Preface

It is difficult for me to believe any good of myself. Within the oftentimes bombastic and truculent appearance that I present to the world, trembles a heart shy as a wren in the hedgerow or a mouse along the wainscotting.

TO HIS CONTEMPORARIES George Moore was a very great writer. In the 1920's one of the certainties of literary criticism was the view that he was "the greatest living master of English prose." The little circle of partisan champions who gathered around him in his old age in Pimlico of course held this view. But it was no less the opinion of reputed critics outside his cenacle, critics like Rebecca West, whose praise, though reluctant, was hardly less sweeping than that of Moore's disciples. One of his detractors, Ford Madox Ford, said: "When it comes to writing, George Moore was a wolf-lean, silent, infinitely sweet and solitary." Such pronouncements are rarely heard today, for his reputation has emerged only slowly from the long hibernation that commenced with his death in 1933. We have books on Sheridan Le Fanu and Mrs. Gaskell, and French, German, and English publishers issue new biographies of Oscar Wilde with regularity; but, since the publication of Joseph Hone's splendid biography of Moore nearly two decades ago, no study of his work has appeared.

The collapse of Moore's reputation was unquestionably related to the fact that he collected, in the course of a long lifetime, an extraordinary number of distinguished enemies, including Yeats, Hardy, Henry James, Conrad, Middleton Murry, Sir Walter Raleigh, his own cousin Edward Martyn, his own brother, Colonel Maurice Moore, and Whistler, who once "called him out," though Moore was not in a dueling mood and had the good sense to ignore the challenge. In the two decades since his death, the victims of his spleen have nearly all left the stage, carrying the original force of their loathing with them to the grave but leaving behind their testimonials of scorn. To Yeats he was "a man carved out of a turnip"; to Yeats's father he was "an elderly blackguard"; to Middleton Murry, "a yelping terrier"; to Susan Mitchell, "an ugly old soul"; to Ford Madox Ford he was repulsively, inhumanly cold; and even the anonymous authors of Moore's epitaph, carved on a rock on an island in Lough Carra, remind the passing vacationist that for art Moore "deserted his family and his friends."

One can understand these antipathies and may perhaps be moved to extend back through the years a sympathy for those who were driven almost to distraction by the tireless reiteration of Moore's childish, frenzied, and often cruel compulsions. Yet one no longer feels acute distress in the presence of Moore's weaker self. A generation has gone by since his death; the time has passed for composing another of those outbursts that would undertake to scold Moore for being the man he had to be, and for offering with condescension advice about how he might better have invested his talents. Our ambition seeks only to bring to his work the sort of detached curiosity with which he scrutinized it, and to seek the sort of understanding he sought.

|

|

Table of Contents

|

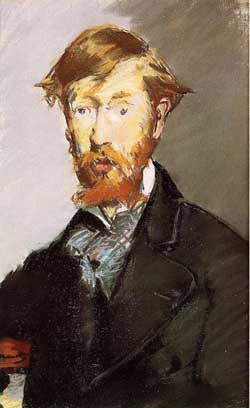

Portrait of George Moore by Eduoard Manet

Astonisher.com is pleased to offer George Moore: A Reconsideration by Malcolm Brown, complete and free for your personal use. (Under construction. More soon!)

Gerore Moore:

A Reconsideration

by Malcolm Brown |

| Preface |

| 1. The Irish Landlord |

| 2. The Parisian |

| 3. First Assault on London |

| 4. Zola's Ricochet |

| 5. Pater's Tide of Honeyed Words |

| 6. Low Life and High Life |

| 7. The Wild Goose Goes Home |

| 8. The White Birds of Recollection |

| 9. The Craftsman as Critic |

| Credits |

University of Washington Professor Malcolm J. Brown (1910 - 1992) with his son, Bruce Brown, in Sumas, WA, July 1988.

|

Additional reading -- Malcolm Brown's The Politics of Irish Literature. Also see Bruce Brown's commentary on The History of the Corporation for Malcolm Brown's contribution to that work. |

|

|

We see him, much as he saw himself, as a stubborn and factminded seeker, torn by violently contradictory impulses, periodically incapable of moderation in discourse. We see him as the most uninhibited, and hence the most valuable, of the commentators to testify upon the motives, satisfactions, frustrations, and persistent, incurable longings of a practicing artist of talent in the opening phase of the modern age, when the ideals to which the artistic world has since given full allegiance were in process of delineation. His story is the story of the painful demise of the Victorian age and the equally painful birth of the age which succeeded. His adventures summarize this entire epoch of transition, and he represents his time rather more fittingly, though with less lurid interest, than Wilde or Beardsley.

One does not hesitate to label him a very important literary figure. His Esther Waters and A Mummer's Wife stand as two of the dozen most perfectly wrought novels to appear in the English realistic tradition since the high noon of Victorian genius, novels not out of place in the company of the best novels of the language. At least six of his other novels seem assured of "permanence." These are A Modern Lover and A Drama in Muslin, which brought the first vivifying transfusion of French realism into the ailing late-Victorian English novel; and The Lake, The Brook Kerith, Heloise and Abelard, and Ulick and Soracha, the novels of his final "melodic line" manner, narratives in which he hoped to bring to the novel the languid, mellifluous flow of mythic streams and the disembodied melancholy of the Celtic twilight. None of these latter novels fits a pattern that is modish just now, and all lie awaiting their eventual rediscovery and resurrection after today's dominant tastes have passed with the mutation of things.

Perhaps his autobiographical writings will carry his fame longest. He found that he was able to study, if not to control, his outrageous personality, and it occurred to him that his own character provided a subject for literary treatment. He set up as his own Boswell and passed the time spying upon himself with mingled affection and malice. He was not, it is true, capable of the sort of candor that Gide has accustomed us to expect. Readers searching Moore's autobiographies for scandals proportionate to his public reputation for wickedness will conclude that he was a very mild sinner after all, being mainly addicted to small petulancies rather than to scarlet flaws. His habit of comparing his confessions to Rousseau's was rather on the boastful side; one is more particularly reminded of Augustine's anticlimax: "And besides that, I stole things from my parents' root cellar and dinner table." Yet one of the most palpable self-portraits of all literature arises out of the pages of his autobiographies and confessionsfirst in Confessions of a Young Man and the anecdotes of Memoirs o f My Dead Life, and later and more impressively in Hail and Farewell, which relates Moore's part in the Irish literary revival and makes the definitive statement of the results to be expected when a fatigued talent, searching for lost innocence, stumbles into a condescending alliance with a mass political and literary resurgence.

It is a commonplace of literary history that Moore held the decisive point in the line of attack against the tyranny of antiquated Victorian ways in art and literature. If Victorian prudery and evangelical priggishness were a dragon to be slain, Moore, as much as any literary figure, deserves to be remembered as the Siegfried who did the deed. As Ruth Zabriskie Temple has shown, he was not only the most knowing critic of living French and continental culture in late-Victorian England but also its most influential publicist, broader and more generous than his illustrious predecessor, Swinburne, and more authoritative and perceptive than his dedicated contemporary and friend, Arthur Symons. He discovered Laforgue before Ezra Pound was born; and a generation before T. S. Eliot made Bloomsbury familiar with Gerard de Nerval's unhappy Prince of Aquitaine of the fallen tower, Moore was quoting with glittering eye the sestet of the same sonnet:

J'ai reve dans la grotte ou page la sirene.

How many readers owe their discovery of Balzac, Flaubert, Zola, Turgenev, Huysmans, Verlaine, Manet, Degas, and even Wagner to the infectiousness of Moore's enthusiasms?

Moore's allegiances were both fanatical and mercurial. He was totally devoid of loyalty to yesterday's absolute and ruthless in casting off ideas and emotions, not to say friends, when they no longer served him. The variety of his aesthetic adventures was unparalleled. Every important literary and artistic circle of late-Victorian and Edwardian times saw him arrive -- and depart.

At one time or another he considered himself to be a preRaphaelite, a "decadent," a symbolist, a naturalist, an Ibsenite, a Wagnerian, a Gaelic Leaguer, an imagist, an impressionist, and at last the creator and sole practitioner of his own late literary manner. He embraced no fewer than seven distinct literary styles and manners. This was the peculiarity that occasioned Oscar Wilde's famous jibe, "Moore conducts his education in public," and that led other contemporaries to mutter angrily about his opportunism and meretriciousness. "He stands for nothing," said his estranged brother Maurice somewhat oversimply. The same trait was applauded by his friends as a "passion for self-renewal." He was the most adventurous of the important artistic figures of his time, and his career was an incomparable aesthetic journey, ranging more widely than the careers of Shaw, or Bennett, or Wells, or even Joyce and Yeats, though he did not always return from his expeditions as enriched as they.

Moore's collected works are of course one's first concern. But these volumes might better have been called "selected," since they were painstakingly sorted and polished in old age to present his best to posterity. Of the thirty-five volumes that Moore took to press during his career, some fifteen volumes were subsequently disowned. Such vigorous culling is unusual, especially since Moore had no Grub Street phase to renounce, but was seemingly a serious writer from first to last. One turns with curiosity to the disowned volumes and finds there other abundant riches. Three of them are essential for understanding Moore, though many commentators have shared Moore's embarrassment in their presence and have tried to put them out of mind. One is Pagan Poems, an attempt to Anglicize the poetry of Baudelaire, notable for a failure whose enormity casts suspicion on Moore's motives. A second is Parnell and His Island, a hysterical anti-Irish pamphlet published at the height of the Home Rule agitation in the late 1880's shortly before the fall of Parnell. The third is Mike Fletcher, a forerunner of the fin de siecle novel, the first exhibit in English fiction of the moods that later flowered in the English decadence of the 1890's. One might perhaps agree that these volumes are without literary merit; yet it is not possible to maintain that they are uninteresting or unimportant.

Such lapses into absurdity make the tasks of the critic delicate and difficult. A reader approaching Moore for the first time is likely to be dismayed by his perversity. He introduces himself as a fool caught in the grip of a compulsion to degrade all good things into noise and vulgarity, and one is impatient to dismiss him as at best no more than amusing and at worst simply unspeakable. Eventually one learns the inadequacy of this first impression and comes to glimpse behind his absurdity a rare and complex talent, gentle, perspicuous, and not without an austere dignity and poise.

Still, his absurdity cannot be laughed off or argued away. Like Rossetti's chloral glass and Gide's cape, it casts its shadow across pages where it is unwanted, distracting the mind from pure consideration of art. Unquestionably Moore was hounded by a frightful inner disharmony, as Charles Morgan pointed out many years ago. His absurd manner was a symptom, though an enigmatical one, puzzling to his friends and contemporaries and obsessing his own endless self-searching meditations.

Among his oddities, Moore possessed an incorrigible taste for bluntness. "I haven't enough talent to be obscure," he once said. Like the French, whom he admired above all other people, he had a way of forcing tendencies to yield up their ultimate polar implications. These he would embrace and flaunt, loudly scornful of the timid straddlers who begged him to remember common sense. This was the peculiarity of his temperament that led Yeats to house him in the same phase of his well-known astrological system with H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw, the three representing for Yeats the absolutely earth-bound antimystical temperament.

But a second look at Moore's "clarity" warns that it was not always as innocent and ingenuous as it sounded, and further scrutiny suggests that he had invented a way of approaching sensitive issues that was sly, intricate, and oblique. What is one to make of a pronouncement like this:

What care I that some millions of wretched Israelites died under Pharaoh's lash or Egypt's sun? It was well that they died that I might have the pyramids to look on, or to fill a musing hour with wonderment. Is there one amongst us who would exchange them for the lives of the ignominious slaves that died?

This is a specimen of a "Moorism," a violent rhetoric of mingled self-assurance and self-mockery peculiar to his vision. In his lifetime it was commonly believed that this mannerism betokened simple crudeness of mind. That it was a kind of excess is clear enough; but its simplicity is illusory, a part of a trick so successfully played that it seems to have disarmed most of his contemporaries. Even Yeats, though an expert on "masks" and the convolutions of irony, was deceived. "Violent and coarse of temper," was the last of his many denigrations of Moore, a man he hated but could not drive from old-age memories and dreams. Yeats's judgment was understandably vehement, since a long history of enmity lay behind it. New readers of Moore are forewarned and should be cautious in inferring behind Moore's peculiar manner either outrageous candor or, on the other hand, ordinary spoofing. More than one scholar, including the present writer, has found himself led into the swamps by failing to be constantly suspicious of Moore's rhetoric.

During the past generation the memoirs of literary and artistic folk in Dublin and London have teemed with anecdotes about Moore. These are an "original source," and in America, at least, they are the principal vessel of his reputation at the present time. They have a certain importance; though, when one collects them all together, one is struck by their repetitiveness and suspects that we have inherited almost too many George Moore anecdotes. Invariably they depict a foolish Moore, and to support this impression they commonly mention his receding chin and white walrus mustache, his female pelvis, his champagne-bottle shoulders (Moore's own phrase, and his china-blue eyes peering icily at his fellow men. Many of the anecdotes deal with his uncontrollable urge to make scenes in public and tell how he would swoop down upon some innocent and unsuspecting waitress, taxi driver, or mere passer-by, pouring out a torrent of unmotivated abuse, a habit that grew more ugly as senility took hold of him. Most of all, the anecdotes deal with his grandiose boasts of sexual adventure, but without creating a clear impression. Some hint broadly that his boasting cloaked a condition of sexual impotence -- hence Susan Mitchell's well-known report that he was a lover who "didn't kiss, but told"; others imply that he was a veritable Priapus strolling the boulevards. The somber, muted artist who stands behind his best creative work does not often appear in the memoirs of his acquaintances.

Malcom Brown

Seattle, Washington

May 6, 1955

"George Moore: A Reconsideration" © Copyright 1955 Malcolm Brown

Also by Malcolm Brown...

|

"Mr. Brown's masterpiece..."

-- Michael Foote in the London Evening Standard

The Politics of Irish Literature

From Thomas Davis to W.B. Yeats

by Malcolm Brown

* Complete book now available on Kindle! |

© Copyright 1973 - 2020 by Bruce Brown and BF Communications Inc.

Astonisher and Astonisher.com are trademarks of BF Communications Inc.

BF Communications Inc.

P.O. Box 393

Sumas, WA 98295 USA

(360) 927-3234

Website by Running Dog  |