourth man became a horse holder, many of the horse mounts were stampeded and thus thousands of rounds of much needed ammunition were lost, especially to the men with Custer. There was heavy but wild firing from the Indians ahead, who were being reinforced by hundreds of mounted hostiles. The horses of three of the troopers became unmanageable and dashed straight towards the Indian lines; two troopers, G. H. Meyer and Roman Rutten, managed to circle their horses and, although wounded, join their comrades. The third trooper, G. E. Smith, rode straight to his death. Realizing that his charge towards the Indian hordes would end in almost certain disaster, Reno now ordered his troops to dismount and fight on foot. Even before this order came, scores of Indians had swung to the southwestward and pressed against the Crow and Ree scouts. These were forced to give way. Things were looking bad for Reno, and he ordered his skirmish lines to fall back to the edge of a heavy grove of cottonwoods that followed a bend in the river, and jutted out halfway across the valley. The horses were led into the woods, while the thin line of men held three sides of the grove. Some ninety men were holding not less than 250 yards of line. Hundreds of mounted Indians were now half-circling the skirmish line, riding close in, firing from under their ponies' necks and then galloping away. Reno's men were now either firing from a prone position or were using the bank of a dry creek bed as a barricade and rifle rest. In taking up this new position Sergeant O'Hara of Troop "M" had been killed -- the first man on the skirmish line to die. Apparently Reno had a fairly defendable position and some people think that if he had pulled in his lines, and consolidated his position, he might have held out here for an indefinite length of time-or at least as long as his ammunition lasted. But the savage yells, the heavy firing, the smoke and dust and fear all combined to fog his judgment. Suddenly Custer's favorite scout, Bloody Knife, was shot through the head and his brains scattered over Reno. Then the Negro scout Dorman fell, and soon Charlie Reynolds was shot through the head. Reno, figuring that his only chance lay in getting to high ground across the river, shouted for his men to mount in company formation. Two troop commanders heard the order and amid confusion and excitement had their men mount and line up in column of fours. The third troop, "G," under Lieutenant McIntosh, himself part Indian who had been adopted by General McIntosh, was in the woods and did not get the order until the two other troops, with Reno riding at their head, were racing up stream, trying to find a place to cross the river. All order and discipline were gone. Lieutenant McIntosh, finally getting his troopers in some semblance of a column, pulled out from the woods, far behind the fleeing troops. In the mad rush nineteen men were left behind, including Lieutenant De Rudio and the white scout Herendon. Nobody will ever know how any man escaped alive from this mad retreat. All we are sure of is that the charging troops broke through the cordon of mounted Indians, and followed a buffalo path to the river. Here they somehow managed to jump their horses over a four- or five-foot bank, plunge across the stream, and scramble up a narrow trail in the steep hills to the east. Young Lieutenant Benny Hodgson was shot through the upper leg and his horse killed under him as he jumped him off the west bank of the stream. Grabbing hold of a trooper's stirrup, he was dragged across the river and then cut down by a second bullet, just as he reached the safety of the east bank. In all, twenty-six troopers and scouts and three officers were killed, either in this ride through the Indian gauntlet, or back at the edge of the woods. Of nineteen men left behind, seventeen crossed the river and reached Reno Hill on foot within two hours. Lieutenant De Rudio and Private O'Neill did not join us until thirty-six hours later. They came right through where I was on guard. It was now somewhere around 3:30 in the afternoon. Reno, shaken and unnerved, had reached the hilltop and here his frightened troopers were joining him. He was whipped and completely disorganized. Remember, all this about Reno's fight in the Valley is what I've been told, because I saw none of it with my own eyes. I Fought With Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolf, Last Survivor of the Little Big Horn, as told to Frazier and Robert Hunt, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1947 p. 96 - 107

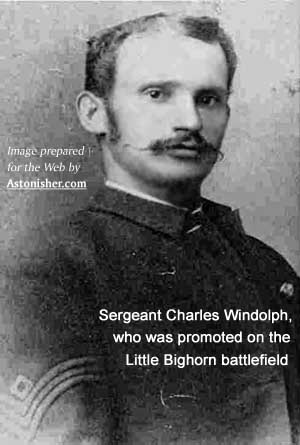

Charles Windolph (sometimes spelled Windolf, especially in later years) was promoted to Sergeant on the Little Bighorn battlefield by Capt. Frederick Benteen, and was subsequently award the Medal of Honor for his valor at the Siege of the Greasy Grass. When this memoir appeared in 1947, he was billed as the last living member of the Seventh Cavalry who fought at the Little Bighorn, so in a way you could say he got the "last word" on the subject. Here is another chapter from Windolf's book, I Fought With Custer. |

|||||||

Chapter 6

Chapter 6